Don’t look at Zen art. You will miss much of the richness of the experience. Instead, join the artist in as many ways as you can, with as many senses as you can.

Over my decades of training in Rinzai Zen, shodo (Zen calligraphy), and firing ceramics with wood, I have come to realize that the full experience of Zen art involves collapsing the distinction between art and viewer. But to understand how this can happen, it’s important to first know how Zen art is made and how its artists train to express their attainment through their works.

The Energy of Zen Art

In much of Japanese culture, sight is considered to be the least reliable of the senses. Japanese art, and especially Zen art, is not meant to be a visual experience. Miyamoto Musashi, a master Japanese swordsman and artist of the 17th century, said, “The eye of intuition is strong; the eye of vision is weak.” In other words, what matters most in life are not the visible forms seen by the eye but that which is perceived by a deep spiritual intuition. And that which is perceived is a spiritual force or vital energy called kiai.

In the masterpieces of calligraphy in Japan and China, this energy is called bokki, the “kiai of the ink.” By extension, for ceramics, my Zen teacher, Tenshin Tanouye Roshi, called this vital energy dokki, the “kiai of the earth.”

For the ink to have this force, the person who drew the calligraphy must have a strong spiritual foundation. Or, in terms of our style of Zen training, a highly developed use of breath and posture. Calligraphy and ceramics with such kiai have the power to move those who encounter them.

For example, many years ago I was a docent for an art show at Chozen-ji that featured ceramics thrown by a master potter who is also a Zen master. At one point I noticed a man standing in front of one of her pieces, a big vase on a pedestal at about waist height. Over the course of about 15 seconds, I saw the profile of his torso and abdomen shift in a way that ended up matching the profile of the vase. The same curvature, the same proportions, the same feeling of groundedness. He became the vase. Then he walked away, and his profile returned to its previous shape.

That vase would be said to have kiai.

To better understand bokki and dokki, consider the name of the school of calligraphy used for training within the Chozen-ji lineage of Rinzai Zen. The name—Jubokudo in Japanese—means “deep in the wood” and comes from a story about a work of calligraphy that the 4th-century Chinese calligrapher Wang Hsi-chi had brushed on a plank of wood.

A man found the calligraphy some time later and, not recognizing its value, began shaving down the plank to erase the ink and create a fresh surface for writing. No matter how deeply he cut, however, the ink went deeper into the wood. This “deeper,” when expressed with ink, is bokki and, when expressed in clay, is dokki.

How are these vital energies cultivated? Through years of Zen training.

Training in Zen Art

In the calligraphy courses offered at Spring Green Zen Dojo in Wisconsin, where I am head priest, our line of Jubokudo comes through Yamaoka Tesshu, a noted swordsman, statesman, and lay Zen master of 19th-century Japan. He created a calligraphy manual based on the 154 Chinese characters of a poem, “The Eight Immortals of the Wine Cup,” by the Tang Dynasty poet Tu Fu. The story goes that Tesshu picked this poem as the basis of a calligraphy manual he made for his wife when she asked to learn the craft.

We start by grounding our breath and posture, following the training methods developed by the 20th-century swordsman, calligrapher, and Zen master Omori Roshi, as we draw a diagonal line with as much concentration as possible. We then train through imitation, brushing characters as shown in Tesshu’s manual, three characters at a time.

The weight of the brush can help ground the piece. The work of holding the brush should be done by the hara, which in Japanese refers to the particular workings of the area below the belly button, which is developed over time by intense focus on the sensations of breath and gravity in the body. If the hand and arm are doing the work of holding the brush up, the resulting stroke is much less refined than if the work of holding the brush is done by the hara.

This same engagement of the hara is also emphasized in our ceramics training. In our program at the dojo, we have begun developing drills based on repetitive kneading of the clay and centering on the wheel, before quickly shaping the ceramic piece. This physical approach to calligraphy and ceramics training means that they are much more like a martial arts workout than an artistic creation.

In many of the Japanese cultural arts, there is a tradition that says it is hard to train a beginner until they have done 10,000 repetitions. And this is no less true of our style of calligraphy and ceramics. For example, in order to brush 10,000 three-character pieces from Tesshu’s training manual, you would need to brush the whole Eight Immortal poem two times per day for 100 days. You would then have a starting point for serious training.

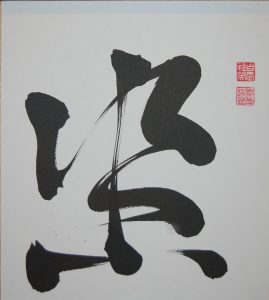

One thing that demonstrates the physicality of our training in calligraphy is that we rarely talk about the meaning of any given character or set of characters. Certainly there is a long tradition of Zen masters brushing calligraphy of a meaningful phrase. But the problem for most Western viewers of such a piece is that the translation of the phrase, the meaning of the words, immediately obscures the visceral experience of the calligraphy itself.

But the master is not trying to tell the viewer something; the master is being that something. For example, if there is a single brushed character that could be translated as “to sit,” the character itself should “sit.” There should be a sense of gravity and repose in the ink on the paper because that same sense of gravity and repose is in the person who picked up the brush.

Joining Zen Art

How can you get the most from your encounter with a work of Zen art? To the degree that you have trained seriously in Zen and learned to engage the hara, you will already begin experiencing the artwork in a physical way. And the more your sense of breath and gravity develops, the more profound the encounters become. The duality of creator and viewer begins to dissolve when the viewer joins the art.

One way to do this, even for those with limited or no Zen training, is to try to breathe your way through the strokes of ink in a work of Zen calligraphy. Pick what you think must be the starting point for a character and then use one breath to follow the path of the brush. This way you may begin to experience the art’s expression of bokki.

Related: PHOTOS: The Natural Artwork of Japan’s Buddhist Temple Walls

With a work of ceramics, if you are allowed to pick it up, don’t start by looking at the work. Instead, scan your body. Instead consider how the weight of clay in your hands is being carried in your body. If your body becomes more grounded, then you are, in a sense, coming into contact with the body of the potter. You are feeling the ceramic’s dokki.

If the ceramics are behind glass at a museum exhibit, stand squarely facing the piece. Feel how the weight of your body connects to the floor by feeling the pressure at the base of your big toes. As you let yourself feel heavier and heavier, counter the gravity by using a long exhalation to push the top of your head toward the ceiling. This kind of stance becomes a form of standing zazen (Zen meditation). Your gaze softens, and you begin to have a sense of what would happen in your body if you could pick up the bowl. With time, you may feel the glass between you and the art dissolve, and you may even feel the division between you and the creator dissolve. And all that is left is Zen art.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.