In July 1813, a young American couple from Boston arrived in the Buddhist kingdom of Burma to preach the gospel. They came carrying religious pamphlets and bibles—as well as telescopes, globes, maps, magic lanterns, and other “world-conjuring devices” that Burmese Buddhists had never seen before.

According to religious studies scholar Alex Kaloyanides, this was the first time that Theravada Buddhism and Baptist Christianity came into contact with each other—and the encounter was transformative for both traditions. Although Burmese Buddhists largely resisted Christian evangelism, they nonetheless engaged with the material objects that the missionaries brought, reimagining both Buddhism and Christianity in the process. In her new book, Baptizing Burma: Religious Change in the Last Buddhist Kingdom, Kaloyanides examines some of these objects and what they reveal about power, conversion, and religious material culture.

Tricycle’s editor-in-chief, James Shaheen, spoke with Kaloyanides on a recent episode of Tricycle Talks to learn more about the religious landscape of 19th-century Burma, what we miss when we study religion solely through texts, and what it means for objects to hold sacred power.

You say that the material dimensions of religion can often be overlooked. What are we missing when we think about Buddhism only through written texts? The first thing we miss is the way that so many parts of society who are not literate have engaged with the Buddhist tradition. For so long, texts have been the possessions of a very small elite minority of monastics and so on. If we focus too much on canonical texts, commentaries, and scriptures, we can start to think that we are seeing a bigger picture than we really are. These texts were really the production of a very educated people with a lot of royal resources. The [turn to] material culture is a way of talking about what other people have done.

Studying material culture also reminds us that we are embodied people. Retreats, for instance, are not just about the text of a dharma talk—it’s about the whole experience of the space. So to try to understand what Buddhism was like for people in different times and places, it’s really telling to focus on some of the different sensory experiences of the tradition.

You write that the objects you found often bumped up against the familiar stories that have been told about the religious history of Burma. What surprised you about the objects you came across, and how did they resist easy or familiar narratives? The first actual physical object that I found was this Buddhist manuscript called the Kammavaca. It comes from the Pali canon, and it’s made up of excerpts for monastic rituals. It’s a beautiful lacquered manuscript, sometimes made with gold, pearl, and silver. What I began to notice about this manuscript was that not only was it carefully preserving ancient scriptures and ritual formulas, but it had all these illustrations. Some of the oldest ones had these beautiful designs of flora and fauna and interesting geometrical designs.

Later on, especially toward the end of the 19th century, the manuscript changed—not the text itself, but in the margins, these spirit creatures emerged carrying weapons and swords. These creatures become a kind of belligerent presence in these manuscripts. I realized that something was happening with these objects beyond ordination rituals—these objects were conscripted into Burmese war efforts to defend themselves against the British, and they were imbued with a certain kind of power to defend a Burmese independence. If we just look at the texts themselves and not the material qualities or artwork that happens in the margins, sometimes we miss the power they had and the reason they were produced in such a way or ended up circulating outside of the country.

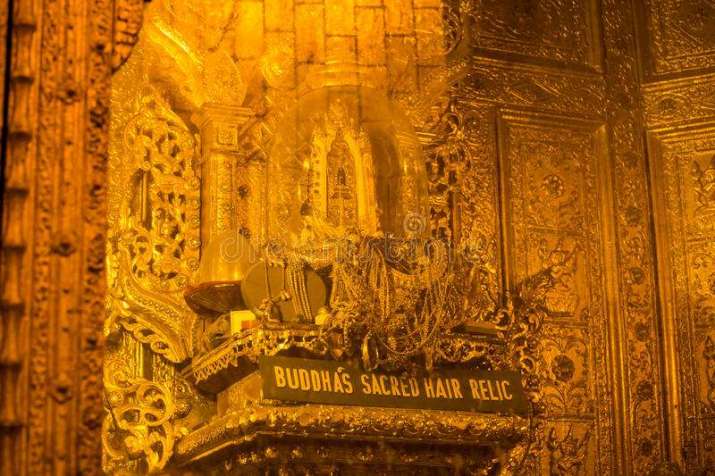

You talk about how Theravada Buddhism places special import on holy objects, as worldly materials “can mediate a relationship with a central figure who is absent from this world.” So can you walk us through the role of religious media in this tradition? Theravada Buddhism is distinctive from Mahayana in the sense that there’s an understanding that the Buddha really lived, and he really did become unbound through nirvana and no longer exists in this world. And so in the absence of the Buddha, what do followers do? We have relics and pagodas and special objects that are said to have some of the Buddha’s power, or anubhava. Objects themselves become a key place for people to experience the Buddha even after his parinirvana.

There’s no Buddha anymore here on Earth. Objects themselves become these really powerful figures that both help point people to the teachings of the Buddha, but then they themselves are also powerful in and of themselves. They can help transform the people who are devoted to them.

What does it mean for an object to contain the Buddha’s power? Is it the power to move us toward liberation? It’s been interpreted in the material that I’ve looked at both as a power to remind someone of the Buddha’s teachings, to recommit them to a certain path. But there’s also this overwhelming special power in those places, where someone can get closer to understanding the Buddha’s teachings than they would in other settings. In this presence of the Buddha’s power, one can progress toward enlightenment and have a kind of connection there that would be transformative in a way that other objects do not have the power to do.

So those places can also hold power in terms of practice: a certain momentum of practice might propel a person forward on the path. Is that right? Yes. Scholars of ritual and sacred space would also argue that there’s something about being in community and being with other people. That collective effervescence that comes together in those particular spaces doesn’t happen in other places—there’s something sacred there that is able to move people in new directions.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.