It was a crisp Sunday morning in late January. I stood with a group of pilgrims lined up before a village shrine at the base of Mount Ontake. Our white robes pressed down fleeces and bulky jackets that threatened to spill out from their cotton sleeves. Suddenly, we were ordered to prostrate and bow our heads to the ground. I felt grateful to have worn ski pants as I rested my knees on a footpath of uneven cobblestone and snow. A shrill voice pierced the air, and we listened with rapt attention. This was the first oracle of the day.

The group comprised young men and women, couples, friends, and elders. We shared deep bonds forged out of neighborhood parish gatherings, chartered bus rides to Ontake, and strenuous ascents up the mountain. This and other séances over the course of the day would provide us with close encounters with Buddhist divinities and departed loved ones. Having left behind our ordinary lives in the metropolis of Nagoya, we were assembled here for another day of shared miracles on one of Japan’s most sacred peaks.

Oracle and séance are not rituals that readily align with modern notions of Buddhist practice. Those notions, however, were conceived by 19th-century intellectuals, many outside the tradition, who put forth a narrow vision of the Buddhist path. Amidst the harsh environment of a winter mountain, the pilgrims in this group were proving just how narrow that vision is.

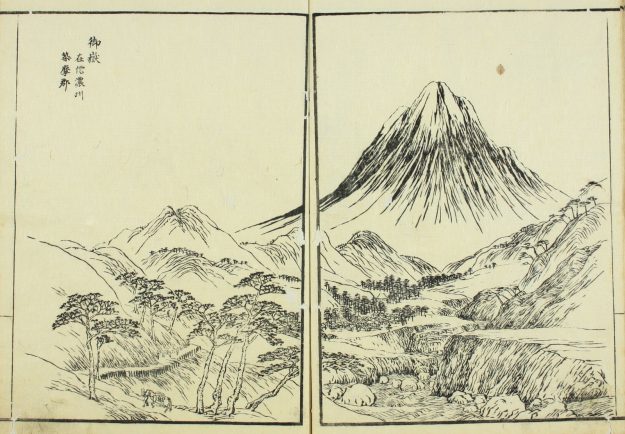

Rising above 10,000 feet at the southern end of Japan’s Central Alps, Mount Ontake is massive in terms of elevation and surface area. It is also an active volcano, a trait that hikers and devotees were tragically reminded of when a deadly eruption killed sixty-three people there on September 27, 2014. It would take several years before pilgrims felt safe returning to the mountain.

But today’s group had been visiting the mountain long before the eruption. While some members had recently joined, others were carrying on a tradition that stretched back generations in their families. Today had begun with quiet, individual prayers at Shusshō Motogumi, the group’s temple in Nagoya, shortly before 7 a.m. Boarding a chartered bus, we journeyed several hours along highways and roads that eventually led us along a broad river valley rising into the mountains.

The first dramatic event I witnessed that morning occurred at the village of Satomiya, which serves as the traditional entrance to the Ontake massif. In this familiar ritual, a lead guide acts as a vessel for a deceased visiting spirit or mountain deity, and an assisting guide orchestrates the encounter to ensure the safety of the spirit medium. On this particular occasion, the mythological Shinto deities Izanagi and Izanami entered the body of our lead guide. They welcomed us and noted that the weather would be calm for the day. Assisting guides performed rapid-fire mudra signs, dialogued with the visiting deities, offered saké, and instructed us on when to prostrate, rise, and so forth. Throughout this séance, our lead guide stood bolt upright and held a festooned paper wand (gohei) in front of his face to conceal the deities from the human world.

Witnessing the presence of the divine, everyone in the group bowed and listened intently. The encounter seemed to take us out of our mundane reality and into intimate proximity with the sacred. After the deities’ farewell and the medium’s return to consciousness, life resumed. Jokes, banter, smartphone selfies, and stumbles across an icy road back to the bus.

The next event was equally dramatic, if not harrowing. Above the road were narrow steps leading to a waterfall flowing through curtains of ice. Our lead guide stripped down to a loin cloth and submerged himself under the waterfall, a regular practice in Japanese pilgrimage but not so common in the dead of winter. As one element in a regiment of ascetic cultivation (shugyō), it is intended to purify and align the practitioner with the gods (in this case, the wrathful Fudō Myōō, known in India as Acala).

As our guide locked hands in prayer, the group vigorously chanted the Heart Sutra and other incantations to ensure his protection. Afterward, he was embraced with towels and escorted to an outdoor changing stall.

Lunch was followed by an ascent up snow-laden steps to a cluster of memorial stones. The lower slopes of Ontake are populated by thousands of tall memorial stones dedicated to the spirits (reijin) of former guides. They provide a contact zone for meetings between the living and the dead, or in Japanese, this realm and that realm. As we gathered around one stone and adorned it with flowers and photos of a deceased member, a séance began. In an instant of transformation, our lead guide was washed over by the gentle voice and mannerisms of one of their departed guides. She came in kindred spirit, delivering messages and counsel to dear friends. Some wept, others smiled in reassurance. A few laughs erupted when she offered a word of welcome to the visiting foreigner (“Gaijin-san”). An assisting guide discreetly whispered an introduction into our lead guide’s ear to acquaint us.

Ontake has a long history of Buddhist itinerants frequenting its slopes to perform ascetic rituals, including seclusion and fasting, chants under waterfalls, and prayers to the mountain’s pantheon of buddhas and local gods. Ordinary pilgrims did not venture up its higher reaches until two ascetics guided their followers up the mountain in the late 18th century: Kakumei (1718–1786), traveling from the Kansai region in 1784, and Fukan (1731–1801), arriving from Kantō in 1794. Generations of pilgrims have since traced their roots back to them. Over time, they formed pilgrimage associations that collectively worshiped the mountain and its resident deities. Under the leadership of pilgrimage guides (sendatsu), they conducted services at neighborhood temples and on the mountain. It is important to note, here, though, that women were historically barred from climbing many sacred peaks, including Ontake, as misogynistic discourse over notions of female impurity led to fears of invoking the mountain gods’ wrath should they enter. Although the government banned these restrictions in 1872, ideas about impurity, especially menstruation, continue to surface, and religious institutions remain androcentric.

Worship at Ontake has typically blended Buddhism, Shinto, and Shugendō (Japan’s premier mountain-based tradition). Ascetic priests and itinerants historically performed services on behalf of various deities and spirits centered on appeasement, gratitude, and teachings of the Buddha. They prayed to divine embodiments of the natural world (boulders, waterfalls, trees, mountains), ancestral spirits, numinous dragons, and even vengeful ghosts (who required pacification). In doing so, they brought local deities and those who worshiped them into the Buddhist worldview.

Local mountain deities were believed to dwell in symbiosis with the Mahayana pantheon of awakened buddhas and bodhisattvas. Collectively, they provided water to the plains below via the mountain streams, and when summoned by the spiritually advanced, they granted mountain priests heightened abilities in divination, healing, and merit accumulation. As pilgrimage to sacred peaks became widespread in the 18th century, more and more people ventured to higher elevations to meet and pray to the divinities themselves.

Then, religious sites in Japan underwent a radical transformation in the late 19th century. The Meiji government (1868–1912) promulgated the separation of Buddhism and Shinto in 1868, a policy that had sweeping effects on religious communities nationwide. In response, the Ontake pilgrimage associations nominally became Shinto organizations, but this did not stop them from engaging in Buddhist practices and beliefs. In their parish temples and on the mountain, they continued to invoke buddhas and bodhisattvas in prayer, chant sutras, perform mudras, and wear prayer beads. In the subsequent century and a half, pilgrimage continues to encompass elements of Buddhism and Shinto. Because neither tradition is maintained by a strong sense of personal, communal, or institutional identity, the majority of practitioners do not see this type of synthesis as problematic.

In the early 20th century, the Ontake pilgrimage rivaled that of any other mountain in Japan, including Mount Fuji, drawing tens of thousands of pilgrims from Tokyo, Yokohama, Osaka, Nagoya, and beyond every summer. That said, annual government survey statistics reveal a long-term decline since at least the 1970s, which can be attributed to the country’s aging population, occupational shifts away from self-employment and small businesses (operated by many devotees), and disrupted community and family networks as younger generations gravitate from towns and villages toward the major cities.

My introduction to Ontake worship had come from vivid, if not unsettling, accounts dating back to the late 19th century. As visitors from Europe and the United States landed on Japanese soil with increasing frequency, some chronicled their explorations for a Western readership captivated by the Far East. These impressions provided illuminating windows into Japanese ritual life but, at the same time, eerily placed their subjects in realms of the exotic and nonmodern. The Bostonian businessman, author, and astronomer Percival Lowell began his famous book Occult Japan: or The Way of the Gods, an Esoteric Study of Japanese Personality and Possession (1894) with a description of a “strange” and “ungodly” séance on the summit of Ontake. He summed it up in sweeping fashion: “There proved to exist a regular system of divine possession, an esoteric cult imbedded in the very heart and core of the Japanese character and instinct, with all the strangeness of that to us enigmatical race.”

Two years later, Walter Weston, a British Anglican minister celebrated as the founder of modern alpinism in Japan, offered another account. While many of his writings portray mountain worship in Japan in respectful terms, he, too, mused on the “weirdness” of a series of Buddhist mudras performed on Ontake in a similar séance: “Each twist, each knot, has its own meaning, and resembles a sort of dumb alphabet, spoken with all the expression that physical action can put into it. For language it is really meant to be addressed to those invisible powers of evil against whose malevolence the pilgrim is appealing for protection.” At first glance, the accounts of Lowell and Weston reflect a sense of cultural superiority and Orientalism common at the time. On a deeper level, however, they represent formative ideas about what constitutes acceptable forms of religious faith and what gets excluded.

Defining religion as a distinct component of the human experience, 19th-century Western intellectuals naturally drew from their Protestant values and Enlightenment ideals, privileging textual authority over lived religion, belief over ritual, and spirituality over materiality. Popular practices outside formal institutions—divinations, exorcisms, and séances like the ones on Mount Ontake—were deemed superstitious and needed to be expunged from religion.

Under this thinking, theologians like Edwin Arnold, Henry Olcott, and Paul Carus attempted to “correct” contemporary Asian Buddhism, promoting their vision of a rational, ethical, and scientific tradition at its core. In Japan, interlocutors like the cosmopolitan Zen priest Shaku Sōen joined this movement at events like the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893. As scholar Donald Lopez puts it, there was no place for superstition and unenlightened behavior in this new convergence of Buddhism and science.

Protestant Buddhism and its paternalistic impulses do not die quickly. Nor does its bedfellow, Orientalism. And long after the dismissive remarks of 19th-century visitors to Japan, there has still been little attempt to understand the ritual life of Ontake pilgrimage. As I witnessed on Ontake firsthand, however, these practices and the surrounding communities reveal a broader, more inclusive scope of how we might understand the Buddhist path.

The culmination of the Sunday in January came at a goma temple in a series of powerful rituals. The goma is an empowering fire ritual that traces back to ancient India, where it was adopted into Buddhism. Our lead guide, taking bundles of wooden sticks purchased by parishioners and dedicated to themselves and their loved ones, sat cross-legged before the altar and built a lurching Jenga-like tower that rose to his eye level. Flames spiraled into the air, higher with each successive build, licking the ventilation shaft in the ceiling. On two occasions, flaming sticks pitched off the tower and dropped onto his lap and between his seat and the altar. Smoke encircled the room as the group vigorously chanted sutras and mantras, rattled bells, and blew conch-shell trumpets to help control the fire while enhancing its efficacious benefits. One parishioner collected our prayer beads so he could wave them through the fire, purifying and emblazing them with healing powers that we could rub onto aching limbs and joints.

As the fire dimmed, all fell quiet. A deity had once again taken over the body and voice of our guide. Springing from the seat cushion in a deft 180-degree turn, Nyoirin Kannon faced us and announced her presence. Typically female in Japan, Nyoirin is one form of the bodhisattva Kannon (Ch. Guanyin, Skt. Avalokiteshvara). She is especially popular among women and parents for fertility, childbirth, and healthy children. Embodying her, our guide sank into the form of a tender, feminine figure gracing the room with her divine presence. All leaned forward in quiet anticipation.

We were tapped to line up to commune with Nyoirin Kannon one at a time. She spoke to each person with the compassion emblematic of a loving bodhisattva. Each encounter brought an intimate exchange of soothing whispers, healing rubs to arms and thighs, and responding nods of recognition and gratitude. As a participant observer, I felt somewhat uneasy when called forward myself. I politely nodded through most of her counsel, yet was taken off guard when she informed me of my grandmother’s presence by our side. Nyoirin’s departure was sad and protracted, like a parent saying goodbye to a child. She thanked me for making the trip from Fukuoka and invited me to return for the group’s summer ascent of Ontake.

I reflected on the day on my return home. Its events were not simply empty rituals passed down from the previous generation and now upheld out of familial obligation. They did not feel like superstitious forays into the strange and exotic, as earlier Western intellectuals would have us believe. Instead, this brief Sunday pilgrimage conferred simple, if not powerful, touchstones of joy. The chance to reconnect with a departed loved one, to pray for an auspicious year, to be surrounded by a caring community, to share a delicious meal—as well as several gifts rare in this world—visits from distant deities, healing hands, and for a few, the ability to host spirits of the divine in their bodies.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.