The thing about zen practitioners is that we are neat. Annoyingly, militarily inspected, white-glove neat. There’s indeed a place for everything, and everything has its place.

That’s why I’m so perturbed right now. I have lost my first robe.

For nearly thirty-five years, I’ve kept my robes in my home shrine, a petite metal cabinet with a wood top—once used by printers when presses were analog—with three small sliding drawers with circular metal pulls. The larger drawers underneath are for my kesas, the full robes that are the accoutrement of Zen priests. On top is my Buddha statue, eyes open, cast slightly downward, keeping an eye on the robes, and everything else, while I go about my day. Between them is my rakusu, an abbreviated robe that hangs around the neck, a fourteen-by-eight-inch postage stamp that expedites one’s delivery to Buddha.

But the rakusu is not in there, and it should be.

I looked in all the usual places, and to be truthful, I spent a minute or two thinking my wife might have moved it absentmindedly. Of course she hadn’t, but that didn’t stop me from wondering if she had, because this is so unlike me. I mean, I’ve searched throughout the house for hours, and it’s nowhere to be found. I’ve not looked in the trash, because it would be too much to ponder how it could end up there. It’s a lost robe.

The rakusu was given to me by my Zen teacher Bernie Glassman, from whom I received the sixteen bodhisattva precepts. On the back, Bernie inscribed this dharma poem:

Lost in the haze of the dark moon’s light

Mumbling poems

Abide nowhere

The precept ceremony, or jukai, took place in 1986 at the Omega Institute, in bucolic Rhinebeck, New York, following a workshop that I had organized to be co-led by my father, Ray OK of AA fame, and Bernie. It was called “The Monk and the Drunk.” The workshop was years in the making. First, there was the matter of trust. Bernie had long since earned my trust, but he had to earn my father’s as well, and he and Bernie were an unlikely pair. A former professor of law at a Catholic university and a stern taskmaster, my father had strict standards, and his demeanor could be foreboding. One false move, and you’d suffer his easily administered wrath, memories of which still haunt me.

During a visit Bernie and I made to the Franciscan Friars of the Atonement in upstate New York in 1986, Bernie had witnessed monks running a rehab for alcoholics, and he’d become fascinated with the 12-Step Recovery model. He even adapted it for his own Zen study program, which he called the Yellow Brick Road.

Now here we were, my father, Bernie, and I and the Buddhist precepts. My father not only sat through the ceremony, he supported it. This was a testament to his openness and to Bernie’s capacity to meet people where they were and find common ground.

Had my father known that I was looking for things in Bernie that I had longed for and found sorely lacking in him and in our relationship, I doubt he would have been so keen to connect with Bernie. But because I am Irish-American, and to that end, I found discussing relationship issues with my father a nonstarter, Dad never knew from me just how traumatized I had been by his combination of alcoholism and narcissism.

But maybe he did get the message. Because in 1978, I was fortunate enough to land the role of Ben in the film The Great Santini, in which I played novelist Pat Conroy’s alter ego, the sensitive son of an alcoholic and domineering fighter pilot. The way I was able to go toe-to-toe with Robert Duvall as the father, in the emotional interplay that is the film’s central story, might have made it clear to my father, and to anyone who knew us, that to me he was a brutal tyrant.

Ray O’Keefe was nothing like the public persona he’d cultivated as an AA circuit speaker. In those venues he was hilarious, insightful, and full to the brim with rhetorical awareness that allowed him to convey the central tenets of AA to thousands. At home, he was a domineering, self-absorbed chauvinist who destroyed the childhood of his seven children and crushed the spirit of his wife. He was so effective at the latter that she often appeared dazed, with a bizarre detachment that she seemed never to have become aware of. My father used his talents to his advantage in treating his wife and children as if they were hostile witnesses in a show trial he was conducting. This was all the more pitiful because my mother adored him. As young kids, so did his children. But he was only too eager to convey at any and every juncture his resentment of us for holding him back from fulfilling his potential and ruining his life.

At the time of the ceremony, however, that was, in a way, ancient history. My father and I had come to share common ground in recovery, and that framed our guarded but respectful adult relationship. And as for Bernie, surely he could never let me down in that way. His mission, after all, was to teach a path of embodying Buddhist compassion through social action. I was certain nothing would derail my relationship with him and that he was beyond reproach.

Over time, a most curious thing happened. I woke up to the fact that my priesthood was a habit, not a practice.

In 1994, I ordained as a priest in the Zen Peacemaker Order, the newly minted social action order Bernie had started with his wife, Jishu Holmes. It was for me a powerful ceremony. Both my parents attended, as did my then-wife, the singer Bonnie Raitt, her mother and stepfather, and some of my closest friends. After my head was shaved and the long robe affixed to my frame, Bernie and three of his successors circled me three times, bowing and chanting “Buddha becomes Buddha, and Buddha bows to Buddha,” while I stood above them on a raised platform, my hands together in gassho.

After the ceremony, we all gathered on the porch of the Greyston Foundation, with its magnificent view of the Hudson River. Formerly a cloistered nunnery, the site was now home to Maitri Center, an outpatient medical facility for people living with HIV/AIDS, and Issan House, a residence for inpatient care. After creating the Greyston Family Inn, which provided permanent housing for folks coming out of temporary shelter, and the Greyston Bakery, which hired and trained the unemployed and the formerly unemployable, Bernie had acquired the former nunnery. Now, it too was part of what he had masterfully brought together in what he called his Social Action Mandala. Bernie’s approach to social action had had a huge impact in the Western Buddhist world, and I felt privileged to be playing a part in it. He was at the height of his powers, which were formidable.

B

ernie Glassman was the first successor of Taizan Maezumi, the founder of the Zen Center of Los Angeles (ZCLA) and one of the pioneers in introducing Buddhist practice to Western students. Maezumi Roshi had the rare, perhaps unique, distinction of having received full dharma transmission in three different lineages of Zen. He radiated a powerful mix of inner calm and firebrand intensity that was captivating.

Bernie was indisputably Maezumi Roshi’s senior-most successor. Born and raised in Brooklyn, Bernie completed his PhD in mathematics at UCLA, after which he went to work in the aerospace industry. He began his Zen practice from books and became a student of Maezumi in 1965. He was from the beginning both Maezumi’s most advanced student and his right hand. Bernie was built like a longshoreman, with a slight gut owing to his affection for pizza. With his shaved head and bushy eyebrows, he resembled Bodhidharma, the legendary figure who brought Zen from India to China in the 6th century. I adored him.

At the ceremony, I was given the name Daigu Angyo, or Great Fool Peacemaker. In all the photos I have from that day I exhibit a curious physical trait. I had my right forefinger on the indented space above my upper lip. Photo after photo shows me with the tip of my forefinger in the little indentation. It’s a distinctive gesture, and one I was unaware of at the time. Years later, while looking through a family photo album, I saw it again. In one childhood photo after another, I have my right forefinger pressed into the same spot, in a gesture of uncertainty and reflection.

While I had learned to be outwardly confident and expressive, I had an inner knot of withheld rage that was weapons-grade.

As I child, I was less likely to speak than to puzzle out my feelings. And considering my dark past with my father, which I was hoping to resolve as a meditation student, it’s no mystery why that gesture reemerged at my ordination. While I had learned to be outwardly confident and expressive, I had an inner knot of withheld rage that was weapons-grade. The little finger was poised, stirring the memory of previous selves and perhaps the longing to awaken the original self.

As Bernie’s Zen social action movement gained steam, it also began to garner public attention. It was documented in the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal and covered by CBS News Sunday Morning. In time, as the Zen Peacemaker Order took shape, many other venues took notice as well. And for us members of the Order, the practice and commitment deepened.

This is what Zen priests do, I thought. They contribute everything they can.

During this time, I was a cast member of the TV show Roseanne. My paycheck was the largest I’d ever received, and I tithed 5 percent of my gross income—several thousand dollars a month—to Bernie and the Order. This is what Zen priests do, I thought. They contribute everything they can. So when Bernie called and asked for an additional donation to establish a residence for members of the Zen Peacemaker Order in downtown Yonkers, I was only too happy to step up and contribute another $50,000.

This is what it will take, I thought. Yonkers was already the hub of our activities, but we had no place to congregate, socialize, and live together as we studied the Peacemaker path. As he knew, I felt we needed that, and I felt fortunate to be in a position to help make it happen.

“Bernie, your students need to know where you will be,” I had said, meaning of course that he would be in Yonkers.

“No doubt,” Bernie said. “No doubt!”

I was all in. I’d found the perfect foil to my father’s alcoholic and inconsistent presence, and I could move forward knowing that Bernie could never, and would never, act in such a capricious and hurtful way.

Two weeks later, he announced that he was abandoning Yonkers. The entire Greyston project was to be turned over to others to run. The House of One People, the Interfaith temple we had started, was abandoned. Bernie and Jishu were moving to Santa Fe, where he would drastically reduce his teaching schedule. Anyone interested in the Zen Peacemaker Order had to pivot with him. The whiplash this announcement induced proved too much for some of his students, but a core group, myself included, were willing to go along.

Though it was difficult to imagine that over a decade’s worth of practice and activism would be left behind, Bernie was always capable of radical shifts. Over the years, many students had already left him, and many more would in the future, but this never deterred him. I’d prided myself on being able to roll with the changes. And I was willing to do so again.

I called Bernie and explained that, while I thought it was his prerogative to live and teach wherever he wanted, I wanted him to return my donation for the residence building in Yonkers. I’d made clear why I made the donation, and Bernie was abandoning that project.

“It’s being used for other things,” he said evenly.

I was stunned.

He then suggested that, if I needed cash, one of his students could provide me with a loan. I didn’t need a loan. I didn’t need back the $50,000. I needed him to acknowledge that he was abandoning his vision for his community, and I needed to know that he would adhere to some basic values as he did so. But I couldn’t muster the wherewithal to say any of this. The level of shock and feelings of betrayal were too much. So I remained silent.

Bernie and Jishu moved to Santa Fe. Ten days after they arrived, Jishu died.

T

he Upaya Zen Center in Santa Fe, New Mexico, started by Joan Halifax, a noted anthropologist and a successor of Bernie’s, is an idyllic collection of adobe-style houses that is worthy of a piece in Architectural Record. After making the move there, and barely unpacked, Jishu suffered a massive heart attack. It was Bernie who told me the news that she had died when I called Jishu’s hospital room to check on her.

Flights were booked, plans were made, and students and the lineage holders came to Santa Fe to hold ceremonies and grieve with Bernie. Upon arriving, I came into a room where many had already gathered. I placed my right hand on Bernie’s left shoulder as he sat stricken with a loss even he had trouble processing.

“I knew you’d come,” Pat O’Hara, one of Bernie’s successors, said. She knew that because she knew I was devoted to Bernie and would do anything to support him.

A day later, during a break from the funeral planning, I found an appropriate time to respectfully broach the subject of the donation. He replied by pointing to a building on the property. “It’s right there,” he said.

This was woefully inadequate. My heart sank, but my consciousness remained on the surface, like a plastic bobber placed on a fishing line several feet above the bait. The catch was dwelling near the bottom, and the bait was set, but I was stuck on the surface, connected to but not part of the primary action of landing the fish. For many years after, I saw myself on the surface of this event. It wasn’t until I was married, had a child, and was drifting away from Zen practice that I began to feel I had been played. But at the time, while I lingered on the surface, Bernie caught the fish.

Just as I had never spoken with my father of the trauma he’d inflicted during the alcoholic tornado of my childhood, I couldn’t find a way to convey to Bernie and his community the depth of my feelings of betrayal. So I kept them hidden, even from myself.

After Jishu’s funeral, we said our grief-ridden farewells, and I went on to northern California to attend a retreat with Maezumi Roshi. Then in his mid-60s, Maezumi had come to preside over a large community of practitioners in multiple locations. His realization was evident, and his sense of humor was pure genius. No one could elicit a laugh like Maezumi Roshi.

Once Bonnie and I did a three-day retreat with Roshi, and Bonnie kept falling asleep in the hall.

“Maybe I’m doing it wrong,” she said. “Maybe I’m resisting it because it’s really your thing, not mine. Maybe meditation is not for me.”

“You have an interview with one of the most highly regarded Zen masters of his generation coming up,” I said. “Why don’t you ask him?” So she did.

Seated, “eyebrow to eyebrow,” in the fashion of formal Zen interviews, she related all that she said to me, and then Roshi leaned toward her, saying, “You’re falling asleep because …”

Yes, she thought. This is it. The great Zen teaching.

“You. Are. Tired,” Roshi said. At that, they both just broke up.

It was easy to develop a relationship with Maezumi. I’d spent numerous summer study periods with him at Zen Mountain Center, in the San Jacinto Mountains, high above Palm Springs. We’d become close doing the landscaping on the property, for which I was cheap strong labor working side-by-side with him. Roshi was a kind of enlightened designer, who loved setting stones, digging ground, and clearing brush, even as he casually imparted Zen teachings in this relaxed and intimate setting.

The retreat in northern California turned out to be the last time I saw Maezumi Roshi. During a trip to Japan, he died suddenly. We were told that, while visiting his family, his brother found him in bed, having passed away of natural causes during the night. Now, his students at ZCLA and his other centers had to pivot. And they did. They’d done it before. In 1982, ZCLA imploded, and his drinking was a big part of it. He’d entered alcoholic rehab, but he’d never maintained sobriety.

It was only in 1999, four years after Roshi’s passing, while I was living at ZCLA, that I learned the truth about his death. After a night of drinking with his brother, he slipped into a furo bath, passed out, and drowned. This news was conveyed to me mid-retreat, and it broke my heart. For forty-nine days after, I offered incense, flowers, and, instead of water, vodka at a private shrine I kept for him in my tiny Zen Center apartment. “Here, Roshi,” I would say, as if in a bar, drunk to drunk. “Have another.”

Upon reflection, this period of living at the Zen Center was the only time I really lived in a priestly fashion. But upon further reflection, I was still not at ease with that role, and it would take years to sort out why.

I’d viewed becoming a Zen priest as akin to marrying the universe, and in a way, this is reflected in the student/teacher relationship. The vows are taken with one’s teacher, and the practice is completed through them. The time spent with them, the many interviews, the innumerable questions and the answers were more like a marriage than any other relationship. My Zen Peacemaker marriage ended painfully. I had placed my faith in Bernie, and when that relationship crashed, something of my sense of myself as a priest went with it. I was left with a longing for rectification that never came.

Although I initially came to Zen to study meditation as a recovering addict, after Bonnie and I divorced 1999, I experimented with social drinking. It sounded good, but it didn’t work, and I resumed sober living again in 2006. Unlike Roshi, I was one of the fortunate ones. In 2010, I met my wife, Emily, and our son, Aidan, was born in 2012. Neither of them has ever seen me drinking or getting high, and I fervently believe they never will.

Parenting was an eye-opener in so many ways, one of which was that I knew I needed to be there, in the room, with my son as much as possible. I simply couldn’t justify going away to Zen temples to sit quietly all day long as he grew up. Something had to give.

Over time, a most curious thing happened. I woke up to the fact that my priesthood was a habit, not a practice. It proved no match for the teaching my family was providing me at home. This left me wondering just what my spiritual status was and how best to embody it. I came to realize that I was no longer a priest.

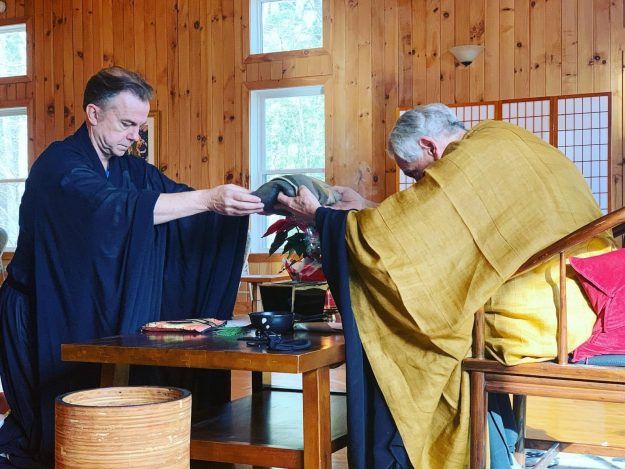

I asked my friend Fleet Maull, a successor of Bernie’s, to accept my robes in a ritual of our creation. It was essentially the same ritual as ordination, but instead of professing the home-leaving of the Zen priest, I was renouncing it. At the ceremony, bells were rung, bows were made, the vows were made asunder. And then I was no longer a priest. Which brings me back to the lost robe.

I gave my priest’s jacket and one of my kesas to a student of Fleet’s. I gave Fleet one rakusu, one of Bernie’s, and another, a gift from Maezumi Roshi, I gave to ZCLA’s then-abbot Wendy Nakao. And the robe I wore at my ordination, my personal kesa, I took outside to a fire pit at home and burned it, sending it back to the heavens where it had initially come from. I know exactly where to find that. I need only gaze up and see its shadow in the stars.

But the rakusu from my precepts ceremony, that little robe, the first robe, is lost.

Perhaps, when I finally answer the question, the ever-elusive one that inspires Zen practice, perhaps then my little friend will reappear. But until then, my lost robe will remain just that. Lost.

I am quite content about it. I have no regrets. I continue to love my teachers unconditionally. And I miss my friends. And my little robe? Like a little lamb who strayed a step or two too far, it is somewhere, unaware of its lostness, waiting to be found, and brought home.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.