Ten New Songs

Ten New Songs

Leonard Cohen

Sony Records: 2001

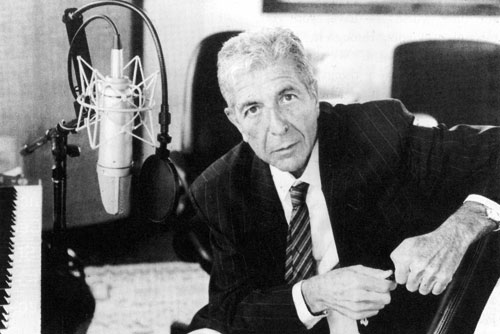

Leonard Cohen’s songs, a friend said recently, offer “music to die by,” and as soon as I heard that, I realized one source of their Buddhist radiance. Death, loss, and renunciation toll through every stanza of the benign hymns of passage on his latest album,Ten New Songs, and yet they’re accepted, even embraced, as warmly as the love and life that have preceded them. When a poet of sixty-seven releases a new set of songs, it’s a safe bet that they won’t be about the classic pop themes of “Love, love me do,” or “Baby, we were born to run,” and indeed these new songs are all about the need for letting go. Cohen sings with the sober wisdom of one who’s been living with death for quite a while now.

When the record begins—as is more and more the case as Cohen gets on one’s first response is, likely, shock. His voice sounds as if it’s emerging from the far side of the grave: a distance, muffled growl, as of a door slowly opening (or, in this case, more likely, a door creaking shut). The sound is spare, to the point of minimalism; the beat, even more than in early Cohen, is funereal. His croaks issue forth over a basic, leaden drone that sounds as if it were recorded (as it was) in a friend’s backyard late at night; much of the time, the singer’s bass profundities are almost drowned Out by the sweeter sounds of his colleague Sharon Robinson (her husband, Bob Metzger, is the only musician on the record, playing a faraway guitar). Whatever rock ‘n’ roll was intended to convey, I think, it was never meant to carry a sound as worn and old and rough as this.

Yet as you begin to settle into the very particular mood that develops—that of a cabin high up on a chill mountaintop in the dark, a single light on inside—you see that it is in the raggedness that the radiance can be found. There is a crack in everything, as Cohen (following Emerson) sings on a recent album, and that’s how the light gets in. The opening song here, “My Secret Life,” tells us, in effect, what to expect—for the secret life this singer confesses to is not one of venality and deceit and ambition, but the opposite. His secret, at this point in his life, is not that he’s fallen, but that he occasionally manages to rise above it all. The mystic’s way in every tradition is to invert the world by remaking the very terms with which it presents itself (turning its words upside down as a way to rum its values inside Out); Cohen’s secret life (since he’s as impatient with the dogmas of the monastery as with those of the world) is the place where he makes love in his mind and refuses to see things in black and white.

As the songs go on, you see that, at some level, that’s what they’re all about. Babylon and Bethlehem-his favorite themes, his favorite places—but seen in a new light, because Babylon looks different once you’ve been to Bethlehem. Cohen first met Joshu Sasaki Roshi roughly thirty years ago, and since then they’ve been drinking buddies, friends, and in their maverick way, student and teacher. For much of the nineties Cohen actually went to live near Sasaki at his Rinzai Zen monastery in the high, dark, spartan hills behind Los Angeles, cleaning up, doing odd jobs, and cooking for the Zen master. He says (almost with pride) that he’s come down from the mountaintop now—”I am what I am,” announces one song, and another speaks of how certain “gifts” can’t be exchanged (his gift, one assumes, being for worldliness)—and yet one feels that he would only leave the monastery once he was sure that the monastery would not entirely leave him. For much of the record it feels as if Mount Baldy Zen Center itself—or the meditation hall—is growling over the music.

The result is that we, too, have to let go, of all Out easy assumptions and pieties. The second song, “A Thousand Kisses Deep,” tells us again how the whole parade of human endeavor looks different if you see it in the light of death (or eternity: the terms hardly matter). We claim a small victory here and there, we think we’ve taken a step forward, and yet it all means very little in the face of Out “invincible defeat.” And yet, even as we move towards oblivion, we go back to “Boogie Street” (or samsara, as it’s usually called), and when we fall, we “slip into the Masterpiece.” You can’t renounce a desire until you’ve lived fully through it, and Cohen, who sometimes has the air of having entertained as many desires as a whole community of monks, has always been a believer in embracing everything fallen, the better to let go of it. As the opening line of the next song announces, “I fought against the bottle / But I had to do it drunk.”

Cohen has long been one of the great realists among the romantics, never afraid to look at truth, however much it hurts. Indeed, part of his strength comes from the fact that he’s always written so openly about his losing battles with women and intoxicants and the less exalted parts of himself. Here he brings that same merciless clarity to the very platitudes of the pop song. “I know that I’m forgiven,” he sings later in the third song, “But I don’t know how I know / I don’t trust my inner feelings— / Inner feelings come and go.” The next one opines, beatifically, “May everyone live,” and then goes on to add, “And may everyone die. Hello, my love, / And my love, Goodbye.” In a sense, these are anti-pop songs, not least because they nearly all seem to end in emptiness, the void. And yet it is a nothingness that the singer manages to accept with calm.

Cohen has long been one of the great realists among the romantics, never afraid to look at truth, however much it hurts. Indeed, part of his strength comes from the fact that he’s always written so openly about his losing battles with women and intoxicants and the less exalted parts of himself. Here he brings that same merciless clarity to the very platitudes of the pop song. “I know that I’m forgiven,” he sings later in the third song, “But I don’t know how I know / I don’t trust my inner feelings— / Inner feelings come and go.” The next one opines, beatifically, “May everyone live,” and then goes on to add, “And may everyone die. Hello, my love, / And my love, Goodbye.” In a sense, these are anti-pop songs, not least because they nearly all seem to end in emptiness, the void. And yet it is a nothingness that the singer manages to accept with calm.

The sound, as always, is sepulchral, and Cohen has always had an after-midnight quality to him (one reason why the reality of suffering pulses through them); and yet in the earlier songs, one felt that he was delivering his ragged, intimate confessions to someone else (a young woman, most likely, with a bottle nearby). Here it feels as if he is thoroughly alone, talking only to the dark. Lovers of the renegade adventurer will still find him kneeling at the feet of women, and talking of “getting fixed,” and yet there’s less of a sense here that these pleasures will lead to anything, or solve anything. Writing of death, he presents us with the least unsettled (the most composed) songs you could imagine; there’s scarcely a trace of wistfulness or self-pity on the whole recording.

“The light came through the window,” one song begins, and the singer, in his cabin on the mountain, no doubt (where these songs were written), writes about the motes of dust that are suddenly visible in the sunlight. Nothing could be more ephemeral, and yet—this is the heart of the whole record—nothing could be more beautiful. The world is an illusion, and yet it’s the only world we have; you get through it by going through it, “living your life as if it’s real.” We throw our arms around the very things that flee from us. It’s all the more moving coming from a writer who’s written some of his most haunting songs over the decades about how beauty (and not its loss) can bring redemption.

Cohen was one of the leading poets in Canada before he ever recorded a song, of course, and he’s long fit squarely into the classic devotional tradition (on his last album, Field Commander Cohen, among thanks to family and friends, he acknowledges his gratitude to Jelaluddin Rumi). When he writes a country and western ballad called “Coming Back to You,” all its power and resonance come from the face that you can’t tell whether that’s a “you” or a “You” (and, best of all, it doesn’t really matter). Here, sitting in the dark alone-you can feel the confinements of time and space—he sings his most personal songs in honor of the impersonal; you hear traces of John Donne, say, or George Herbert, but often the small, dark verses of power and compression sound most like Emily Dickinson—if she’d had a lifetime full of lovers to remember in her lonely room.

Part of the particular attraction of Zen for Cohen, one feels, is the fact that it offers a world outside all categories. No right, no wrong; no black and white. No life, no death, no nirvana or samsara. And one important aspect of this freedom is that there is no sense in which he has to conform to any standard dogma about what he should or shouldn’t be doing. In his 1984 collection of psalms, Book of Merry, he wrote a paragraph-Iong description of his teacher that is as clear and wiry a description of the Zen experience as any that I’ve read, and that ends (a classic Zen surprise) with “When he was certain that I was incapable of self-reform, he flung me across the fence of the Torah.” It’s no surprise, then, that many of the songs here sound like they come out of the Bible, with their talk of Babylon (and even of the Cross).

Yet, for all the open-endedness, Ten New Songs seems to me as unflinching and deep a record of the Buddhist experience as any I can remember encountering. Renunciation, after all, is only as strong as one’s longing for what one is giving up (and one is never in doubt about the power of Cohen’s desire); our sense of another order of things is only as meaningful as our understanding of the world around us. In his earlier songs, Cohen often almost shouted out his anger and restlessness in imagery of war that told us, over and over, that the world is a rough place, and violence is often called for; here, there is a new tenderness that suggests that the beauty of the world lies partly in the fact that it doesn’t last. One song explicitly sings about the dance between the “Nameless and the Name” (not what you usually encounter on the Billboard Top 40). Another talks about a couple “radiant beyond your widest measure.”

That last line comes from the song “Alexandra Leaving,” and of all the beautiful songs on the record, this is the one I can’t get out of my head. Many of us, when young, read the poems of C. P. Cavafy, the great poet of exile, about his sense of sadness and loss when leaving Alexandria; here, a poet of a higher exile writes about his sense of gratitude and honor even as one Alexandra leaves him. In his younger days, Cohen almost defined himself as the man who left women in order to pursue his quest (the two most melodious songs on his first record were “So Long, Marianne” and “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye”); now it is he who is left watching as love and life pass away.

As he watches Alexandra leave, he’s tempted to find ways to cage the experience—to control his heart-by turning to his mind. He can say he just imagined the whole thing. He can tell himself he knew it was coming all along. He can say it was bound to happen. But over and over, he tells himself (referring to himself, typically, as “you”) not to hide behind such strategies, or choose the “coward’s” way of talking of “the cause and the effect.” He has to take his loss as a man; more than that, he has to take it all as the greatest bounty he’s likely to find. “Go firmly to the window,” he tells himself, and “drink it in.”

I listen to these songs in the dark autumn nights here in Japan, and I feel as if I’m being taken as close to the unsayable as words can really take us. There’s nothing passing in these songs (their language utterly transparent, their words so simple that they suggest many other words behind them), and yet things passing is their only theme. They give you nothing to hold on to-no specifics about time and place—and yet they go right to the heart. They’re comfortable with mystery, you could say. Then the sun rises again outside my window, and I see the brilliance of the autumn skies, even as the leaves turn and fall, and the chill and dark of winter draws a little closer-and I feel 1’m hearing the songs being sung in a different key. Hello, my love, and my love, Goodbye. ▼

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.