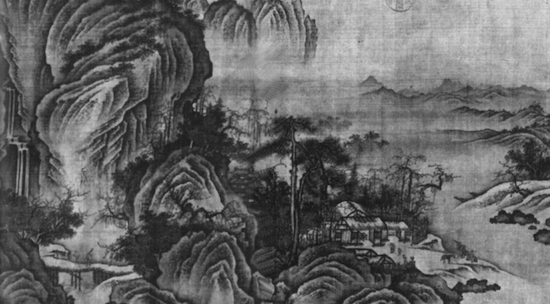

Gnarled pines, wind-blown clouds, jutting mountain pinnacles, exiled scholars, horses, trailing willows. Moonlight on meandering rivers, fishermen, white cranes and mandarin ducks, the eerie screech of a gibbon, tiny white plum blossoms on twisted branches, a battered wooden boat moored in the distance. For more than a thousand years the poets of Buddhist China wandered a landscape that is vast and at the same time intimate, mysterious and deeply familiar: the same mountain peaks, the same villages, the same river gorges. What makes this landscape feel so much like home? The poets of China, many of them Ch’an practitioners, had a way of quickly getting down to elemental things. Using a vocabulary of tangible, ordinary objects, they composed unsentimental poems that seem the precise size of a modest human life—the reflective sadness, the fleeting calm pleasures.

As Buddhists, these men traveled a great deal. When reading their poems you observe how deliberately they led, as Thoreau would have put it, hyper-aethereal lives—“under the open sky.” It is no accident, then, that a prevalent theme in the poetry is the farewell poem for a comrade, typically situated at daybreak after a night of wine or tea, vivid talk or silent companionship. These poets spent their days living in and journeying between the numerous Buddhist sites of pre-modern China—village temples, remote points of pilgrimage, monasteries tucked deep within forests, the mountain yogin’s hut in a secluded mossy gulch. Over the several millennia of recorded Chinese history, political and military events have been shifty and uncertain as well. Scholars, poets, civil servants, Buddhist abbots, and even monks of no reputation were driven from region to region, into exile through windblown mountain passes, or when the regime shifted, recalled up a thundering river gorge to serve in some official capacity, often memorializing the journeys in poems.

In the poetry a clipped, selective vocabulary, surprisingly ambiguous in the Chinese originals, merely suggests “what’s out there.” It is up to the reader to fill in the details—tumbling watercourses, looming peaks, twisted mountain strata, lowland pools, deer and wild gibbons, wind-stunted trees. Always alongside the poet, non-human creatures move easily in the world of his poem. Deer and wild cranes may follow their own tracks, but their travels seem to meaningfully crisscross the poet’s. At times untamed creatures become, with only a touch of irony, profound teachers for the wandering-cloud poets. By an interesting karmic twist, these various citizens of Chinese verse have in recent decades sensitized American readers to distinct features of our own continent: watersheds, seasonal cycles, animal habits, plant successions, and the like have taken up residence in our own thoughts, artwork, and poems.

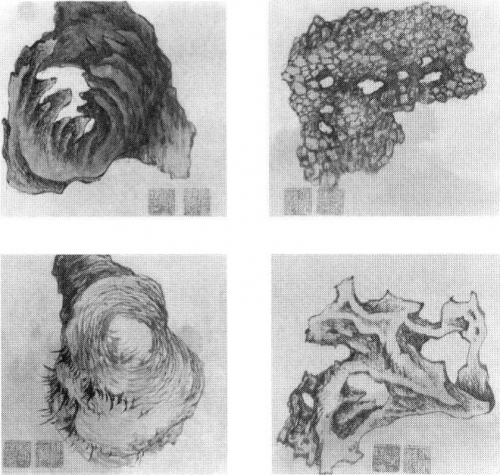

In China, there was even a “nature poetry” of almost comic literalness: shih-shu, “rock-and-bark poetry.” It is uncertain how widely the phrase circulated, but shih-shu were colloquially written, mildly irreverent poems, poems not simply skeptical of city-folk hustle nor merely celebratory of reclusive hours spent in savage wilderness settings. They went farther. Shih-shu were written on scraps of bamboo rather than being brushed on silk or paper. They were scratched into bark, on rocks, or pecked into cliff faces. The most notorious practitioner of this genre, and maybe the originator of shih-shu, is the poet Han-shan (possibly seventh century), known to American readers as “Cold Mountain.” Translations by R.H. Blyth, Gary Snyder, Red Pine, and Burton Watson have made him well known in recent decades.

According to Lu-ch’iu Yin, a minor T’ang government official and Buddhist enthusiast, Han-shan’s gatha, or Buddhist verse, were left littered about the forbidding cliff from which he took his name. The Han-shan promontory lies along the T’ien-t’ai range in Chekiang, a strikingly wild country in southern China. Contemporary photographs show cornfields beneath the soaring rock wall, but in Han-shan’s day the land was heavily forested, and local woodcutters or monks out gathering brush occasionally saw the poet disappear into a cave, which in some unsettling accounts would close up behind him.

Unable to coax Han-shan, a man he deeply admired, into establishing closer ties to the world of civilized people (Han-shan just giggled, threw things, and ran into the woods) the well-intended Lu-ch’iu Yin sent a troop of men into the mountains to collect what of the scattered poems they could find—about three hundred in total. The legend of ragged Han-shan and his equally eccentric comrade Shih Te became a reference for countless later poets, who saw in their cryptic behavior—as much as in their poetry—a deep Buddhist realization. In the 1960s, California poet Lew Welch, much taken with Chinese scholar poems and the habits of Ch’an hermits, is said to have left the sole copy of one of his own poems tacked to a barroom wall in Sausalito.

The karma runs deep. In the late 1980s a group of American poets gathered one spring at Green Gulch Farm’s Zen Center, twenty minutes north of Sausalito, to talk about poetry and Buddhist meditation. It marked the first time such an event had been convened east of the Bering Strait. Billed as “The Poetics of Emptiness,” the gathering hosted the usual cast of characters: blue-jeans bodhisattvas, long-haired yogins, quick-witted yoginis, nautch girls, coyote men, patch-robe monastics, and unemployed scholars. The gathering caught the echo of earlier events, “Ch’an guests and poetry masters,” that by the eighth century had become regular practice in China.

That particular weekend, in a pond in back of the drafty Green Gulch zendo, a frog sangha held its own convocation—like the gibbons and wild cranes of Chinese verse—while many good human remarks were made during the indoor conferences. One statement in particular has stuck with me. The poet-priest Norman Fischer in a very unsensational fashion said, “Meditation is when you sit down and do nothing. Poetry is when you sit down and do something.” With these sage words, he neatly wiped out centuries of debate—in India, China, and Japan—over whether poetry is a legitimate pursuit for the earnest Buddhist in search of realization.

Yes, meditation and poetry. It is hard to imagine with what sobriety the early Buddhists in India enjoined monks and nuns against literary pursuits. It is equally striking that as late as 817 C.E. the renowned Po Chu-i could write:

Since earnestly studying the Buddhist doctrine of emptiness,

I’ve learned to still all the common states of mind.

Only the devil of poetry I have yet to conquer—

let me come on a bit of scenery and I start my idle droning.

—Translated by Burton Watson

Without doubt, these two distinctly human undertakings, making songs and watching Mind, go inestimably far back into prehistory. Would contemporary North American consumer culture offer a bemused smile to the notion of a conflict between them? Aspirants watch out! There seems so little time these days, and hopelessly little reward, for practicing either. Yet a not-so-secret, and surprisingly durable, counterculture keeps the two alive, evidently unable to do without either. Often the two get pursued hand in hand, or, as Norman Fischer noted, in nearly the same posture. Luckily, as North Americans, we don’t have to cut back too much growth in order to keep the hall of practice clear. Behind us stand heartening documents from Asia, compiled over the course of several thousand years, to show what others have done.

Americans of many backgrounds, who not many decades ago admired and cultivated a lean, resolute character, were hungry for access to these traditions—the bitter tea of Ch’an Buddhism, a poetry with the taste of gnarled wood. After all, how many among us first learned poetry skills by rewriting some old Chinese poem? How many among us got our first taste of Zen by copying a detail out of the life of some Chinese hermit met in a book? Or saw an ink-brush scroll in which a thin stream drops from cloud-piercing pinnacles—then noticed a tiny pavilion, one quiet scholar gazing into the void—all done in a few confident strokes?

Much of the poetry came into American translation after the Second World War. Scholars and soldiers who saw action in the Pacific theater brought home with them a bit of Asian culture. Kyoto in the mid-fifties developed a lively expatriate group of poets, translators, Zen students, and scholars. Young writers in the States, spurred to the modern flavor of shih (poetry), were able to book cheap passage to Asia by boat, or to travel there figuratively by staying home, drinking tea, and getting Chinese ideograms under their belts. One of the influential publications of the time was Gary Snyder’s translation of twenty-four Han-shan poems (1958), which thousands of Americans read. That same year Jack Kerouac’s book The Dharma Bums gave Han-shan and Zen Buddhism the flavor of cultural revolution. “I see a vision of a great rucksack revolution, thousands or even millions of young Americans wandering around with their rucksacks, going up the mountains to pray, making children laugh and old men glad. . . Zen lunatics who go about writing poems.” Ch’an Buddhist poets seemed right up to date.

What was so modern about these old poets? Kenneth Rexroth wrote of Tu Fu (712-770): “Tu Fu comes from a saner, older, more secular culture than Homer, and it is not a new discovery with him that the gods, the abstractions and forces of nature, are frivolous, lewd, vicious, quarrelsome, and cruel, and only men’s steadfastness, love, magnanimity, calmness, and compassion redeem the nightbound world.” He also said, “Tu Fu is not religious at all. But for me his response to the human situation is the only kind of religion likely to outlast this century. ‘Reverence for life,’ it has been called.”

Reverence for life (Sanskrit ahimsa: non-injury, no wanton killing) was a cornerstone of Buddhist practice in India long before a few first sutra literatures took the rugged northeast road into China, influencing every major poet until modern times. Maybe we’re in a position now to see that this is what’s so compelling in 1500 years of Ch’an poetry: a simple reverence for life. The best poems merely display it and move on: pushing no doctrine or dogma, no jingo, no proselytizing. The Buddhism is carefully hidden away in tight five- and seven-syllable lines.

In 1915, Ezra Pound had compiled a book of Chinese verse, mainly drawn out of Li Po (701-762), while young men across Europe were fighting in trenches. It seems he conceived Cathay as an anti-war book, not as propaganda, but as the effort a poet might make in order to shift the way people see things. Today, at the turn of a millennium, such old poems still taste modern. Why is it that behind the stolid, often melancholy tone of so much Chinese verse, modern ears detect an acute comradeship with all forms of life? Nearly as far back as Chinese literature goes, one encounters the term the ten thousand things, Taoist shorthand for the planet’s numberless creatures, a phrase that manages to be tender without sounding maudlin. “Sentient beings are numberless, I vow to save them,” goes the chant in the zendo. This camaraderie, or instant sense of warm-heartedness, is what makes such a contribution to Buddhist literature, to ecology ethics, and to postmodern poetry.

Chia Tao (779-843)

The solitary bird

loves the wood;

your heart also

not of this world.

—Translated by Mike O’ Connor

Ch’i-chi (864-937)

On my pillow little by little waking,

suddenly I hear a single cicada cry—

at that moment I know I have not died.

—Translated by Burton Watson

Pao T’an (Tenth Century)

Frosty wind

Raises deep night,

Missing only

A gibbon’s howl.

—Translated by Paul Hansen

Dogen Zenji, the thirteenth-century Japanese philosopher versed in Ch’an practice, picked up the spirit in his own cranky, mischievous way:

That the self advances and confirms the ten thousand things

is called delusion;

That the ten thousand things advance and confirm the self

is called enlightenment.

—Translated by Hakuyu Taizan Maezumi

There is good testimony that long familiarity with meditation—months, years, decades—contributes to a person’s clear-headedness, focus, and good humor. Beyond such personal benefits, it’s also possible you become a better citizen. A heightened sense of empathy seems to emerge—one that even crosses the boundaries between nature’s “kingdoms,” human, animal, insect, or plant. Tibetan Buddhists vow to liberate all beings, down to “the last blade of grass,” and ecologists of many persuasions are currently naming and vowing to save, yes, a last blade of grass.

Perhaps there was a time when poetry didn’t pay much attention to these things. But if the ecologists are right, we currently dwell in a period the future will know as “the great dying.” Edward O. Wilson and a range of other accomplished scientists give hard and compelling evidence that we little humans are bringing about the fastest wave of species extinction known in the four-billion-year history of our blue-green planet. Maybe one of the consciousness-shifting tools we humans can use if we hope to turn this around is the poetry left by departed Chinese masters. I expect it will be their poems of invisible Buddhist insight, wrapped in mist or moonlight, pulsing with a quiet compassion, and not the poems of an expressly doctrinal character, that will give us our best bearing.

Chih Yuan (b. 976)

Chih Yuan (b. 976)

Living in Poverty

The stove

In my mountain kitchen

Is tracked with blue moss.

Dust fills the almsbowl.

There isn’t any food.

A pity

Mice and sparrows

Haven’t learned about poverty yet,

Drilling into the room, drilling

Through the walls.

—Translated by Paul Hansen

Chia Tao

Seeking but Not Finding the Recluse

Under pines

I ask the boy;

he says: “My Master’s gone

to gather herbs.

I only know

he’s on this mountain,

but the clouds are too deep

to know where.”

—Translated by Mike O’ Connor

Ch’i-chi

Little Pines

Poking up from the ground barely above my knees

already there’s holiness in their coiled roots.

Though harsh frost has whitened the hundred grasses,

deep in the courtyard, one grove of green!

In the late night long-legged spiders stir;

crickets are calling from the empty stairs.

A thousand years from now who will stroll among these trees,

fashioning poems on their ancient dragon shapes?

—Translated by Burton Watson

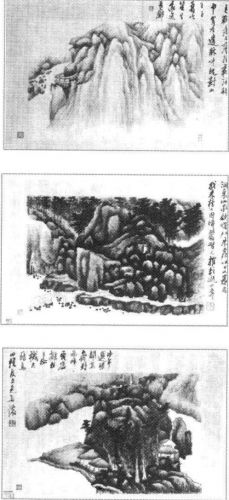

Han-Shan Te-Ch’ing (1546-1623)

(from Twenty-Eight Mountain Poems)

21. Who can be a wild deer among deserted mountains

satisfied with tall grass and pines

if the realm of dust was an endless dream

how then did heroes reach the land of peaks

22. My long white hair is framed by green mountains

my body is surrounded by a thousand cliffs and gorges

the pine gate is silent no one passes by

the only ones who visit are drifting clouds

—Translated by Red Pine

Andrew Schelling is an award-winning poet, essayist and translator on the faculty of The Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado. This essay is adapted from his introduction to The Clouds Should Know Me by Now: Buddhist Poet Monks of China, edited by Red Pine and Mike O’Connor, from Wisdom Publications.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.