in the sitting hall

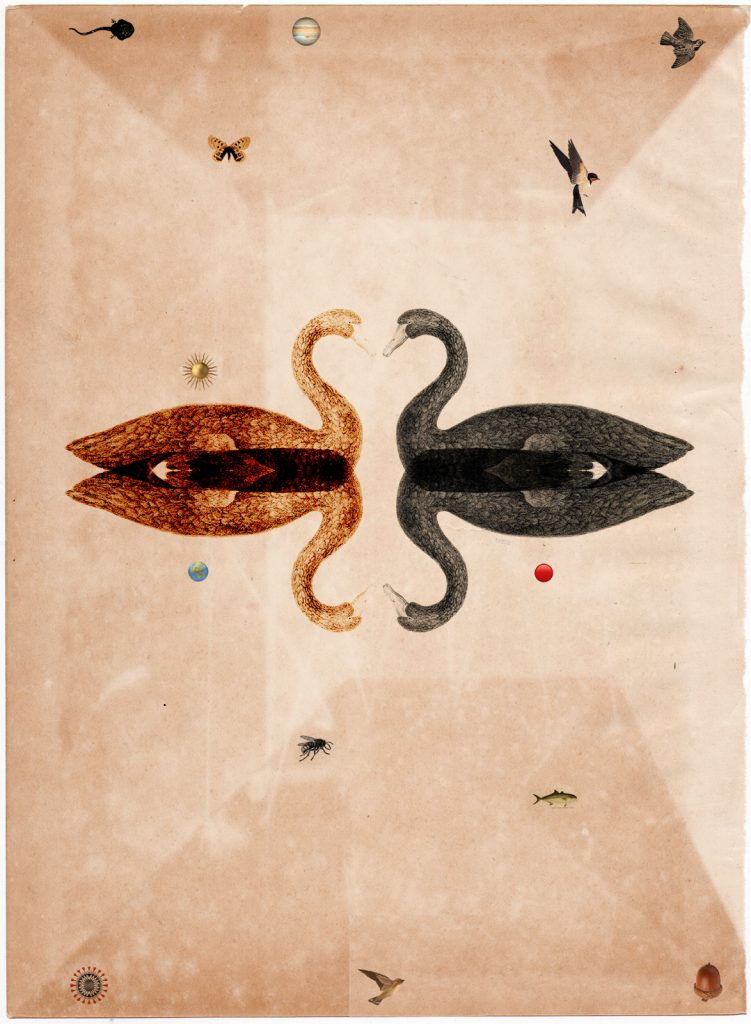

black swans gliding to stillness

saving all beings

—Lynda Zwinger

The term black swan event originated from the Western belief that all swans were white—an assumption proven false in 1697 when Dutch explorers discovered black swans in Australia. In modern parlance, the term has come to refer to statistically improbable events that “come out of left field”—especially those with a disproportionately powerful effect on history, science, finance, or technology. The winning haiku for the Winter 2021 Haiku Challenge (based on the season word swan) adds Buddhism to the mix with its allusion to the bodhisattva vow.

The “black swans” of the poem are not actual swans but black-robed bodhisattvas—Zen monks at the end of their walking meditation, “gliding to stillness” before their cushions in preparation for another period of seated meditation. In Japanese haiku, season words are rarely used nonliterally. A swan is a swan. In Western poetry, which is deeply rooted in figurative language, such constraints would be too limiting. And so the poet offers us the vision of monks in a meditation hall as swans on a quiet lake.

The style of the haiku is elegant, its image graceful and even dignified. Had the poet meant to undercut the idea that we can save others by sitting on our butts, she easily could have made the scene comedic. But no: the comparison between saving all beings and a black swan event is meant to suggest not the improbability of that event but its nonlinearity—the fact that it disrupts our narrative about ourselves and the significance of our species within the cosmos.

Every organized religion created since the dawn of agriculture has placed a premium on human destiny. Thus every religion in the world today, with the exception of those rare, vanishing outliers among Indigenous peoples, was created to answer a question the very asking of which is a form of ecological delusion: What is the meaning of human life?

The bodhisattva’s vow to save all beings is an attempt to answer that question. But the answer cannot be found through anthropocentric ways of thinking. What does it mean to save all beings in a planetary ecosystem where all matter and energy—indeed, all life—is being endlessly recycled and recirculated? Aren’t we saved already by that system?

To answer that question does not require us to think outside the box of our planet, as if we could solve our problems by migrating to Mars or nirvana (whichever comes first). Rather, it invites us to think ever more deeply from inside that Earth-shaped box, embracing its contours with every cell of our being and submitting to its limits in our actions. This is where haiku come in. Haiku teach us to think inside the box.

Surely this is what the poet’s “black swans” are doing in the lake-like stillness of their meditation hall. If ever there were a koan worth solving, this is it. The vow of the bodhisattva—to be reborn within an ecosystem as that ecosystem—may be the only koan there is.

♦

The Tricycle Haiku Challenge asks readers to submit original works inspired by a season word. Our moderator, Clark Strand, selects the top poems to be published in Tricycle with his commentary. See past winners and submit your haiku here.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.