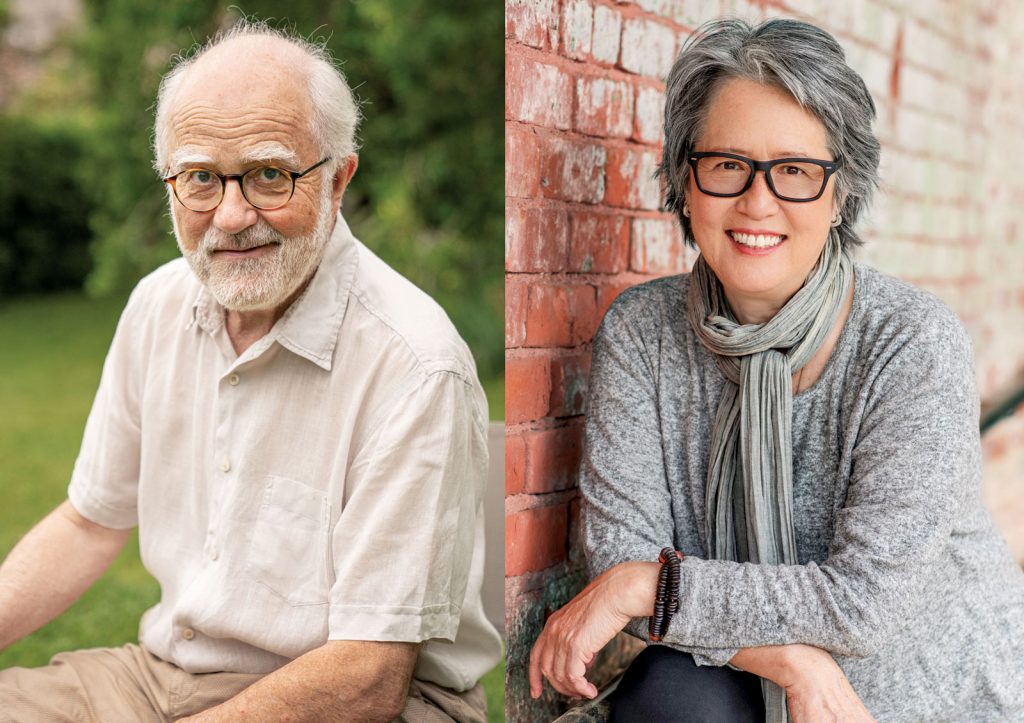

James Shaheen (JS): Ruth and Stephen, you both talk a lot about voice. Ruth, your novel The Book of Form and Emptiness is full of voices. There’s a cacophony of voices, and objects speak, and the main character is trying to find his voice. And Stephen, you’ve played with the notion of right speech as voice.

Stephen Batchelor (SB): We’re all familiar with the idea of the eightfold path and right speech. And the way it’s normally presented is in terms of what is morally, ethically good speech. It’s about speaking gently, truthfully, and honestly, and that’s important. But the word normally rendered as “speech” in Pali is vaca, which is a cognate of the Latin word vox and the English word voice.

So I started thinking of it not as speech but as voice. The person who enters the eightfold path, as the early texts say, becomes independent of others; then the practice becomes about finding your own voice. Meditation allows us to see how the voices we have internalized from our parents, political leaders, and religious teachers inform the way we speak and think, and thereby it opens up a space in which we’re not just vocalizing what our community believes and says.

And if we have an aspiration to be, let’s say, a writer or someone working in a creative field, then we’re constantly seeking to differentiate our own particular voice. It’s really about finding one’s own truth, one’s own authenticity, and also finding a kind of honesty within life. We have to be able to trust the intuitions and deeper feelings that we don’t really understand or even feel terribly comfortable with.

It’s almost a mantra of the creative writing world, finding your own voice, not deriving it from your favorite authors. It’s an ongoing process. But it’s a journey that is part and parcel of this eightfold path.

Ruth Ozeki (RO): As a novelist who works very often with characters who are autobiographical, I sometimes think of the novel as being a thought experiment and the self as being not just a fixed permanent entity but an array of selves that are constantly changing. That’s what my characters are. For me, the process of writing is a kind of performance art, of listening to all those voices, including the villainous ones who are constantly trying to make me shut up.

We hear a lot of villainous voices these days. We’re so completely overwhelmed by media and social media. And there are many, many voices in the world right now, and it’s very confusing. It is a cacophony. In my fictional worlds I try to inhabit those voices and put them in conversation with each other and see what emerges.

We think of a book as being an object: “This is my book.” But the book that James reads and the book that Stephen reads are two different books, which are both completely different from the book that I wrote. I wrote A Tale for the Time Being in 2012, and that Ruth Ozeki doesn’t exist anymore. You might have just read the book yesterday. It’s a way of speaking across time. The process of reading and writing is a collaborative effort. We’re not making a singular book, we’re making an array of books, and everyone who reads a book is going to be reading something slightly different. So that, too, is a creative act, a generative act. That kind of conversation is why writing is wonderful to me.

JS: I hosted a podcast with Arthur Sze, and he spoke similarly about his poetry, that the person who wrote it back then, and the person who wrote it now, and the person who’s reading it then and the person who’s reading it now, even the same reader, these are different voices and different people experiencing the same text.

SB: I have had the experience more than once of reading a quote in another person’s book and thinking “Well, that’s quite interesting,” and then looking up the source, and it turns out to be my voice. In other words, I didn’t recognize my own voice. There’s a weird sense of dislocation. But I think it makes the point that Ruth is communicating to us. We’re attached to the voice being “mine,” but it’s not really mine, except in a rather loose, conventional sense.

It is bizarre where voices come from. Carl Jung wrote, “People don’t have ideas. Ideas have people.” And as a writer, I often become spookily aware of that. There’s my mind saying “I’ve got to finish this chapter. I’ve got to work out how to say this.” And I get stuck in that place. But when I go off and do something quite different, some sentence forms by itself; something comes to me that I probably wouldn’t have figured out with my intellect.

There’s a source of language bubbling up within me, outside of my ownership and control. What I do as a writer, in many ways, is simply hold that space and create a channel whereby these voices can be heard. It’s a very strange business. I love writing books, because it’s a basically a journey into the unknown. The actual formulation of words, and ideas and things I’ve never thought of, come through by what strikes me as the logic of the text. I follow, I surrender to that logic, and I allow that to come forth, and that, to me, is magical.

I’m very interested at the moment in trying to find a Buddhist equivalent of creativity. I think it’s the iddhis or the iddhipada, what is usually translated as “magical powers,” meaning you can walk through walls and you can fly through the sky, and you can become one or become many, and so forth. Buddhist traditions often take those things literally. Particularly in the early tradition, this is actually a very basic practice. I think that iddhi refers to creativity, and creativity is a magical art. There’s a challenge for us, or at least for me, to re-own creativity as an explicit part of the practice of dharma.

RO: It reminds me, Stephen, of Hee-jin Kim’s book Eihei Dogen, Mystical Realist. Taigen Dan Leighton wrote the foreword, in which he proposed that sitting zazen is performance art. Zazen is a goalless practice, but when we sit, we are manifesting our buddhanature, becoming one with it. That is a type of performance art, and it is inherently creative.

Meditation is a generative, creative act. I’ve always thought that was beautiful. In the sangha, as we move around, make offerings, and do prostrations, we’re collectively performing. We’re inhabiting the Buddha-body as a community, and expressing it endlessly through the rituals and language passed down over time. It’s constantly being changed. It’s constantly being enlivened and reimagined.

“When we sit, we are manifesting our buddhanature, becoming one with it. That is a type of performance art, and it is inherently creative. Meditation is a generative, creative act.”

SB: As you’re speaking, I’m thinking of the philosopher Judith Butler’s conception of performative identity. Self is a performance. It’s how you present yourself in the world, how you communicate: that’s what you are. The Dhammapada, verse 80, says,

Just as a farmer irrigates a field,

as a fletcher fashions an arrow,

as a carpenter shapes a piece of wood,

so the wise person trains the self.

In other words, contrary to the idea that Buddhism is about getting rid of the self, it’s about understanding self as a work in progress, as an ongoing performance that is constantly unfolding, an unfinished project.

And there is something liberating about that, because Dan Leighton gets us out of the idea that all religious activity is somehow repetitive, that it’s keeping a tradition going by doing the same thing. There is room for that; the danger is if that becomes normative, then the tradition is stuck. But we can hold that structure in a way that actually liberates us to perform in our lives more wisely, more compassionately, more creatively.

JS: You’ve both talked about the dark side, places where people are reluctant to go, and Ruth, you certainly take us there in your book. Stephen, you have said that the creative act, giving up control and acting creatively in the moment, entails some degree of risk due to the uncertainty that we face.

SB: We find ourselves confronting life situations, often situations of great suffering, of great difficulty, of great conflict. I might have prepared myself and gotten as much information as I can, but at a certain point I have to say something, to do something, and often it’s very difficult. But once we do, you often find yourself taken over by a flow of words, physical gestures, or whatever it might be. And this is the source of the voice that is outside of us, beyond our ownership. It doesn’t seem to be coming from you but rather seems to have been allowed by your being willing to take a risk rather than just repeating platitudes of the tradition or saying the right Buddhist thing. But we can never be assured of being right, we can never be sure that this is the good thing to do, because we cannot possibly see the consequences and the outcomes of our acts.

RO: I’ve always felt that I write from remorse, that most of my writing happens because I’ve done something or said something that’s potentially harmful, that might have hurt somebody. I have that seed of remorse; then I sit with that and try to figure out: how did that happen? And then I start to perform that, to find the voices, and that performance turns into a novel. That’s certainly how the first novel came, and I think subsequent novels have come in the same way.

The act of doing anything, just living, being alive in the world, is fraught. How do we make sense of that? How do we examine that in ways that allow us to lead a life where we do no harm? Fiction writing looks at these ideas, in the same way that when we meditate, what comes up so often are the terrible things that we’ve said to somebody. The voices of remorse are constantly there. My process of examining these things takes a very long time. I’m glad I have this practice, because it allows me to do it. I don’t know how I would do it without having both the writing and the Buddhist practice together. The two are very helpful and synergistic in that way.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.