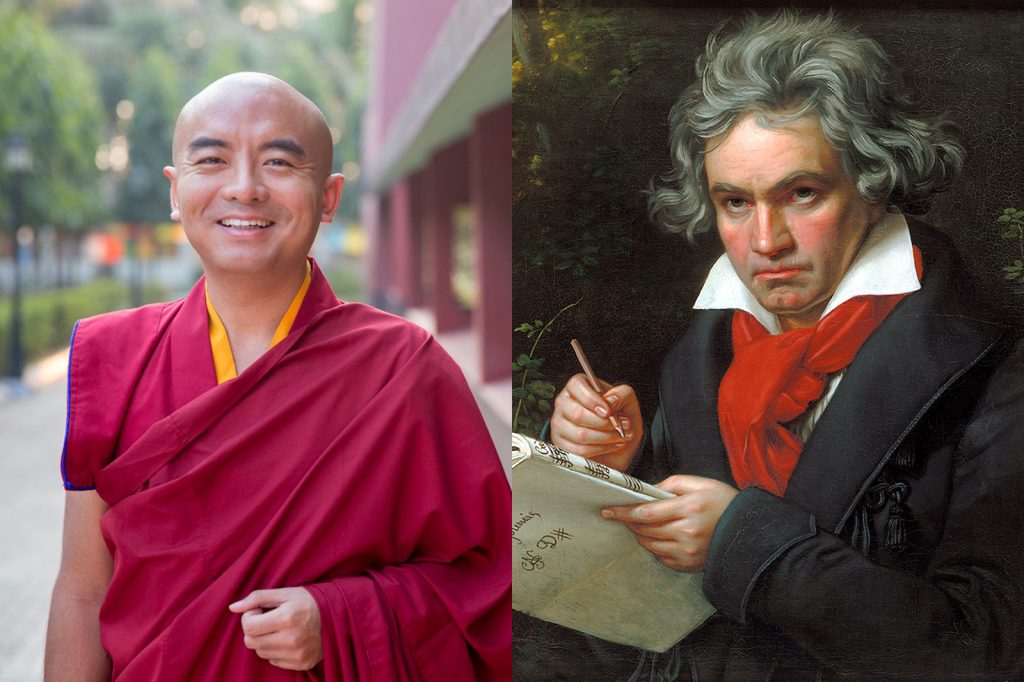

In many listening meditations, practitioners observe whatever sounds happen to arise around them, a method that has the benefit of being at our disposal anytime and anywhere. But the same concept can be applied when listening to music, according to Tibetan Buddhist teacher Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche. In a demonstration with a live orchestra, Mingyur Rinpoche explains how to listen mindfully to classical music as a method of observing our emotions.

By meditating on the compositions of Sergei Rachmaninoff, Ludwig van Beethoven, and others, we can observe the wide range of emotions that these works evoke in us. As Mingyur Rinpoche explains, when we direct our awareness toward these emotions, they lose their power over us. In this way, we can learn to notice these feelings without rejecting or being beholden to them.

The following is an excerpt of Mingyur Rinpoche’s instruction for listening meditation from the film Union of Sound and Emptiness as well as the full video of the live performance, courtesy of the Tergar Meditation Community.

***

How do you practice listening meditation? Just listen to sound. If you know that you are listening to sound, that is meditation. Normally you don’t know that you are listening because your mind is lost in the sound. But when you do know, your mind is not lost. In this way, you can enjoy music and meditate at the same time.

You do not need to worry if you have extra awareness about whether or not you are listening. Don’t check too much. Just listen with your ear and mind together. The sound and the music become the object of the meditation. That is good for the crazy monkey mind because you are giving it a job. Normally the monkey mind gives us jobs, but when you give the monkey mind a job, then you become the boss.

Here’s how to practice: First, relax the muscles in your body, and try to keep your spine straight. Relax and let go of all your worry. Just be your mind in your body; your mind comes to your body, fills your body. And just relax as though you just finished a physical exercise—sit in your comfortable chair with a big sigh, a big breath.

From this relaxed posture, begin listening to sound. Don’t listen too forcefully; simply notice the sound.

You cannot mindfully listen to sound for too long, maybe a few seconds, before your mind wanders away. That’s OK. Listen again. The practice consists of a short time, many times.

You will notice that you have a lot of thoughts and emotions, which is the crazy monkey mind. But the monkey mind is not a problem. The problem is in how you are treating it. We tend to treat the monkey mind in two ways. In the first way, you are listening to the monkey mind and believe what it has to say—if the monkey mind says, “No good,” you believe it is not good. That leads to anger, fear, jealousy, panic, and so on.

In the second way, you hate the monkey mind, you fight with the monkey mind. If you have anger, you are fighting with the anger. But you cannot defeat anger by fighting it. If you fight with the monkey mind, it becomes your enemy. Yet if you listen to the monkey mind, it becomes your boss.

So what do you do?

Instead of telling the thought or emotion, “Get out!” or “Yes, sir,” you just let go, and give a job to the monkey mind.

When I was young I had panic attacks, which was a great source of suffering. But then I learned meditation, and I made friends with my panic. I ended up becoming very grateful to my panic because it is why I am here—to share my experience.

So, as you listen to this music, be aware of your emotions in the same way that you are aware of the sound. Your mind can go back and forth between listening to the music and being aware of the feelings that arise in your body. This awareness of emotion is like the sun, which eliminates darkness. When you are aware of the emotion, it becomes powerless.

See the full video from Union of Sound and Emptiness here.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.