49 UP

Michael Apted, Director

First Run Features, 2006

THE UP SERIES (SEVEN UP THROUGH 42 UP)

Michael Apted and Paul Almond, Directors

First Run Features, 2004

$99.95 (DVD Boxed Set)

When I was in grade school, I was fascinated by those Disney science films that used time-lapse photography to condense the life of a plant into a minute or two. First the whitish-green shoot pokes out of the ground like a primitive alien being, driven by some blind instinct for life; then it transforms and elaborates itself, putting forth stems, buds, and leaves as it stretches its few inches or feet toward the sky, straining for air and sun; at some point its growth reaches its peak, which we never recognize until we’re just past it; then it shrinks and decays into a brown, dry husk.

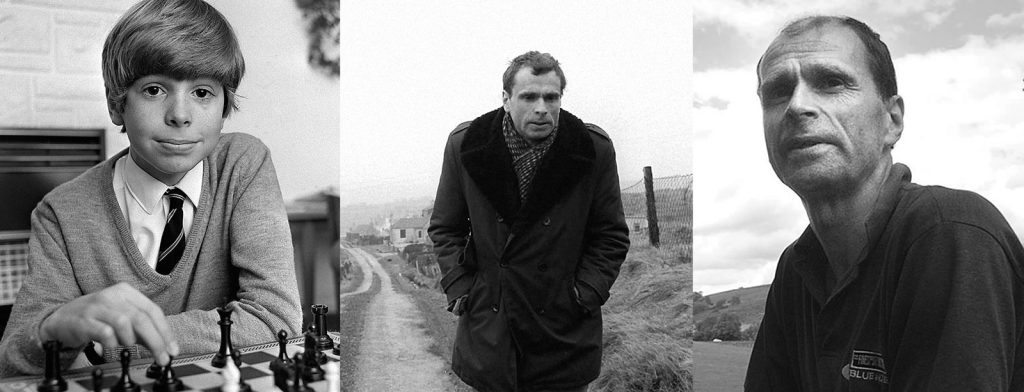

Watching 49 Up, the new film by the British documentarian Michael

Apted, is like seeing the same thing happen to people. It’s the seventh in a series for Granada Television that began in 1964 with 7 Up, which presented fourteen seven-year-old children from varying backgrounds, observing them at play and at school, questioning them about their lives, their attitudes, and their hopes for the future. After working as a researcher on the first installment, Apted returned to direct the sequels, revisiting his subjects every seven years. In this latest film, he spends almost as much time cutting back to ages 35, 14, and so forth as he does presenting 49, often shuttling back and forth with such dizzying speed that it seems almost an object study in the Buddhist formulation of birth, old age, disease, and (now starting to loom on the horizon) death. At times, in fact, the rapid cross-cutting gives us not only a sense that the stages of life whiz by quickly, but a trans-temporal point of view from which they’re all simultaneous, as in those Tibetan thangkas that, somewhere below the Buddha’s feet, show a woman as a triple image: the first a beautiful maiden, the second middle-aged, the third a shriveled crone.

The effect can be distressing and even frightening. Sweet uniformed school- girls blossom into radiant nymphets and droop into menopausal grumps. Tony, the spirited, mischief-in-his-eyes East End urchin, attains his dream of being a jockey by the age of fourteen, then realizes “I wasn’t good enough” and settles in as a cabbie by twenty-one; moments later his blonde hair fades into colorlessness and his devastating good looks dissolve into puffy middle age.

But it’s not all a forced downhill march. Our lives, of course, are a rich, subtle, often confusing mix of sukha and dukkha, relative happiness and relative sorrow: that’s why Shakespeare wrote about humans instead of house- plants. Thus Bruce, the forlorn seven-year-old shunted off to boarding school by his divorcing parents, tells the camera, “My heart’s desire is to see my daddy,” then unsurprisingly grows into a gentle but awkward, womanless, emotionally constricted math instructor. But well into middle age he’s rescued by the love of a good woman and the birth of a couple of rambunctious sons, who keep him, even in his stiff, paunchy body, cheerfully rolling about the living room carpet. Sue, after struggling for years as a single mom and office worker, finds the right man, the right job, and the right dog. The most heartening turnabout is that of Neil, who, in the earlier films, washes out of his Oxford entrance exams and becomes a homeless eccentric, wander- ing around Britain by foot with his shambling, harried gait, worrying that he’s losing his mind. By forty-nine he finally somehow pulls himself together enough to become a local councilman for the Social Democrats and a lay reader in the Anglican Church, singing sentimental hymns with touching sincerity and only a little too loud.

If these lives sounds undramatic, they are, but it’s their very ordinariness that gives the film its power, that makes it far more real than the contrived exhilarations and humiliations of TV’s “reality” shows. Yes, there are divorces and children born out of wedlock, and Tony’s wife catches him in some midlife philandering. But no one goes to jail, no one becomes famous (Nick the scientist’s great fusion- energy project fizzles), and no one comes out. Aside from Neil, no one has much of an explicit spiritual center to their lives, but mostly they’re devoted to the God of Small Things: Bruce quietly relishes coaching a boys’ cricket team on Sundays, Tony recalls driving “Kojak” in his cab, and there’s lots of digging gardens, choosing floor tiles, and playing with grandchildren who sometimes look hauntingly like their grandparents at seven.

And the beat goes on. Plodding along in their eminently conventional lives, Apted’s subjects gradually, implicitly discover that samsara is nirvana—that fulfillment lies not in some cosmic orgasm or Nobel Prize apotheosis but in the moment-by-moment of ordinary life, just as it is. At the same time we can feel frustrated that they don’t experience nirvana

in its full-blown, liberating clarity. Here are these perfectly lovely sentient beings, innocently embodying all the divinity there is (Allen Ginsberg could have had them in mind when he wrote, “Holy the lamb of the middle class”), and they’re always just one breath, one undistracted moment away from knowing it.

Visually, the passage of time is underscored by changes in film stock, from the suitably primordial feel of the black-and-white first episode to the somewhat grainy, washed-out color of the teenage installment, followed by subtler improvements up through the startlingly true-to-life quality of the seventh, as if we keep awakening from gauzy reveries of the past to the sparkling actuality of the present. And, like life itself, the series becomes more self-referential as it goes on. (There’s a tribe in South America who speak of the past as being before them because they can see it, and of the future as behind them because it’s yet unseen.) Increasingly, the subjects muse or joke about their own responses in earlier interviews, reflect upon the difficulty of having their inner lives repeatedly sliced open for the entertainment of strangers, grouse about being misrepresented, and threaten to drop out. Apted himself is a perfect foil for these complaints, invisibly manifesting as a BBC bass-baritone voice-of-God, posing often impertinent questions from just outside the frame.

The film moved me and my friends to play a sort of parlor game, where we imagined ourselves as characters in it and each described what our every- seventh-year installments would look like. It’s an instructive and sometimes unsettling exercise (highly recommended) that in turn reminded me of something else. At one point in my Buddhist career I studied with Ngak’chang Rinpoche, a colorful lama from Wales who described himself as “a harmless English eccentric” and who specialized in subverting people’s cozy psychological complacency, or, as he put it, “setting their underwear on fire.” He sometimes led workshops where everyone had to bring in snapshots of themselves at different stages of their lives: as a toddler in the sandbox, as a student with their college sweetheart, and so on. They’d set out these photos and try to feel the person they were when each was taken, what mattered to them, their worldview, their hopes and fears. Gradually Rinpoche led them to look for the person, the self, that allegedly runs like a thread through all those beads. The more they looked, the more the notion of an absolute, continuous, solid, permanent, definable self fell apart, giving way to anatta, no-self, which is the essential nature of our intrinsic freedom.

A number of times, Apted asks the forty-nine-year-olds if they can identify with the seven-year-olds who go by their names in the first film; they unanimously reply that they can’t find themselves in those children. Correct. Not there, not here. All is process, all is flux, an ever-simmering molecule chowder, little eddies of which now and then bravely proclaim themselves as selves (reassuringly backed up, as we often see in this film, by family photos on the mantel), only to dissolve into the chowder once again. In time we convince ourselves we’re selves, then dig in and resist as time deconstructs our conviction. If we can let go of that futile resistance, we can be free.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.