Michael Imperioli has a knack for playing mobsters and villains. Best known for his roles as Christopher Moltisanti on The Sopranos and Dominic Di Grasso on The White Lotus, the Emmy Award–winning actor has made a career out of exploring addiction and afflictive emotions on-screen.

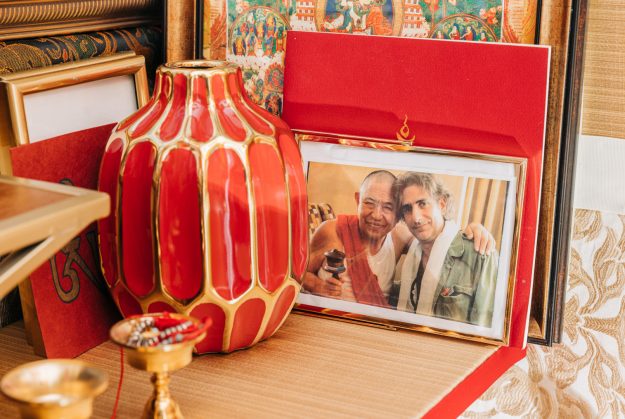

Off-screen, though, Imperioli is a committed Buddhist practitioner. In 2008, he and his wife took refuge with Garchen Rinpoche, and during the pandemic, they began teaching online meditation classes together, exploring Tibetan Buddhist texts like The Thirty-Seven Practices of a Bodhisattva. Though Buddhism no doubt influences his creative work, Imperioli prefers to focus his practice on his everyday life. For him, Buddhism offers a way to liberate harmful emotions and cultivate patience and compassion on a day-to-day level.

In a recent episode of Tricycle Talks, Imperioli spoke with Tricycle editor-in-chief James Shaheen about the dangers of the instrumentalization of Buddhist practice, what The White Lotus can teach us about craving and dissatisfaction, his relationship to his dharma name, and whether he believes that liberation is possible in this lifetime.

James Shaheen (JS): You’re best known as an actor, most recently in The White Lotus and famously in The Sopranos, but people may not know that you’re also a devoted Buddhist practitioner. How did you first come to Buddhism?

Michael Imperioli (MI): When I was a teenager, I started reading Jack Kerouac, who knew an awful lot about Buddhism. I mean, if you read his poems, like The Scripture of the Golden Eternity, you really see the depth of knowledge he had about dharma. I was very curious about Buddhism through his writing, so I bought a copy of the Diamond Sutra at St. Mark’s Books [in New York City’s East Village], and I really couldn’t penetrate it. Buddhism stayed somewhere in the back of my mind until much later.

In 2007, my wife and I started going to Jewel Heart, which was in Tribeca at the time, and Gelek Rinpoche was teaching there. That was the first time we went to a Buddhist teaching, and he was our first teacher. Shortly after that, we ended up taking refuge with Garchen Rimpoche. It was funny, because when my wife and I first walked into Jewel Heart, we realized we had both been there in the ’80s when it was Madam Rosa’s, which was a very decadent late-night nightclub.

JS: I remember that. You’ve come a long way.

MI: No mud, no lotus, as they say.

JS: Absolutely. I’ve heard you say that you came to Buddhism during the height of your success when you felt that something was missing. So what was missing?

MI: Maybe it’s not so much what was missing but that there was no ultimate satisfaction in the success that came. I spent my late teens only pursuing acting. I didn’t do anything else. I barely traveled, I was in New York, I did every job I could. I really wanted a certain degree of success, and I was driven toward that. And when that success did come, I realized that it wasn’t an end unto itself. I felt intuitively that what was missing was on a spiritual level—that there was a wisdom that was lacking. Just doing another successful TV show or winning an Academy Award wouldn’t be the answer.

I started exploring a lot of different spiritual paths before Buddhism, not really committing to any, reading books and going to different meetings and centers. I would read stuff like Krishnamurti, and when I was reading the book, it made a lot of sense. Then the book would be over, and I just felt like, “OK, now what?” There wasn’t really a practice to implement in your daily life. And then, when we stumbled into Jewel Heart, I saw the potential for a path and a practice.

JS: You mentioned your ambition and your desire to succeed in your career as an actor, and I remember many years ago, you sat on a panel with Gelek Rinpoche and Philip Glass. Philip said that the very qualities that made him a success professionally were the same that he applied to his practice: attention, focus, discipline, and creativity, among others. Has that been the same for you?

MI: Yeah, ambition has a negative connotation in some ways, but to succeed in anything, let alone an art form, you need a lot of tenacity and perseverance and discipline and passion and creativity. A lot of those are positive qualities, admirable qualities even. Practicing Buddhism takes a lot of discipline, and it takes a lot of perseverance, commitment, open-mindedness, and honesty. I agree with Philip on that.

JS: You know, I met you after that panel, and I interviewed you in 2009. I’ve been listening to your recent interviews, and it’s pretty amazing to hear you talk about your practice nearly fifteen years later with such commitment and depth. It made me realize that it helps me to see change in others that I often miss in myself. Do you ever feel that way?

MI: Yeah, especially with my wife, because we got into it together, we practice together, and we talk about it a lot. It’s a big part of our lives. I see it in her. I see it in simple ways, like when somebody annoys you, you have an awareness that somebody’s annoying you.

When you behave in a way that lets the afflictive emotion of anger get the best of you, you see that and make amends and realize that it’s not what you want to do. I mean, I see the discipline she has and the commitment to it [in reading Buddhist texts]. That’s very clear. But in those simple, day-to-day ways, I see the practice at work. And it’s very inspiring to me to see those changes.

JS: What sort of changes do you see in yourself in your own day-to-day?

“Maybe it’s not so much what was missing but that there was no ultimate satisfaction in the success that came.”

MI: You know, I find that more positive people come into my life—kinder people, more generous people, more compassionate people. And that’s amazing. Ultimately, the practice is bringing awareness to your existence, second by second, day by day: What am I doing in this moment? What am I thinking? I went through most of my life justifying my emotions and my reactions: “I did this because they did that. She took too long in the line in front of me at the coffee shop, and now I’m angry.” We can justify those emotions all the time, and that’s fine. But you’ll be stuck there. Those things don’t just go away.

JS: Often I think about Buddhist practice in terms of becoming a kinder, more compassionate person, and I don’t think that’s a modest goal. But I recently interviewed Anne Klein (Rigzin Drolma), and she said she was challenged by her Dzogchen teacher when he asked her, “Do you have confidence that you can achieve liberation in this lifetime?” I’m still focused on not snapping at my partner or the people I work with, and I consider it a victory when I have the intelligence and poise to make a decision not to be that way. And yet, sometimes I go back to Anne Klein’s teacher’s question: Do I believe I can be free? Does that ever come up for you?

MI: First, I agree with you that it’s not a modest aspiration to work with those afflictive emotions and become aware of them. I think liberation is possible in this lifetime, but it takes an awful amount of commitment. I’m confident that it’s possible; I’m not confident that I’m going to get there. But I don’t really think about it that much.

Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche once said to his sangha, “So you become enlightened. Then what?” He likens enlightenment to being present at your own funeral, particularly the idea of “you” with this ego mind becoming enlightened. They’re kind of conflicting because enlightenment is the opposite of that. He’s almost saying you can’t really have your self and your ego and be enlightened.

Enlightenment is not this better version of you. It’s not Clark Kent becoming Superman. It’s something else. One of the mahasiddhas said, “I am not really impressed by someone who can turn the floor into the ceiling or fire into water. A real miracle is if someone can liberate just one negative emotion.”

JS: On the note of negative emotions, you play Dominic Di Grasso on The White Lotus, and he seems like a case study in dissatisfaction, addiction, and regret. Dominic can’t prevent the mistakes he has to make, although he pays for them in cash. I’ve found that practice can offer an opportunity to intervene, yet most people won’t come to the practice. How do you think of this in terms of the bodhisattva vow? Or is that too crazy a question?

MI: No, it’s not a crazy question at all. The bodhisattva vow is a really big commitment. [laughs]

JS: Kind of like enlightenment.

MI: Yeah. Maybe when you first hear about Buddhism, you think that there’s a way to reach nirvana or some place where all the suffering is gone. Then you take a bodhisattva vow, and you realize that whatever that state is, you’re not going to get there until everybody else gets there, and you’re hanging around for everyone else.

I think The White Lotus really shows the habitual tendencies that become so ingrained through your own karmic imprints from past lives, through your DNA, and through the learned behaviors that you saw in your younger years from your parents or the culture you were in. Those things can really stay with a person and stay in a family unless something cataclysmic happens or some kind of light bulb goes off—or both, maybe at the same time.

The White Lotus is interesting to me because you have very, very rich people in the most opulent, luxurious god realms, and they’re all miserable. When you don’t have those things, you might think that it would make you really happy to live like this or travel first class and stay in the best hotels. And here we have a story of these people who actually do that and are not very happy at all. There’s momentary happiness and fleeting pleasures, and yet there’s still dissatisfaction. Something is not being fulfilled.

JS: Right. There’s an interesting experiment I did when I was much, much younger. I found this apartment in New York, which was no mean feat at the time, and I really loved it. I had a view of the Hudson River, and the apartment even had a window in the bathroom, which in New York isn’t guaranteed by any means. I remember thinking, “I wonder how long before I take this for granted.” I wasn’t yet a Buddhist; I didn’t have a practice. But it occurred to me that we fall for it every time. We think, “Just this will make me happy.” And in The White Lotus, it’s really clear that we fall for it every time.

MI: Yeah, how long did it take before you took it for granted?

JS: I think it must have been about six weeks, and all of a sudden, I was in a mood again. I didn’t care about that window. I didn’t care about the Hudson River. But when I see the character you played, it would be easy for me to hate him if I didn’t also identify with him. He wants his wife back, and yet he’s in the throes of addiction—he can’t help himself, and he can’t help his son. It was such an accurate description of the samsara that we all live in, and again, I think that practice can interrupt that. Or it’s a possibility anyway.

MI: It is a possibility. But even with practice, those ingrained behaviors, especially addiction, are very hard. Pema Chödrön talks a lot about how a lot of the path is one step forward, two steps back. Maybe one day you go one step forward and only one step back, and you should rejoice in the fact that today it was only one step back. That’s progress. I think practice can help because to practice Buddhism requires real honesty with yourself. You really have to have a bold, honest view of your own mind. People can uncover this through psychotherapy with psychologists and psychiatrists. But with Buddhist practice, it’s in a different way, sometimes a mundane, day-to-day way. You really have to make a commitment to being honest with yourself, and that’s sometimes very hard.

JS: Yeah, I’ve found that sangha and a teacher are essential in being honest with myself. Sometimes a teacher can say something that cuts right through your fabrications. I remember once I was harping on something, and my teacher looked at me and said, “Why do you care so much?” And all of a sudden it shattered. I was sitting there seeing myself as this repetitive person harping on the same thing, and I had to really consider, why did I care so much? Practice is important in relationship with others and with a teacher, without which I don’t think I’d have made any headway at all.

MI: Oh, same for me. I don’t think it really exists outside of that.

“The goal of Buddhism isn’t to make you a better actor. That’s like taking a Ferrari to drive next door.”

JS: In addition to being an actor, you’re also a musician. Can you tell us a bit about your band, Zopa?

MI: Zopa is an indie rock trio that was formed in 2006. We took a hiatus when I moved in 2013 for about seven years, and then two and a half years ago, we started playing again. I play guitar, and I sing some of the songs. It’s a very collaborative group. We’re influenced by a lot of the New York bands from the ’70s like the Velvet Underground and Lou Reed, as well as a lot of ’80s post-punk and ’90s indie rock.

Over the years, there have been some Buddhist themes in the songs, and we have a new song that includes the Seven Line Prayer of Guru Rinpoche in Tibetan. There’s something cool about playing those songs live—those mantras and prayers have a certain frequency and resonance that I think might touch people in positive ways.

JS: The name of your band is also your dharma name, Zopa. When did you receive the name, and how has your relationship to it changed over time?

MI: When I took refuge with Garchen Rinpoche, I got the name Konchog Zopa Sonam. Zopa means patience in Tibetan, and the day I took refuge, he said, “Patience is the key to your practice because when you lose your patience, you lose your love.” At the time, I was still very new to Buddhism, and I took that as a pithy Hallmark card nugget—I didn’t really take it to heart.

Years later, I said to myself, “The day you took refuge with him, he said this to you. Maybe you should give it a little bit more importance. Maybe you should really look into what it means for patience to be the key to your practice.” Since then, I’ve started to take it more seriously and really focus on it as much as I can or as much as my awareness allows me to.

Trungpa Rinpoche said that if you’re a dharma practitioner, patience is an obligation. It’s not just something you do because you want to be kind. It is an obligation. Not only that, but it’s also an opportunity to practice. When you feel yourself becoming impatient, you can become aware of that and choose to bring some patience into the situation. These little annoyances become opportunities for practice.

JS: We recently had the interdisciplinary artist Meredith Monk on the podcast, and she said that a lot of our artistic practice is waiting and trying to get out of the way. Does this resonate with you, and how do you think about the creative process?

MI: God, yeah. Especially on a movie set, you spend most of the time waiting. But also with writing, if you’re working on a writing project that’s going to take some time—let’s say you set up a schedule to write Monday through Friday from 10 to 3—chances are you’re not going to be literally writing fingers on the keyboard for five hours, and there might be a big chunk of that time where nothing’s happening. You’re not really waiting for inspiration because you can’t wait for inspiration—you’d probably wait forever. But you have to trust that there’s some other process going on subconsciously and that for those hours that you’re there, there is some kind of alignment where you’re in tune with the story or the character. Even if you’re not actively writing or actively imagining it, somehow, your consciousness knows that that period of time is related. You have to trust that, and there’s a lot of waiting involved.

JS: More generally, how does practicing Buddhism shape your artistic work?

MI: Typically, I don’t like talking about this because the goal of Buddhism is not to make you a better actor. That’s like taking a Ferrari to drive next door. But I do think that meditation can help with focus. Art demands a certain intensity of focus and concentration, be it performing onstage as an actor or as a musician, sitting down writing, or acting a scene. The more focused you are in the moment, the better, and I definitely think meditation can help with that.

JS: So in other words, it’s an ancillary and unasked-for benefit. But you pointed out something very important, I think: the instrumentalization of our practice in order to get something. Any of us can fall into that.

MI: Yeah, back to Trungpa Rinpoche: it’s kind of like being present at your own funeral. The fact that this 2,500-year-old tradition is still in the world and there’s still a lineage and a connection to that wisdom is so unbelievably precious that to instrumentalize it for some worldly purpose really runs counter to it. If you’re making a commitment to practice, at some point, there’ll be shifts in everything: in the way you interact with and perceive the world. They may be little shifts, but they’re there.

♦

Listen to the full conversation on Tricycle Talks here.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.