An interview with Joanna Macy and an excerpt from her new book Joanna Macy’s memoir Widening Circles covers her early years as a student of theology, a stint with the CIA, and travel with the Peace Corps to Africa and India with her husband and three children. Here she speaks with Tricycle about a crucial stage in the formation of her personal and political understanding.

You devote a chapter to the time you spent studying the Sarvodaya movement—the Buddhist-inspired community development program—in Sri Lanka. When I first dove into the dharma in India with the Tibetans I had this hunch that the teachings of the Buddha could free people to respond creatively and fearlessly to the needs and challenges of their society. Then, when I later visited Sri Lanka in the course of my doctoral work, I was astonished to find that here was a whole movement, the Sarvodaya movement, active in thousands of villages, that was already doing what I had imagined might someday be possible.

What I witnessed with the founder, Dr. Ariyaratne and the villagers, and the monks who were involved in the movement, has in fact inspired me in all the social action work I’ve done in the twenty-four years since I first met them.

As you know, Sri Lanka is suffering a bloody and tragic civil war, now in its seventeenth year. As I look back on my time with Sarvodaya, in the late 1970s and early 80s, I see a precious historical moment, an island in time, that showed us how the Buddha-dharma can be a force for social revitalization. What I saw then still inspires me now. Indeed, Sarvodaya’s work in those earlier years built structures and relationships that have mitigated the effects of the ethnic warfare, enabling people on both sides to connect with and help each other where they can.

You talked in the book about a moment when you realized that the self can be “released into action” through the practice of dharma—can you say something more about how Buddhism specifically can spur social action?

When we brought Buddhism to the West we lost sight for a while of the strong social and political message of the Buddha-dharma. That was because, coming out of nineteenth- century liberal religion with its busy, outer-directed social gospel, we were looking for a contrast, a more introspective contemplative spirituality. The interiority of the Eastern religions appealed to Westerners very much, including Western scholars, who created anthologies of Buddhist texts which featured that inward-looking dimension.

But in my graduate studies I was excited to discover a good number of early discourses of the Buddha specifically directed to issues of social and economic justice, equality, and responsible self-governance. As a matter of fact, Ariyaratne claimed in one of our conversations that “eighty-seven percent of the Buddha’s discourses” dealt with how we live together in society. Well, I wasn’t sure about that, but I did feel that the Buddha’s social message had been largely overlooked in the West, and I had a tremendous appetite to find these discourses, and the insights they held.

So you can imagine my gladness when I first walked into Ari’s office in 1976. Right away I thought to myself: This is where I want to come and be—I wonder if I ever could? But he invited me. And I did. And I am eternally grateful. My sense of what is possible was expanded by Sarvodaya, and it’s never gone back.

Excerpt

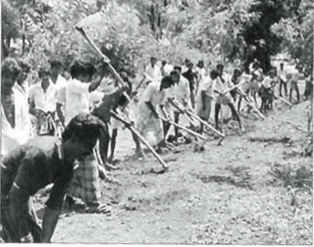

Much of my “participant observer” research entailed interviewing Sarvodaya monks, for the more progressive ones offered vivid examples of the role that clergy can play in social change. They opened their temple precincts to Sarvodaya “family gatherings” and preschools and classes. They drew from old Dharma stories to teach courage and self-respect. They used their status to draw villagers together in “family gatherings,” recruited school dropouts to help organize shramadanas [voluntary work camps], and encouraged the young women and girls to take part. By their very presence they stilled any disapproving gossip about village daughters mixing with boys. My hunger for these lessons was insatiable.

A good number of these monks were accessible within an hour’s ride of my village home. I would head off on my motorcycle of an afternoon, notebook in saddlebag and Ramani perched behind me. A bright eighteen-year-old, Ramani served as my local interpreter, for my Sinhalese was inadequate to discussions of philosophy and social change. Ramani was Christian, which accounted for her spunky readiness to straddle the rear seat of my motorcycle as we careened down the packed dirt roads; Buddhist females were conditioned to be more shy about their person, and less venturesome. Across the countryside we sped, singing rounds—our favorite of the season was “Happiness runs in a circular motion”—til the gleaming dome of the dagoba that was our destination appeared round a bend. We would park Pruey [the motorcycle, named after a favorite family game] by the gateway of the temple’s compound and cross the broom-swept sand to look for our monk in the open-walled preaching hall, or inquire for him at the door of the vihara. Ah, there stood our venerable bhikkhu, all smiles. In a swift gesture of reverence that now felt natural to me, even good, I ducked to touch the monk’s feet, or the ground before it.

Our hands must not meet, I had learned, for unlike my Tibetan monk friends, bhikkhus of the Theravada school of Buddhism are not to be touched by a woman. Then I scuffed off my thongs to follow him in to tea and conversation. The seats Ramani and I took were a hair lower than his own chair, but the tea was the same: strong, milky, sweet. I tried reckoning once the quarts of tea an Asian Buddhist monk must drink every day; no wonder so many become diabetic. Over tea, the talk was of my host’s work with the villagers, his life in the Dharma. Sometimes the temple was still, suspending us in the fly-buzzing timelessness of mid-afternoon. Sometimes we talked amidst a continual traffic of novice monks, devotees, local teachers and organizers, temple workmen, children, dogs. Whenever I called on my bhikku friend Samitha, a Marxist with the build of a rugby player, his pet mongoose would slink between our legs.

What I loved most, as we spoke of village plans and scripture passages, was the scent of courage. I never heard a word of complaint from Sarvodaya monks, but I began to realize the price they paid for engaging in community development work. It was more than the time it took, added on to hours of puja, temple care, and pastoral duties. It was more than the physical exertions involved—leaving the tranquil comforts of the temple for the wattle-and- daub shacks of the poorest families, or the brain-addling sun of a shramadana, or the daunting bureaucratic labyrinths of government. The harshest cost was in reputation and prestige. One was not applauded by the larger, traditional sangha, nor by the larger, conservative laity. On the contrary. The forest-dwelling monks in meditative retreat, and the scholarly ones in their libraries, received the most reverence. Their kind of renunciation did not rock the boat. When I had the nerve to ask Sarvodaya monks outright, the calm answer was yes. “Yes, that is true, by engaging in social change work we lose some measure of respect, we are considered a lesser kind of monk. It doesn’t matter. It makes no difference.

Widening Circles, by Joanna Macy, was published by New Society Publishers in September 2000.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.