For months members of the House of Representatives wrangled over how much in cuts they would make to the nation’s food stamps program in the new Farm Bill they were drafting. On July 11, by a vote of 216 to 208, the House finally passed a bill, and guess what? The bill does not include any funding for food stamps. Opposition to the bill was strong—all Democrats joined by twelve Republicans voted against it—but the majority prevailed, reflecting the agenda of Tea Party ideologues and conservative deficit hawks who dominate in the House.

The vote does not mean that food stamps are about to be consigned to the dust bin of history. The House version of the bill still has to be reconciled with the Senate version, which includes allocations for food stamps, and the White House has said President Obama would veto any bill that drops food aid. Republicans have tried to mollify opposition with a promise to draft a separate food stamp bill in the near future, and even some advocates for hunger relief applaud the separation of food aid from subsidies for Big Agribusiness.

The Senate version of the Farm Bill, passed with bipartisan support in June, is far from benign, cutting expenditures on food stamps by $4 billion over the next decade. A cut even of this size moves the country in a direction opposite from where we need to be moving. But even more worrisome is the pugnacious attitude in the House, which raises suspicions that conservatives are keen on reducing SNAP—the food stamps program—to little more than a pale image of its former self. The Republican bill proposed last month, which went down in defeat, would have slashed funding for SNAP by $20.5 billion over a ten-year period. With deficit hawks and rural conservatives united against government spending, there are reasons to fear they will try to push through cuts as drastic as they can get away with.

The ultimate future of food stamps is now clouded in uncertainty, but I’m not concerned with the issue from a political perspective, where the focus is on using the right tactics and issuing the right sound bites to triumph in the struggle for power. I look at the contention in ethical terms, as presenting us with a choice about the fundamental premises that define our sense of collective identity. Given that government, in theory at least, is our common will, representing us as a people, how do we define ourselves? Will we come to the aid of those among us struggling to get by or will we throw the needy back upon their own meager resources? Is the prevailing philosophy of governance one of mutual concern and collective help, or one of stark individualism in which everyone has to fend for themselves, or at best rely on charity? This is not so much a political question as a moral one, a question pertaining to the moral basis of our common life. Much depends on how we answer it.

When the question is addressed from a moral point of view, one thing is clear: the combined voices of compassion and social justice decree that we give those in need a helping hand, not a hand that takes away the raft keeping them afloat. Today millions of Americans are struggling to get by in an inert economy hit hard by persistently high unemployment and debilitating poverty. Forty-eight million people depend on food stamps, among them the long-term unemployed, elderly people, single mothers, and children both in the urban jungles and rural back country. Six million folks have no other source of income but food stamps. Fast-food workers, service sector employees, and other manual workers are paid a minimum wage that is far too minimal even to support a child. If we’re really serious about fulfilling the promise of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” extolled by our Founding Fathers, we must begin by ensuring that people can eat properly. While it’s best that those in the prime of life work at jobs paying decent wages that will enable them to buy their own healthy and nutritious foods, for those cast down through no fault of their own, what is needed is more nutritional assistance, not less.

Moreover, it can’t be argued that shortfalls in public food assistance can be made good by private charity, that the poor can turn for help to religious and secular organizations devoted to helping the hungry. The plain fact is that the amount of funding required to provide nutritional assistance on the scale we face today exponentially exceeds that available through private charities. The only collective body that can address such demand is the government. It’s thus up to our representatives to decide where they stand: whether they will offer the hungry and undernourished a helping hand, or withdraw their help and offer empty plates and hollow platitudes about hard work and personal responsibility.

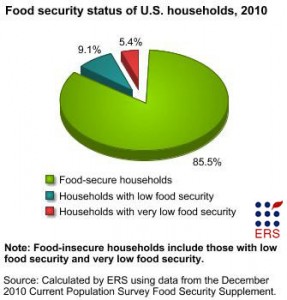

Just a few weeks before the vote on the Farm Bill, I read a report entitled Nourishing Change: Fulfilling the Right to Food in the United States, published earlier this year by the International Human Rights Clinic at New York University’s School of Law. The report underscores the hard truth that the U.S. is facing a food security crisis of immense proportions. Food insecurity affects 50 million people—one American out of six—including nearly 17 million children. Of the 50 million, 17 million live in households described as “very low food security,” defined as a condition where people often have to skip meals or subsist on snacks, where they struggle with hard choices between buying food or paying for medical care, rent, and heating.

The report, which is concise and clear and well worth reading in its entirety, points out that food insecurity is not the result of a shortage of food. It’s the result of poverty, and of policies that fail to prioritize the needs of low-income Americans. Moreover, the report contends, government policies over the past decade have weakened the social safety net, subtly chipping away at programs that showed the country at its most compassionate. Even the benefits given under SNAP hardly suffice to provide its beneficiaries with adequate nutrition. Food stamps offer less than $2 per meal for each person in a household. To stretch these funds, families usually purchase cheap junk food—high in calories but low in nutritional value—over healthful fruits and vegetables. If government spending on food stamps shrinks on account of the new bill, dependent families will inevitably be pushed ever closer to the abyss of desperation.

Rather than see food assistance as an act of charity on the part of the government, the report argues for a different approach that regards adequate food as a human right. This is essentially the same position endorsed in a paper by BGR Board member Charles Elliott on the “right to food” as a fundamental human right. From this standpoint, people are recognized not simply as recipients of charity but as holders of rights. And since rights imply duties, to adopt this standpoint is to treat governments as duty bearers, responsible for ensuring that all people under their jurisdiction can realize their right to safe and nutritious food (p. 24). Respecting the right to food entails an obligation to develop policies and programs that empower people to feed themselves and their families. But, the report argues, when people are unable to obtain food for themselves, the government must implement effective social programs that directly provide adequate food to those in need.

Applying the human rights framework to the issue of food security “shifts the focus from individual or private efforts to the government’s responsibility to ensure that people are actually empowered to provide for themselves and their families. The rights-based approach to food demands accountability from duty bearers for failures to fulfill the obligations described above” (p. 25). At present, when the economic downturn that began in 2008 has cast millions of people into chronic unemployment, and when neoliberal theory exhorts employers to downsize, shift their operations overseas, and scale back salaries and benefits for their employees, a human rights approach to food security becomes especially timely.

But while the human rights approach is relevant to food assistance, its ramifications go much further, extending to almost every aspect of public policy. Besides nutrition, it has implications for taxation, health care, energy, education, and the environment. A human rights approach gives precedence to the moral point of view, and thus counters the tendency of market fundamentalism to provide the corporate elite with a rationale for appropriating ever more wealth for themselves. The human rights approach recognizes all people as essentially equal in their fundamental needs and thus as entitled to the material and social requisites of a dignified human life.

Taking the moral standpoint means that in deciding how to act, we must place ourselves in the position of those who will be affected by our actions and then make our decisions by considering how we would feel if we were in their place. This virtually turns moral reflection into an exercise in meditation, the overlap between the two being especially evident in the meditations on lovingkindness and compassion. In the meditation on lovingkindness, we project ourselves imaginatively into the position of others—traditionally, the respected person, the dear person, the mere acquaintance, the stranger, and the hostile person—wishing for each the same degree of well-being and happiness we wish for ourselves. In the meditation on compassion, we bring to mind people afflicted with suffering, imagining we are in their place and generating the wish that they be free from suffering. Moral reflection and the meditations on lovingkindness and compassion thus inform and shape each other. Both call into play the ethical imagination. Both require that we rise up above our entrenched private point of view and act on the basis of an impartial, panoramic perspective on the maximum good achievable for others and ourselves.

Together, moral reflection and meditative contemplation give us grounds for holding that government is obliged to fulfill the basic needs of the vulnerable among us. This is particularly the case with regard to food, housing, and medical care. If we push hard on the human rights approach, enacting cuts to SNAP becomes not only heartless but a breach of duty subject to moral reproach.

Adopting this orientation leads to a very different outlook from that of neoliberal theory, which subordinates moral considerations to those of competitive expediency. Whereas neoliberal theory encourages stark individualism, human rights theory advocates a sense of humane responsibility. It holds that we are inextricably bound together in a community in which we all depend on one another and in which the welfare of each depends on the well-being of all. Whereas the most prized personal assets in neoliberal theory are strength, ambition, cunning, and competitive zeal, human rights theory gives precedence to care, compassion, and cooperation.

Whereas neoliberal theory sees us as intrinsically engaged in a brute struggle in which we must each seek to prevail over others, a human rights approach implies that we have duties to others, with government functioning as our collective organ in fulfilling these duties. Thus, the human rights approach says that government has a role to play in establishing communal welfare. Rather than standing on the sidelines and letting market forces determine the fate of persons in a drifting sea of private interests, government must provide a life boat. At minimum this means it must ensure that no one is crushed by the blows of a harshly competitive economy.

These two theories are not merely theoretical but the springs of two very different attitudes to life. They have very real, very “hard,” impacts in the real world, on the formulation of policies and in the way societies are governed. In their differences they hang before us, demanding that we choose between them. The fate of our civilization, for good or for harm, will almost certainly depend on the choice we make.

Further Reading

Into the Fire: Food in the Age of Climate Change

The Attack at Home: A new bill threatens the food security of millions

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.