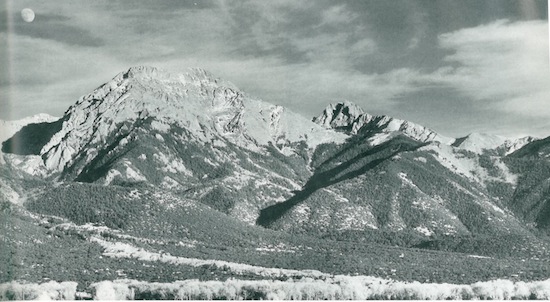

On a glorious July morning in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, a crowd made its way through crystalline air along a dirt road festooned with prayer flags towards the Tashi Gomang Stupa. Carmelite monks walked alongside devotees of a local ashram, Buddhist practitioners of various lineages among local farmers and ranchers, New Agers and the merely curious. For weeks Tibetan lamas had been gathering to prepare for this day, the birthday of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, when the forty-one-foot-high stupa would be consecrated. Above the stupa and to the east rose the fourteen thousand-foot-high snow peaks of the Sangres, to the west the view stretched forty miles across the San Luis Valley to the San Juan mountain range. To the south, towering over the Great Sand Dunes National Monument, rose Mount Blanca, known as Sis-na-jin to the Navajo and to the Hopi, the Sacred Mountain of the East. Visiting Tibetans remarked on how much the scenery reminded them of their own homeland.

The Tashi Gomang Stupa was built for His Holiness the Sixteenth Gyalwa Karmapa, head of the Kagyu lineage of Tibetan Buddhism. In 1980, a year before his passing, the Karmapa visited the Baca Grande Estate where the stupa now stands, marking the beginning of a small but flourishing Buddhist presence in this stunning remote location in southern Colorado. In addition to the Karmapa’s lineage, current dharma centers include the Crestone Mountain Zen Center, under the direction of Richard Baker Roshi, and three centers of the Tibetan Nyingma lineage directed by Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche, Gangteng Rinpoche, and Kusum Lingpa Rinpoche. Many individual practitioners have made the Baca their home for long-term retreats. As one visiting Tibetan rinpoche remarked, upon inquiring about the availability of suitable caves, “this is an excellent place to achieve enlightenment.”

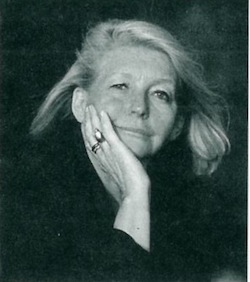

The two-hundred-square-mile Baca Grande Estate had its origins as a land grant made to the Baca family by King Ferdinand of Spain in the nineteenth century. After that, the estate passed through various hands until it was acquired by the Arizona Land and Cattle Corporation, which developed as a retirement community in the 1970s. This venture proved unsuccessful, and in 1978 the financially troubled corporation was acquired by Maurice and Hanne Strong and several partners. Maurice Strong, the Canadian Undersecretary General of the United Nations who organized the Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit of 1992, had long promoted environmental causes. Hanne, his Danish wife, felt a deep connection with both Buddhist and Native American traditions. Together, they had taken lay precepts with the Karmapa at Rumtek monastery in Sikkim.

“For thousands of years the indigenous peoples of this continent have considered this place to be one of the great spiritual centers of the world and a place of great healing,” says Hanne Strong, who felt an immediate affinity with the Baca Grande. “They have come here for some of their most sacred ceremonies, and their holy people, shamans, came here to seek their powers and develop enlightened states of mind.” According to White Rainbow, a Cree medicine man from Alberta, “In this sacred land there are keepers, grandfathers and grandmothers, who have been here for thousands of years. Our people would come here to rest, to get clear vision and guidance. This land is sacred; there is a great purpose for this place.”

The Strongs foresaw a different kind of development in the Baca. Land was set aside for a number of spiritual, Native American, and environmental groups. Aside from that of the Karmapa, these included a Carmelite hermitage, the Haidakhan Universal Ashram, the Sri Aurobindo Learning Center, Lindisfarne, and the Baca Center for High Altitude and Sustainable Agriculture. In turn, this new development attracted a variety of artists, craftspeople, naturalists, healers, and New Age seekers of all kinds to the Baca Grande and the adjoining village of Crestone.

At times it seemed that attendance at a Lakota sweatlodge or a Tibetan empowerment was de rigueur for acceptance in certain social circles in the Baca. At other times, this new community appeared to have all the trappings of a full-fledged New Age circus—a situation that did not sit well with the already established retirement community, many of whom had military backgrounds. Shirley MacLaine acquired land and was rumored to be planning a two-hundred unit “psychic workout” center.

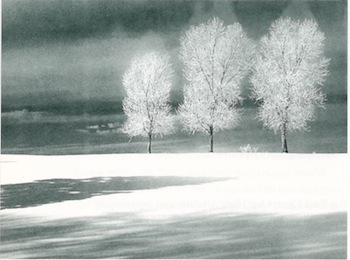

Inevitably, conflicts arose, and building remained slow. By 1988, there were still only 136 homes in the Baca. The combined obstacles of a nonexistent economy, harsh winter climate, extreme remoteness, and lack of entertainment, as well as the possibility of something less than harmonious relationships with one’s neighbors, discouraged the merely frivolous. But a core of dedicated spiritual practitioners, environmentalists, and artists who had fallen under the spell of the Baca’s awe-inspiring beauty remained, determined to stick it out.

And so Buddhism in the Baca Grande began to take root. The Strongs had hosted numerous Tibetan teachers, including His Holiness Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche and Urgyen Tulku. A small stupa had been built and Tibetan lamas had become a familiar part of the landscape, but no actual centers had yet been formed. Then in 1988, a small group assembled to realize the Karmapa’s vision for the Baca Grande. This included a Tibetan medical center, a monastery, a retreat center and an entire lay community. A house was acquired for a meditation center, and the group was asked to build the Tashi Gomang Stupa to consecrate His Holiness’ land. Around the same time, William Irwin Thompson, the founder of Lindisfarne, turned his facility over to Zen master Richard Baker Roshi, and the Crestone Mountain Zen Center was established.

Khenpo Karthar Rinpoche, the Karmapa’s representative in the United States, came to select the “eye of the land,” the most suitable place for stupa construction and blessed the site. Offerings were made to local deities and spirits and permission was asked of the Earth Devi—actions that seemed particularly appropriate in the Baca Grande—and work on the stupa slowly began.

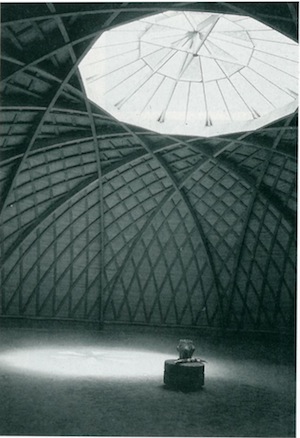

Meanwhile, Richard Baker Roshi was establishing the Crestone Mountain Zen Center. Baker, dharma heir of Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, had been looking for a principal practice location for Dharma Sangha, the organization he founded after leaving San Francisco Zen Center in 1983. The combination of an offer of the Lindisfarne facility and the lure of the pristine surroundings proved irresistible. Baker’s activity in the Baca has flourished. A magnificent new zendo was recently completed, and practioners sit zafu to zafu in a newly finished hotoan, or dharma retreat hut.

Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche, founder of Samten Ling, a Nyingma retreat center now being established in the Baca Grande, has a retreat cabin perched several hundred feet up a steep hillside overlooking a glorious mountain meadow. Kongtrul Rinpoche, now thirty-two years old, was a close disciple of His Holiness Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche. He met his American wife, Elizabeth, in Nepal, and in 1989 they moved to Boulder, where he was invited to join the faculty of Naropa Institute.

“I was looking for retreat land and came to look at some that had been offered to His Holiness Khyentse Rinpoche. I was very impressed by the sense of drala and windhorse—Tibetan terms which he defines as “a powerful sense of nature, wakefulness and protectiveness at the same time.” After corresponding with Rabjam Rinpoche, Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche’s grandson and dharma heir, it was agreed that Kongtrul Rinpoche would do something with the land himself.

He resigned his post at Naropa and began designing a community very much along the lines of a traditional Tibetan retreat center, a place where he could go on retreat himself, while guiding his students to do the same. “I want the students to have a path where they can do nine or ten years of retreat training until they become independent and then they can do what they like.”

The Manitou Foundation, set up by Hanne and Maurice Strong, has also given land to two other major Nyingma teachers, Gangteng Rinpoche and Orygen Kusum Lingpa Rinpoche. Gangteng Rinpoche was born in 1955 and has his main seat at Gangteng Gompa in the Black Mountains of Bhutan. During an overnight visit to the Baca Grande en route from Santa Fe to Boulder in 1994, seeing the Tashi Gomang Stupa under construction, he hurled a large piece of turquoise up into the interior and declared that this would be the place for his North American center.

Orgyen Kusum Lingpa Rinpoche still lives in the remote Golok region of eastern Tibet where he is highly regarded as a terton (a discoverer of hidden teachings). He was imprisoned for twenth-three years by the Chinese communists and his hands bear witness to the torture he endured. Upon visiting the Baca Grande, he too decided to make it his main center for practice in North America. He has also performed ceremonies with visiting Hopi elders to pray for the well-being of the earth.

Addressing the seven hundred people who gathered to witness the consecration of Tashi Gomang Stupa on July 6, Bokar Rinpoche said, “This gathering is something miraculous. It has come about not from any kind of obligation, but from our potential and fundamental goodness—an expression of warmth. To embrace with a loving heart goes beyond nationalities, beyond the notion of religion altogether. Part of the feeling of the fundamental human dignity is that we are, as human beings, endowed with being honest and loving and caring for each other. A loving expression of our commonalities, that is the experience of this celebration.” Hopefully the same spirit will remain true as Buddhism in the Baca Grande makes its way into the future.

Mark Elliott is a documentary filmmaker who lives in the Baca Grande. His latest videotape is The Bloodless Valley, about the Baca Grande. He is currently completing another on the creation of the Tashi Gomang Stupa.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.