Over the course of my relatively brief stint as a Buddhist inquirer, I’ve had the privilege of experiencing the fresh insight—and occasionally dull redundancy—of several introductions to meditation. The arc always goes something like this:

Over the course of my relatively brief stint as a Buddhist inquirer, I’ve had the privilege of experiencing the fresh insight—and occasionally dull redundancy—of several introductions to meditation. The arc always goes something like this:

First, we talk posture. This is when the flexible caste pretzels into full lotus while the teacher kindly points out the row of folding chairs lining the back wall. Then, we trudge through a survey of different meditation styles, culminating in the particular workshop’s focus. Here, oftentimes, is when we get down and dirty with some meditation—maybe five minutes or 20, usually with a practitioner’s supportive parent succumbing to a nap midway. A debrief ensues, followed closely by discussion of how to establish a regular routine.

Finally, there’s the caveat. This caveat happens every single time, without fail. Whether in a Zen center in upstate New York or a Theravada temple in Thailand, I’ve always heard it. The caveat is that we do not practice meditation for its own sake, but for enriching our lives and those of others. The goal is not to win the Meditation Practitioners Guild award for Best Attention to Breath; it’s to bring our newfound awareness off the cushion and into the nitty-gritty stuff of living.

Mostly, I like this sentiment. It adds a dose of humility to a somewhat glamorizing affair. And it tethers us back to the anchor of intention: why we’ve come to this technique and why we should keep it up. The more lucid and honest our motivation, the more likely we are to value our practice. The caveat undoubtedly helps us avoid the slide from introspection to solipsism, which our culture otherwise constantly reaffirms.

Lately, though, I’ve grown circumspect about the caveat’s naïve promise. It implies that each and every facet of our lives is equally ripe for extending the practice. In a literal sense, of course, this is true. So long as our practice entails following our breath or bodily sensations, we can access this attentiveness in any circumstances. Yet the apparently limitless opportunity is misleading. Surely some activities are far more conducive to retaining mindfulness than others, and we best seek them out.

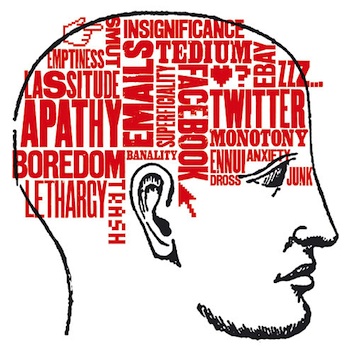

Not only that, but it seems some activities entirely foreclose the opportunity for this kind of attention. One, in particular, involves a technological advance that has crept from our office to our living room to our pocket, and finally—if Google has its way—to our very eyeballs. I’m talking, of course, about the Internet. In his staggering work, The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains, Nicholas Carr argues convincingly for the inherent rewiring of our brains and alteration of our consciousness that occurs by virtue (or vice) of our using the web. His barrage of evidence vindicates the 1960s scholar Marshall McLuhan, who famously pronounced, “The medium is the message.” There is no way to completely mitigate the mind-scrambling effects of the Internet. No way.

We live in a new normal, as the environmentalists like to say. And it doesn’t feel hyperbolic to compare the pervasiveness of digital content to that of weather patterns. It would prove just about impossible to conduct my life without the Internet, not to mention a whole lot less fun. Who’s watching season two of House of Cards? It’s nuts.

So we’re stuck. This is probably why we don’t speak very much about the Internet’s effect on our psyche. It’s uncouth, moot. The Internet has won the war. But let’s at least not deceive ourselves about the casualties.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.