I was always working steady

But I never called it art

I was funding my depression

Meeting Jesus reading Marx

Sure it failed my little fire

But it’s bright the dying spark

Go tell the young messiah

What happens to the heart—“Happens To The Heart,” The Flame

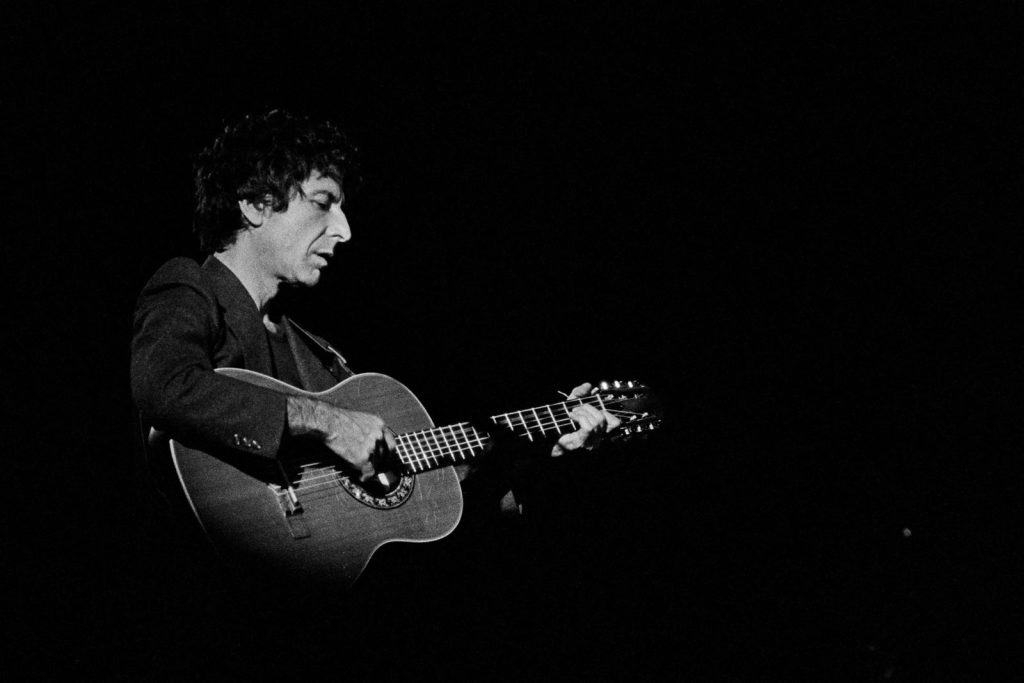

October saw the arrival of two treats for fans of the late Leonard Cohen. The first, Matters of Vital Interest: A Forty-Year Friendship with Leonard Cohen, is written by Cohen’s long-term friend and fellow Zen student Eric Lerner. The second, The Flame, is a posthumous collection of Cohen’s poems, late songs, and notebook fragments curated by his son, Adam. Both books are chronicles of Cohen’s struggles with the life of art and the art of life. And they are shot through with his perennial themes—darkness and light, spirit and flesh, love and despair, and failure and acceptance.

Lerner, early on in Matters of Vital Interest, recounts the time he asked Leonard if he’d ever read the American philosopher William James’ The Varieties of Religious Experience, in which two kinds of religious people are outlined: “the healthy-minded, who need to be born only once, and the sick souls who must be twice-born in order to be happy.” The healthy-minded go in for religious paths of optimism and worldliness that affirm life as good, while the sick souls see life as suffering and a problem to be solved.

“That’s not a bad description of IT,” replied Cohen. IT was Cohen and Lerner’s name for the problem that haunted both of them—the sense that the things of this life offered only a temporary, deceptive refuge, and that there was something beyond, something more real that they desired even though they could not name or meet it. A divine discontent united them. Matters of Vital Interest follows Cohen and Lerner’s 40-year pursuit of a solution to IT, often in the circle of the Zen master they shared, Joshu Sasaki Roshi (1907–2014).

Lerner’s telling of their friendship is funny and revealing, written in his evocative, easy prose. Lerner pulls off the stunt of being self-deprecating while also bringing to life the swaggering, tongue-in-cheek bravado and hard-won wisdom that the two Jewish Buddhists shared with each other like a fine cognac (something they also shared with each other not infrequently).

Lerner depicts the two as holy rascals with their heads in the clouds of divinity while struggling with the world of family and career. Although both Cohen and Lerner clearly revere the women in their life, their conversations often circle back around to an expressed desire to freely pursue both sex and spirituality while seeing themselves as trapped by their domestic loves and duties. For this reason, many women—and men—may find parts of the book hard to read. As Lerner tells it, he and Cohen at times veer between grating escapism and locker-room conversation. On the other hand, Lerner’s unflinching honesty in this and other matters is often refreshing.

For most of us who only know the late Cohen’s public persona as a gentleman poet, secular saint, retired ladies man, and self-deprecating elder statesman of the arts, Lerner’s book unveils a messier picture of Cohen the human being. Matters is remarkable for its gritty depiction of both Cohen the hustling, sly, broken survivalist, and Cohen the tender, present, and devoted father of two children who once told Lerner he would be happy if his tombstone simply read “Father.”

In the end, the book becomes a heartbreaking evocation of Lerner and Cohen’s friendship as they face down the harrowing debilities of old age, chronic pain, prescription drugs, and Cohen’s deterioration from leukemia. The two trade barbs, witticisms, and comforts by email all the way, right up until moments before Cohen’s death. Cohen had fallen during the night, and wrote Lerner afterwards of how sweet it was to be back in bed again, hit by “waves of sweetness that felt overwhelming.” Lerner emailed his friend back several times hoping for a response that never came.

Lerner and Cohen viewed their longtime Zen master, the iconoclastic and irreverent Sasaki Roshi, as an enigma to wrestle with together. Matters of Vital Interest opens a candid window on the two men’s relationship with Sasaki, who Cohen, the more consistent and serious disciple of the two, remained deeply dedicated to years after he no longer idealized Sasaki as an enlightened master. Cohen, who spent years as Sasaki Roshi’s personal cook and was an ordained monk at the Mt. Baldy Zen Center in California for five years in the 1990s, always characterized his relationship with him as a deep friendship.

Sasaki Roshi’s final years, however, were marred by allegations that he had engaged in inappropriate sexual behavior with many disciples and nuns, including acts of molestation and coerced sexual contact. Cohen, who rarely publicly criticized anyone or acted as a moralist, had been mostly silent about his friend’s sexual behaviour, even though he had known that the married Sasaki had slept with several female disciples at the monastery (it appears Cohen was not aware of the severity of Sasaki’s behavior until later, though this is unclear). According to Lerner, both he and Cohen eventually saw through Sasaki’s egotism and mind games, and Cohen had no illusions about him in his later years. By the time the scandal broke in 2013 and the full scope of the misconduct became known to Cohen and others—Cohen followed the online revelations closely—Sasaki Roshi was 105 and quite ill. Cohen, who was in charge of the deteriorating Roshi’s medical care, did not speak publicly about it.

A rare exception to Cohen’s silence about the scandal occurs in a poem in The Flame. In one of series of three poems about his teacher, Cohen writes:

During Roshi’s sex scandal (he was 105) my association with Roshi was often mentioned in the newspaper reports.

Roshi said:

I give you lots of trouble.I said:

Yes, Roshi, you give me lots of trouble.Roshi said:

I should die.I said:

It won’t help.Roshi didn’t laugh.

Readers will be left to contemplate Cohen’s refusal to become his friend’s public adversary or critic for themselves.

The strongest new material in The Flame are the poems that make up the first part of the book. These range over the themes of love, failure, yearning, the nature of reality, and the dangerous precipices of the heart. They are filled with the irony and beauty one would expect and contain many searing images and confessions, as well a fair bit of deadpan humor. One poem that has attracted a lot of attention on social media jokingly spars with Kanye West and Jay-Z, asserting, in a parody of everyone involved, that “Jay-Z is not the Dylan of anything/ I am the Dylan of anything/ I am the Kanye West of Kanye West/ The Kanye West/ Of the great bogus shift of bullshit culture/ from one boutique to another.” Another tells of a beautiful morning out shopping with his then-lover Anjani Thomas, detailing the patina of delight he saw over every mundane detail, then concluding, “I am so grateful for my new antidepressants.”

The sacred scriptures of Judaism, which Cohen knew well, say that just as the exodus from Egypt took place at midnight, so the final redemption of the world will also take place “by means of midnight”—in other words, by those who can find the sparks of light in the midst of the darkness of despair, dislocation, loss, and failure. Or to put it another way, “There is a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.”

That famous quote comes from Anthem, a Kabbalistic song-poem of Cohen’s, whose spirituality was deeply informed by Jewish mysticism as well as Zen. Cohen, who struggled for years with clinical anxiety and depression, was by necessity a master of finding the thread of light in the darkness. Cohen saw through human pretensions, including his own—yet he viewed it all with an animating mercy, which made people want to draw close to his person and his art. His steely gaze and his tender heart are amply on display in these new releases, both of which also offer many gems for those who share Cohen’s curious fascination with matters of the spirit. One brief verse from The Flame serves as a fitting thread to tie both books together:

tho’ mercy has no point of view

and no one’s here to suffer

we cry aloud, as humans do:

we cry to one another.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.