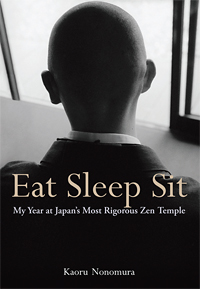

Eat Sleep Sit: My Year At Japan’s Most Rigorous Zen Temple

Kaoru Nonomura

Translated by Juliet Winters Carpenter

Tokyo/New York:

Kodansha International, 2009

328 pp.; $24.95 cloth

Near the end of Kaoru Nonomura’s memoir about his year at Eiheiji, Japan’s elite training temple for Soto Zen priests, his friend Choshu suddenly declares that he is leaving the monastery to attend college. “What made you decide to do that?” Nonomura asks, surprised. But the question seems disingenuous. From the beginning, Nonomura and his fellow trainees are slapped, slugged, kicked, and shoved down flights of stairs. Climbing back up only earns them more kicks and blows from monastery officials, as does virtually any violation of protocol, however minor—even eye contact with a superior. A better question might be, “Why on earth would you stay?”

Near the end of Kaoru Nonomura’s memoir about his year at Eiheiji, Japan’s elite training temple for Soto Zen priests, his friend Choshu suddenly declares that he is leaving the monastery to attend college. “What made you decide to do that?” Nonomura asks, surprised. But the question seems disingenuous. From the beginning, Nonomura and his fellow trainees are slapped, slugged, kicked, and shoved down flights of stairs. Climbing back up only earns them more kicks and blows from monastery officials, as does virtually any violation of protocol, however minor—even eye contact with a superior. A better question might be, “Why on earth would you stay?”

As described by Nonomura, such violence (which also includes sleep and food deprivation so bad that trainees are frequently hospitalized) is pervasive and unrelenting in the lives of Zen initiates at Eiheiji. Even when the hazing does let up somewhat, it remains an urgent concern: Nonomura and his fellow trainees, having completed the first part of their initiation, are expected to brutalize the newer recruits. It speaks well of Nonomura that when a nervous newbie inadvertently catches his eye in a corridor, he can’t bring himself to administer the requisite blow. Nevertheless, Nonamura seems unwilling to recognize that something has gone fundamentally awry in the traditional training of would-be monks at Eiheiji.

Or is he? That is the question I struggled with throughout “Eat Sleep Sit”: Does or doesn’t Nonomura recognize the pathology inherent in the centuries-old system of hierarchical one-upmanship and ritualized abuse that characterizes traditional Zen monastic training in Japan, no matter what occasional spiritual insight might be gleaned along the way? That he gleans such insights in the course of his training is a matter of self-report, and all in all they seem worth it to him. But the story Nonomura wrote in red ballpoint pen while commuting every day to his design job in Tokyo is at odds with the story he tells with his feet—shortly after his friend Choshu’s decision to leave the monastery, Nonomura decides to leave as well. The message of the pen seems to be that a do-or-die approach to Zen training is worth every drop of blood and tears you put into it. The feet, however, say that Eiheiji may be a nice place to visit, but you wouldn’t want to live there for a second longer than absolutely necessary. Which story is the real story? It isn’t clear. And therein lies the magic of the book.

At the heart of “Eat Sleep Sit” lies a profound ambiguity, experienced by postmodern people the world over, about age-old religious traditions that seem to embody profound spiritual truths even while they lack any real congruence with the world outside their walls. It was that ambiguity that drove millions of Japanese to embrace “Eat Sleep Sit” when it was first published in Japan in 1996—readers who, like the pre-Eiheiji Nonomura, probably had no idea what really happens behind the remote and venerable façade of Japan’s most famous Soto Zen temple. That ambiguity is also likely to engage readers of the English edition (gracefully translated by Juliet Winters Carpenter), because the fundamental question raised by the book—is religion worth all the trouble it puts us through?—is the koan of our age.

With its endless parsing of Zen minutiae and overlong disquisitions by Eiheiji’s founder, the thirteenth-century Zen master Dogen Kigen, “Eat Sleep Sit” doesn’t offer an answer to that koan. And the afterwords to both the Japanese and English editions also fail to reveal one. Fortunately, that is not the same as saying there is no final payoff for Nonomura’s efforts.

Eat Sleep Sit: My Year At Japan’s Most Rigorous Zen Temple

Kaoru Nonomura

Translated by Juliet Winters Carpenter

Tokyo/New York:

Kodansha International, 2009

328 pp.; $24.95 cloth

An odd detail crops up at the end of “Eat Sleep Sit,” a momentary tip of the hand that shows us the cards Nonomura has been holding all along. We know from the beginning that he is going to get fed up with all of this and go back to his life in Tokyo. But what happens after Choshu decides to depart is so unexpected that it simply has to be the key to understanding the whole. Nonomura tells his friend:

“That’s great, Choshu!” It struck me as a brave decision.

“Not really,” he demurred, and then asked if I’d ever seen “My Neighbor Totoro.”

It turns out that the lecture scheduled for that evening had been cancelled, and in its place the monks were to screen Hayao Miyazaki’s 1988 classic animated film about the healing power of nature, as personified by an enormous but benevolent tree spirit named Totoro. The movie, which debuted the year before Nonomura and Choshu began their training, was enormously popular in Japan, where its furry, rotund hero became the unofficial mascot of an emerging Tokyo green movement. It is the sole reference to popular culture in a book by a Tokyo designer, and is thus Nonomura’s signature moment—the moment we meet the man he was and the man he is destined to become again, once he has emerged from the time warp of Eiheiji culture.

That single reference suddenly throws the whole book into sharp relief, reminding us that apart from loneliness, violence, and deprivation, there has been another theme at work—one that passes largely unnoticed in the reading, simply because it is always there in the background—and that is nature. Nature as experienced aesthetically, in a sudden glimpse of red leaves from under the covered walkways that run up and down the vast mountain temple complex, and nature encountered in its more mundane manifestation, in long hours spent outdoors sweeping, raking, weeding, and shoveling snow. Nature is the consolation and, more often than not, the inspiration that sustains Nonomura through his year of training, and nature is likewise the point in the end.

Finally, on the eve of his departure, Nonomura comes to understand the meaning of existence solely in terms of “natural man”:

The business of living is not in the least special. In a sense it all comes down to two things: eating and excreting. These activities are common to all life forms. Every creature on earth is born, through eating and excreting helps to maintain the balance of the great chain of being, and dies. In the realm of nature, these activities are essential to the continuity of life, and they give value to each being’s life. People are no different. If human life has meaning, it lies above all in the essential fact of our physical existence in this world. This is what I strongly believe.

That “balance,” that “value,” and that “chain of being” are at the heart of “Eat Sleep Sit,” but despite Nonomura’s protestations to the contrary, one gets the sense that they are a minor, somewhat troublesome theme of life at Eiheiji, where protocol is all. Which begs an obvious question: Is the Eiheiji that Nonomura encounters in his yearlong training what Dogen really intended? That question is never really answered—which is to say, it remains a kind of koan we have to answer on our own.

Readers not riveted by the minutiae of Zen life may find “Eat Sleep Sit” slow going at times, but the overall effect of the book is striking, making it well worth the read for its portrait of the struggle to find spiritual meaning in a traditional religious setting, and the perils that often accompany it.

Clark Strand is a contributing editor at Tricycle. A former Zen Buddhist monk, he is the author of “How To Believe in God: Whether You Believe in Religion or Not” and the founder of the interreligious blog Whole Earth God (wholeearthgod.com).

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.