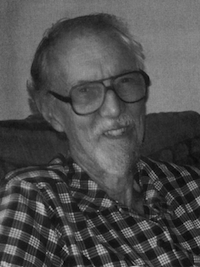

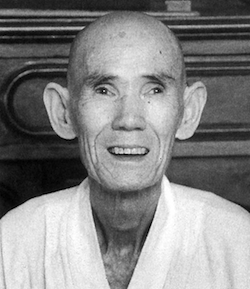

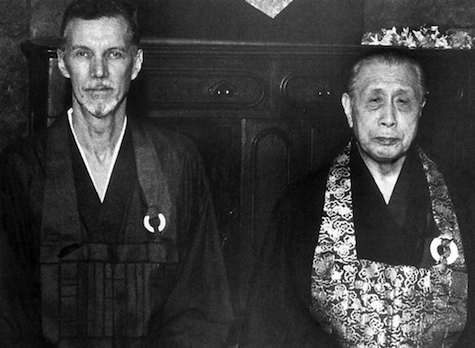

Robert Aitken, the dean of American Zen, received permission to teach in 1974 and dharma transmission in 1985, both from Yamada Roshi. During World War II he was held by the Japanese as a civilian internee captured on Guam and during his imprisonment was exposed, by chance, to the book, Zen in English Literature, by R. H. Blyth. Later, the two met during internment in the same camp. Aitken Roshi demonstrated against nuclear testing in the fifties, for unilateral disarmament in the sixties, and against the Trident submarines in the late seventies; he counseled draftees during the Vietnam War and cofounded the Buddhist Peace Fellowship in 1978. He has called himself a feminist, performed ceremonies for aborted babies, and advocated sexual equality within a Buddhist community where historically none has existed. The author of nine books on Zen Buddhism, including Taking the Path of Zen and Original Dwelling Place, Aitken Roshi founded the Diamond Sangha in 1959 with his late wife, Anne Hopkins Aitken. Today he lives in retirement in the district of Puna on the Big Island of Hawai’i in a house close to his son. He is presently at work on a commentary on The Blue Cliff Record, a collection of koans compiled in twelfth-century China.

Fifty years ago, yours was a somewhat lone voice in the attempt to integrate Zen Buddhism with an American sense of social justice. Now you have a lot of company, and the movement of “engaged Buddhism” is described as a new paradigm. Is it?

Yes. Because traditionally Buddhism was confined to the monastery, where the vow to save the many beings was very abstract on the one hand, and quite confined on the other. In the early years of this century some Buddhist monks, influenced by Western thinking, joined in the Tokyo streetcar strike. And their bishops were admonished that they could lose their status if this kind of radical action continued. From the beginning, it has behooved the Buddhist establishment in Japan to toe the political line. Now, the Myohoji sect of Nichiren Buddhism exploded this pattern after the war, under the influence of their teacher, Nichidatsu Fujii, who had studied with Gandhi. Today the Myohoji monks chant at trouble spots all over the world. In Sri Lanka two Myohoji monks were assassinated as they walked along chanting. The Myohoji monks have put themselves on the line as active peacemakers. They have a very simple kind of metaphysics—you recite the name of the title of the Lotus Sutra, and that’s going to convert the world: “Namu Myoho Renge Kyo.”

Do you think that will convert the world?

There are all kinds of people in the world. I’m not going to judge the quality of transformation people experience. In 1976 I took part in the Continental Walk, led by four Myohoji monks. And walking in the thin air of the high plains of the Texas Panhandle, from the New Mexico border on into Amarillo and up to Oklahoma City, my salient memory is chanting “Namu Myoho Renge Kyo” in that clear upper air, so beautiful and so penetrating. There’s no doubt that it had an effect. The leader was an older man with a fearful burn scar on his shoulder. In his monastery, all the monks had burned themselves in solidarity with their brother monks in Vietnam who had immolated themselves. Each took a bundle of incense and tied it to their arms, lit the bundle, and sat while the incense burned down. And their abbot placed such a bundle on each arm and each leg. Some people rather smile at this simplistic way of Myohoji Nichiren Buddhism, but I find this expression of solidarity with suffering very impressive.

What makes engaged Buddhism Buddhist?

It has classic roots. Lately I’ve been studying the Fa-yen school, which was the last school of Ch’an to develop. In case seven of The Blue Cliff Record, a monk comes to Fa-yen and says:

“I am Hui-ch’ao. I ask the teacher, ‘What is Buddha?'”

So Fa-yen says, “You are Hui-ch’ao.”

There are all kinds of pitfalls in this response—be careful! Fa-yen’s evocative words are like a blow in the night. What happens to Hui-ch’ao? What happens to us? This is not a matter of logic. It’s the bamboo telegraph across space and time.

Now, Fa-yen’s teacher was Ti-ts’ang. A monk named Hsiu comes to Ti-ts’ang and Ti-ts’ang says:

“Where have you been?”

And Hsiu says, “The South.”

And Ti-ts’ang asks: “How is Buddhism in the South?”

And Hsiu answers, “It is widely discussed.”

So Ti-ts’ang says, “How can this compare with planting my fields and harvesting rice?”

Hsiu says, “How about the Three Worlds?”

Ti-ts’ang says, “What do you call the Three Worlds?”

Now, the Three Worlds are past, present, future; they are the worlds of desire, form, and no-form; they are the worlds of the born, the unborn, and the dead—there are a lot of different categories, you see! Which Three Worlds are you talking about? In other words, Ti-tsang says, “Come off it!” And when all those concepts are gone, really gone, you have nothing. What happens then?

Would it be “planting my fields and sowing my rice?” Is that attending to the Three Realms?

Not necessarily. What Ti-ts’ang and Fa-yen, and all these Ch’an teachers are trying to do is enable us to see into particular contours of our nature and the nature of the world. Ultimately it is a matter of turning over in bed and finding there is nothing. That is one kind of experience: Turn over in bed and see nothing at all. It is personalizing the dharmakaya—if we may indulge in some concepts here. The Three Bodies of the Buddha are the dharmakaya, thesambhogakaya, and the nirmanakaya. These three are exactly the same, identical. They are a three-part complimentarity. But we tease them apart just to see their aspects. The sambhogakaya is what Thich Nhat Hanh calls “interbeing.” A very happy coinage. The sambhogakaya is called the “Body of Bliss.” Why? Because the boundaries are gone. The skin is seen for what it is—completely porous. Everybody flowing in and out. We’re all in it together, so with that genuine experience of turning over in bed and seeing nothing—that genuine experience of “I don’t know” to the very bottom, that genuine experience of complete equanimity—there is also the experience, at the same time, that we’re in it together. And the third point, the nirmanakaya, is the unique Buddha. The precious Buddha. There’s no one with your face, and there will never be anyone again. And this is true for everyone and everything, every leaf on every tree. So we have emptiness, interbeing, and uniqueness, each of them fundamentally important, each of them standing alone, so to speak; and yet without one the other two will collapse. So by destroying this notion of finding essence by discussion, destroying this notion of the Three Worlds, destroying this notion of Buddha, you see, we can penetrate that hard layer of conceptual thinking, get right through to the very bottom, from which all concepts arise.

Traditionally in Buddhism—and Zen in particular—compassionate activity arising from the nonconceptual experience of reality was primed by monastic commitments. Is what we’re calling the “engaged” expression of Buddhism new because Western Buddhism is evolving outside the monastery?

We are suddenly looking at our vows in new ways because the monastery walls are down. They’re clearly down for us in the West, and so we’re trying to feel our way. How is it appropriate for us to carry out our vows when there are no limits?

Has the form of that vow—its expression, including the monastic prototype—been shaped by political history all along?

Absolutely. Of course, political history has been shaped in turn by cultural attitudes.

Has the Zen ideal, in which meditation embodies the ultimate expression of wisdom and compassion, always been informed by political circumstances, going all the way back to Bodhidharma facing the wall?

Maybe Bodhidharma’s first idea was to talk to the emperor in hopes that he would convert the country. If so, it didn’t work. See, the emperor was known as the Buddha Emperor, because he sponsored all these great conferences on Buddhism, and he would don Buddhist robes and give dharma talks and scrub the temple floors. He was a very sincere Buddhist. But he didn’t get it. He says to Bodhidharma, “What is the first principle of the holy teaching?”

And Bodhidharma says, “Vast emptiness, nothing holy.”

So the Emperor asks, “Then who is this standing here before me?”

And Bodhidharma says, “I don’t know.”

That’s where it all started, with a political idea. When it didn’t work out, then the limits were set. Suppose in those circumstances, I roll over in bed and see nothing. What happens to me? I am energized, realizing the other is no other than myself. Also, I am altogether unique, and you are altogether unique. So how does this play out in old China and Japan? It plays out to the perimeter of the monastery walls. That’s as far as it goes. Or the teacher gets directly involved in politics. Or maybe does some counseling for parishioners—that sort of thing. That’s all they could do. But now there are no walls, and we’re feeling our way.

When we speak of engaged Buddhism, are we talking about something called Buddhist social action, or are we talking about Buddhists who are social activists?

There’s an element of both. With Liberation Theology, small cells of twelve to eighteen people gather weekly for Bible study with the intent to learn how Jesus is devoting himself to the poor and to the downtrodden and to the betrayed. And by this study, the folks are empowered, feeling that Jesus is with them. Now, if we study the sutras and the teachings and if we practice in our own way as Buddhists, we too are empowered, for we realize not that Jesus is with us or that Buddha is with us but rather that we all share the same nature; in fact, the other is no other than myself. If we realize this to the very bottom, then we can’t bear to experience the suffering of others without trying to help. We are empowered in that way.

You seem to be suggesting that without going forth from the monastery into the world, our understanding remains dry, or desiccated, or without heart.

Well, we can point the finger in that way, but we are pointing from our own position of religious power in our own place, in our own environment of relative tolerance of other religions. The monasteries—in East Asia, at least—were there on sufferance. They were permitted to be there, so long as they behaved. The situation in Southeast Asia is very different: Buddhism is part and parcel of the culture. In Japan it has never been anything more than an influence.

What is essential to Zen? What is it without which Zen would not be Zen?

Zazen.

Would you accept zazen as a form of social action?

Probably not generally, but it could be.

Is there any place for Zen monasticism as we knew it in Japan?

No, there is not. I don’t think so. What good is it, anyway?

The monastery?

Yeah. It doesn’t fit our culture. It’s time to move out. Certainly, as religion evolves, certain things are lost or dropped and certain things are gained. I do not want to convey the Japanese Buddhism that I learned. What I am seeking to do, as best I can, is to convey what realization is for us in the Americas and in Europe and in Australasia, without losing the fundamental points. When Yun-men said, “Every day is a good day,” he was saying something that completely transcends Zen. Completely transcends anything cultural. And if you really see into what Yun-men is saying, nothing is lost. A certain cultural accretion or cultural clothing is dropped off because when I say that to you now, I’m not standing on a podium with my monks standing before me, with the expectation that someone will come forward and make three bows and challenge me.

Yet the monastery has been the container of the Zen lineage. When we shatter the container, how do we continue to transmit the lineage?

We still need a container, that’s for sure. In one sense, it is the Zen center. It is also the lineage itself. The container is one’s responsibility to a lineage. I must not betray my old teachers, you know. I must not water down the dharma. I must not establish an agenda whereby I am simply using those old teachers to forward my own views. But rather, let me try to convey those profound insights.

Robert Aitken, the dean of American Zen, received permission to teach in 1974 and dharma transmission in 1985, both from Yamada Roshi. During World War II he was held by the Japanese as a civilian internee captured on Guam and during his imprisonment was exposed, by chance, to the book, Zen in English Literature, by R. H. Blyth. Later, the two met during internment in the same camp. Aitken Roshi demonstrated against nuclear testing in the fifties, for unilateral disarmament in the sixties, and against the Trident submarines in the late seventies; he counseled draftees during the Vietnam War and cofounded the Buddhist Peace Fellowship in 1978. He has called himself a feminist, performed ceremonies for aborted babies, and advocated sexual equality within a Buddhist community where historically none has existed. The author of nine books on Zen Buddhism, including Taking the Path of Zen and Original Dwelling Place, Aitken Roshi founded the Diamond Sangha in 1959 with his late wife, Anne Hopkins Aitken. Today he lives in retirement in the district of Puna on the Big Island of Hawai’i in a house close to his son. He is presently at work on a commentary on The Blue Cliff Record, a collection of koans compiled in twelfth-century China.

Social action—as distinct from radical political action—is sanctioned—even, shall we say, favored—by the Protestant ethic that continues to dominate this culture. Is it necessary to make a special effort to delineate Buddhism and social action so that we don’t just end up with Protestant Buddhism? Or perhaps I should ask, is it possible to have anything but Protestant Buddhism?

Inevitably, eventually, there’s going to be a synthesis. And Jeffersonian democracy is going to play an important role in whatever emerges as North American Buddhism. When you read Chuang-tsu, for example, or Mencius, or even Confucius, you realize that Zen has roots in those Far Eastern philosophies. Mencius speaks of the outer world as the inner world almost a thousand years before Bodhidharma appeared in China. So Dhyana Buddhism and Confucianism and Taoism came together as parents of Ch’an and there is really no missing link, no place in that line between Bodhidharma and Ma-tsu and Shih-t’ou eight generations later, where we can say it took place. Suddenly with Ma-tsu and Shih-t’ou you find full-blown Ch’an. Suddenly Ch’an appeared in the world, its own thing.

Roshi, your first teacher, Senzaki Sensei, called himself a “marginal” monk. And over the years, you have described yourself as “marginal.” It’s a word that appears in your language frequently and in a compelling way. And I’m wondering, with so much effort being made now to merge Buddhism with our cultural values, where will the marginal view arise from? Or how can it be maintained and cultivated for the benefit of society? I’m thinking of [Thomas] Merton’s views here.

Well, Senzaki not only considered himself to be a marginal person, but he considered that Zen Buddhism would always be marginal. Someone asked him if he could visualize Zen becoming a mass movement, and he said no. He said nuclear physics is not for everybody. Now he was not speaking arrogantly there, but rather he was seeking to say that there’s only a certain kind of person who can go into nuclear physics and only a certain kind of person can go into Zen. We spoke earlier about the differences between people and how there are the Myohoji folks, who find personal transformation in just reciting a certain mantra and dressing a certain way, and so it is possible that a person can consider himself or herself a Buddhist without ever practicing formally. And that’s fine. But as to actually merging the deepest possible understanding in Zen practice with the humanistic and altruistic views of this country—well, the Zen point of view can inform some of the things that others are doing. Conversely, certain poets like Wallace Stevens inform my practice. Many things inform my practice. But I can’t say that there is a merging yet. It’s early days. Something new will appear—I don’t know what yet—like Ch’an came forth new, like a baby comes forth new.

What inspires you most now?

If I can cultivate one or two truly realized successors, I’ve done my job. Soen Roshi used to say, “It’s the job of the Zen master to find a successor with two open eyes. If he can’t do that, at least with one open eye. If he can’t do that, at least maybe one eye can be half open.” That’s my fundamental task, and I have no idea how it’s all going to play out.

And where would the main thrust of social action lie now? What is the most pressing concern?

Certainly ecology is the first thing that comes to my mind—realizing that we’re all in it together. We’re interdependent, and we arise together and we depend upon each other. In Zen terms, we are actually not only participating with each other but within each other. This is the ecology under which all the other concerns are subsumed—things like peace and conflict resolution, civil rights, women’s rights, gay rights.

This is your primary concern?

I know that somehow I’ve gotten a reputation for being particularly concerned with social action, but really my primary concern is to help people and encourage people to find their own essential selves. And the essential self of the universe. All things arise from that. On that path, of course, we can be socially concerned. We don’t need to wait until we are enlightened before we start moving out. But it’s very important to be on that path. And my role is to help people on that path. That’s my fundamental role. I don’t think that I have kept a particular goal in mind. Nor have I aspired to leave a certain legacy. I have simply, well, “followed my bliss,” as Joseph Campbell would say. That’s a remark that is widely misunderstood. I mean, and I think he meant, that you should determine what it is that is really to the point. I must get at what is really to the point in my own life, in my world—in my limited world, and in my larger world. And encourage that to evolve.

That point must have changed over the years. What is it now?

I want to understand better and better what the old teachers were getting at, and to set that forth in the most relevant way I can for people today, for my readers.

You’re speaking of ninth-century China?

Absolutely.

It’s like you’re going forward and backward at the same time. You’ve been at the forefront of Zen in the West for fifty years and you’re extending yourself way back.

No, I’m not extending myself back. That back is extending itself through me. It would be most gratifying if I could really, really get the sense that I am talking their language in modern times.

Why have you gone all the way back to China, skipping the history that’s in your more immediate lineage, not to mention all of Japan?

I have four teachers, you know. Senzaki Nyogen Sensei, Nakagawa Soen Roshi, Yasutani Hakuun Roshi, and Yamada Koun Roshi. And their words come to my lips frequently as I speak, and they come to my fingers frequently when I write. I think of them often and their pictures are on my walls. I haven’t skipped them. But the real brilliance of our tradition runs from about 700 to 1200 C.E. I will quote Yuan-wu, for example, who is the editor of The Blue Cliff Record, but he too is commenting on the old teachers. I will quote Soen Roshi, or Yamada Roshi, who also are inspired by the old T’ang period teachers. And I honor Dogen and the early Kyoto teachers and Hakuin. But again there is no comparison. The T’ang period was an extraordinary time, you know. There were dozens of great teachers at any one time. Dozens of them. Teachers who would outshine anyone today. And they were in touch with each other though an uncanny kind of bamboo telegraph.

What is it they offer you?

They know “why the sea is boiling hot and whether pigs have wings.” Our task in the dokusan room is to bring those old guys to life through our koan study. Our task in dharma dialogue, or dharma encounter, is to try to do it ourselves. But it’s pretty feeble, compared to theirs. There’s nothing in contemporary Zen that will survive much beyond the moment. People may remember one or two little snippets of wisdom, but these won’t have the pungency and the depth and the living dharma quality that the old dialogues have. There were dozens and dozens and dozens of great monasteries in China, which were filled with monks for, say, five hundred years maybe, and they had meetings every night. How many hundreds of thousands of dharma encounters that amounts to, I don’t know. I have a collection of koans which has only five thousand. And of the five thousand, we study only a fraction—the crème de la crème, so to speak. I don’t want to imply that every encounter was a brilliant one; even with Chao-chou, say, not every encounter was so brilliant as his encounter with the monk in case two of The Blue Cliff Record where he quotes, “The supreme way is not difficult. It simply precludes picking and choosing.” Then they have this wonderful dialogue after that. Certainly not every dialogue worked that well, but a great many did. It’s my job to bring them to life—their perennial truths to life—and to help people embody them.

You’re talking about a culture of awakening, in which the monasteries were the sources of, and containers for, energizing and making possible this flourishing. How can we as laypeople do this?

You’re talking about coming together every single night of the week. Are we just going to say, “We’ll do our best to maintain and convey the voices of the old teachers, but the world is demanding something else.” Or do we say, “Wait a second. How are we going to create our own culture of awakening? And can we do it this way?” I think we’re faced on a large scale with what monks faced over a short period of time, when Buddhism was banned in China. What happened during that time? They were obliged to take off their robes and lie low, not identify themselves as Buddhists. They had to go into a holding pattern, so to speak.

Why compare this time of great religious freedom—at least in our own society—to a time when Buddhism was banned?

It’s not that Buddhism is banned today, but there are many, many influences that provide a setting that is not conducive to any great flowering. I read many books when I was interned during the war. The three most important were Blyth’s Zen in English Literature, Spengler’s Decline of the West, and Veblen’s Theory of the Leisure Class. With the influence of Spengler, I am quite content to live in this mappo period—this dark age. The point is that this is where we find ourselves. So we need to blunder along and work out what is possible. We face the degeneration of the dharma and a degeneration of human values. We also have the advantage of freedom to work things out.

Are you at all optimistic about the future of the world?

No. No, I’m not. I think we still have a ways to go down.

And then can we rise from the ashes?

I don’t know. But as Archy would say, “Wotthehell!” Let’s give it our best shot.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.