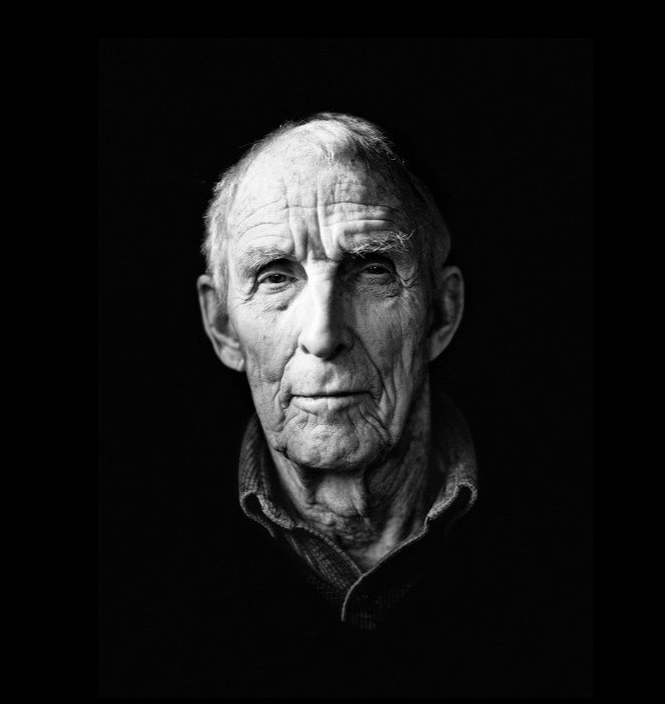

Peter Matthiessen—prolific author, naturalist, activist, and Zen priest—passed away at his home in Sagaponack, NY, on Saturday, April 5. He was 86.

His death—three days prior to the release of his newest novel, In Paradise—marks the end of his struggle with leukemia, for which he was undergoing chemotherapy.

Matthiessen was introduced to Zen practice by his late wife Deborah Love, a writer and seeker like him, at a weekend sesshin at New York Zendo in Manhattan in 1969. Love introduced him to Eido Roshi (1932–), Yasutani Roshi (1885–1973), and Soen Roshi (1907–1984); Soen Roshi would become his root teacher. He continued studies with Maezumi Roshi (1931–1995) and then Bernie Glassman (1939–), from whom Matthiessen received dharma transmission in 1989.

But Matthiessen’s life as a writer was 25 years along when he became a Zen student. His fiction, wrote Tricycle Founder Helen Tworkov in the magazine’s pages, “testifies more to the lineage of Melville than Basho.” (As Jeff Himmelman notes in a recent interview for New York Times Magazine, one of Matthiessen’s ancestors even gets a mention in Moby-Dick.)

Fresh out of Yale in 1950, Matthiessen was recruited by the CIA and sent to Paris, where he worked on his first novel. There he founded The Paris Review in order to provide a sturdier front for his nefarious activities: spying on fellow Americans suspected of communist sympathies. The literary magazine would continue to uphold what one of its editors called a “joint emploi” with the CIA’s propaganda front, the Congress for Cultural Freedom, long after Matthiessen parted with the CIA in 1953. His stint as a spy, he told New York Times Magazine, is one adventure he regrets.

Matthiessen went on to author over 30 books and won the National Book Award three times, most recently at the age of 81 for his novel Shadow Country (2008), making him the only writer to receive the award for both fiction and nonfiction. His Zen training heavily influenced a number of his works, such as Far Tortuga (1975) and The Snow Leopard (1978), but the relationship between Matthiessen’s Zen practice and writing was somewhat ambivalent. He never tried explicitly for dharma insight in his writing, and he began working on Far Tortuga, the novel most impressed, he said, by his Zen practice, before ever sitting zazen. The protagonist of his new novel, In Paradise, which takes place at a “bearing witness” meditation retreat at Auschwitz, is quick to deride what Matthiessen’s root teacher called “the stink of Zen”—self-conscious spirituality and its pretensions. “He was capable of saying ‘Zen’ with real contempt!” Matthiessen said of Soen Roshi.

Matthiessen is survived by his wife Maria Eckhart and his two sons, two daughters, two stepdaughters, and six grandchildren. In 2005, Matthiessen gave dharma transmission to Michel Engu Dobbs, baker and manager at Tate’s Bake Shop in Long Island. “When you have transmission yourself,” Matthiessen told photographer Peter Cunningham when visiting Sagaponack Zendo with Tricycle in late 2012, “you must find someone to keep the dharma alive and keep it going.” Before Engu came along, Matthiessen said, “I was really kind of resigned to childlessness.”

“I dream of simplicity, but I’m as far from it as ever,” Matthiessen told writer and Zen student Lawrence Shainberg for Tricycle back in 1993. “That is my practice, how to be in the world and remain simple. One day perhaps I’ll accept the fact that I am never going to find the simple life. Maybe the first step toward simplicity will be to accept that my life will never be simple even if I go live in a cave and subsist on green nettles like Milarepa.”

In his final in-depth interview with Times Magazine, Matthiessen reiterated that it has always been his goal to simplify himself. “I don’t want to cling,” he said. “I’ve had a pretty good run of it. . . . I have no complaints.”

—Alex Caring-Lobel, Associate Editor

More on Peter Matthiessen:

A 1993 interview with Matthiessen by writer and Zen student Lawrence Shainberg.

An extract from Matthiessen’s travel journals from Mustang, Nepal, that describes the Masked Lama Dances of the Tiji ceremony and its relationship to Buddhist teachings on impermanence.

Tricycle and photographer Peter Cunningham visited Matthiessen and his dharma son Michel Dobbs in Sagaponack in 2012 to discuss Zen transmission and lineage. Video below, article here.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.