Kosho Uchiyama Roshi (1912–1998) didn’t have much patience for ceremony, superstition, or even talk of enlightenment—all that was nonsense. His emphasis was on pure zazen. Yet in his last years, when his health no longer permitted him to sit, chanting the name of Kanzeon Bosatsu (Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva) became his primary practice. In his last book, The Sound That Perceives the World: Calling Out to the Bodhisattva, Uchiyama provides a teaching that may catch Western readers off guard.

The book is a collection of essays written not long before his death, initially titled Appreciating the Avalokiteshvara Sutra. In it, Uchiyama tells us how he came to the practice of calling out to Kanzeon, and why this practice is not different from zazen. At first surprising, the idea becomes increasingly cogent. The text was put together for publication by Uchiyama’s disciple, Shohaku Okumura, the founding abbot of the Sanshin Zen Community in Bloomington, Indiana, whose many translations and commentaries of Dogen have been invaluable for English-speaking readers for many decades. Okumura worked with Howard Lazzarini to translate from the original Japanese text.

The Sound that Perceives the World: Calling Out to the Bodhisattva

By Kosho Uchiyama, foreword by Shohaku Okumura

Wisdom Publications, 2025, 272pp., $29.95, paper

Uchiyama first encountered the practice of calling out to Kanzeon during the Pacific War (World War II in the West), when things were very rough in Japan: no money, no food, people struggling to survive. Uchiyama was living in a little temple with two other monks, the three of them determined to keep up their zazen practice despite everything. But when the government seized the temple to house orphans, they had to leave. They took a job in the deep mountains cutting wood to bake into charcoal to feed the little hibachis that heated traditional Japanese homes. These city boys who had never experienced mountain life were happy to find work and a place to stay, and they were up for the adventure. But it turned out to be an ordeal: not much food or heat, freezing temperatures and snow, and lugging heavy equipment up steep mountain paths. Without proper gloves, their hands froze almost numb from the cold and burned and blistered from pulling charcoal from the ovens.

Amid his struggles, Uchiyama came to the end of the line. He would rather die than endure one more day. And suddenly he found himself fervently chanting Namu Kanzeon Bosatsu, Namu Kanzeon Bosatsu, Namu Kanzeon Bosatsu. The bodhisattva filled his body and mind. All thoughts of misery and suffering disappeared, and he felt happy and lighthearted. He was able to continue his work and survive.

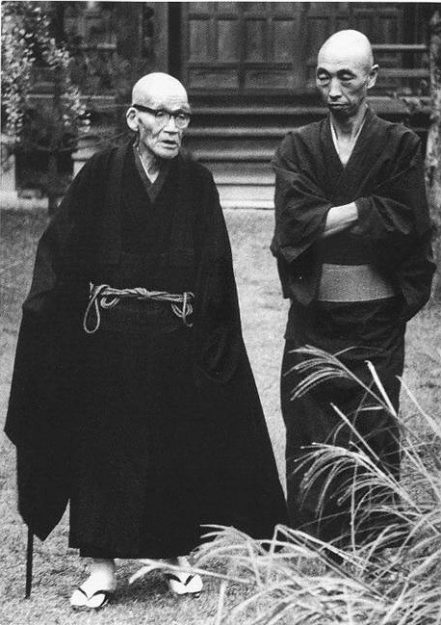

The odd thing about this is that Uchiyama was a very unsentimental person, even to the point of gruffness. Not that he was unsympathetic, but he felt that most people’s problems were due to their stupid thinking, which he didn’t want to indulge. He came from a rather unconventional lineage of priests that rejected the religiosity of ordinary Soto Zen. His teacher, Kodo Sawaki Roshi, was known as Homeless Kodo because he refused to take on a temple with its donors, social groups, memorial ceremonies, and funerals. Uchiyama thought that most of Zen, like all religions, was nonsense. Offering incense and bowing to statues was foolishness, a waste of time. He was a no-nonsense Zen tough guy, which makes his sudden, spontaneous devotion to chanting for Kanzeon’s help so surprising.

The world is not other than ourselves; we are not other than the world.

The tradition of calling on Avalokiteshvara in times of trouble comes from the famous Chapter 25 of the Lotus Sutra (the book includes a translation of this chapter and the ten-line Kanzeon Sutra, chanted in most zendos, with Uchiyama’s commentary). In this chapter, the Buddha goes on at some length, enumerating many situations where people call out to Avalokiteshvara and are miraculously delivered from their distress.

It wasn’t because he believed any of this that Uchiyama spontaneously began chanting the name of Kanzeon. It was because of his childhood conditioning. His grandfather didn’t like the local Pure Land temple down the block. Pure Land practitioners chant the name of Amida Buddha, praying to be reborn in Amida’s pure land, because practicing in this mundane world is too hard. Uchiyama’s grandfather didn’t like this idea, so he built a small temple to Kanzeon. That temple burned down, but Uchiyama’s mother inherited some of the images and prayed and chanted to them every day. So Uchiyama had this impressed upon his mind, which is why it suddenly came back to him in his hour of need.

Uchiyama recounts many stories from his colorful and surprising life. He married when he was a young university student of Western philosophy, but his wife contracted tuberculosis and died in her early 20s. Her death precipitated a spiritual crisis. He took a job as a mathematics teacher in a Catholic school, where he seriously considered becoming a Catholic priest. Though he decided not to, he continued to be inspired by the Bible, which he read regularly for the rest of his life and quoted often in his many books. He married a second time, but his wife died soon after in childbirth, along with their only child. Even though he didn’t contract tuberculosis when his first wife died, his health was somehow affected, and he was never robust afterward. In 1975, at 63, his health broke down, and he had to retire as abbot of Antai-ji, a Buddhist temple and monastery in Hyogo, Japan. After his retirement, he married a third time and lived a few decades more, writing and meeting with the many people who sought him out.

Uchiyama’s best-known teaching, “opening the hand of thought,” described in a book by that title, expresses his vision of how to practice zazen and how to live. It’s his understanding of Dogen’s radical teaching that enlightenment isn’t a state or an achievement but is life itself, seen and experienced as it really is, beyond our conceptions of it. Practicing zazen is not to change or eliminate thought so that we have a peaceful, empty mind. To practice zazen is to open the hand of thought, to allow our thought—our life—to come and go freely. As human beings, we naturally have thoughts, emotions, and self-centered desires. According to Uchiyama, these are like secretions of the glands; they come and go, and they are beautiful, not at all a problem—unless we close our hands on them. Then they cause the suffering that eventually leads to the catastrophe of the human world. But when we open the hand of thought, allowing everything to come and go, we don’t set ourselves apart; we join the flow of reality completely.

Uchiyama says that calling out to Kanzeon is the same as opening the hand of thought. Just as in zazen we allow thought to arise and disappear, returning repeatedly to body and breath, so when we chant the name of Kanzeon, we are opening the hand of thought, letting go of our self-centered habit and allowing what is to be what it is. When we do this, we are immediately freed from suffering. In the snowy mountains of Japan long ago, Uchiyama was freed from his troubled thoughts by filling his mind with the thought of Kanzeon. The weather didn’t change, his hands were still frozen and blistered, and there was still pain. But since his mind was no longer obsessed and troubled with it, there was also, at the same time, no pain. He was free of himself.

It strikes me that this teaching, surprising in itself but even more surprising given its source, is a timely one for us in the Western Buddhist movement, as the first generation of devoted Zen students (my generation) is aging and dying, and perhaps unable to do zazen at all or to do it in sesshin with the kind of intensity we once had. If chanting Namu Kanzeon Bosatsu is the same practice as zazen, then maybe there is still hope for us!

In The Sound That Perceives the World, Uchiyama makes it clear that it isn’t the magic of the words that helps you; it’s the mind that opens to the words. You could chant Namu Amida Butsu, Namu Kie Butsu (I take refuge in Buddha), or cry out to the Virgin Mary—it’s all the same.

It’s said that the difference between Zen practice and Pure Land practice is that Zen is a joriki (self-power) practice and Pure Land is a tariki (other-power) practice. That is, Zen practitioners awaken through their own effort, but Pure Land practitioners rely on the power of Amida Buddha for help. Uchiyama teaches that if you truly understand self and other, you see that no such distinction exists. What is other? It is the self. What is self? It is the other. Separation is an illusion. Life is a flow, not a collection of things. The world is not other than ourselves; we are not other than the world. To see and to live this is awakening. Now, when sitting is no longer easy or even possible for so many of us aging Zen practitioners, calling out could be a way forward, as it was for Uchiyama.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.