IT HAS BEEN SAID that without monasticism there is no Buddhism. When the first sangha—group of followers—began to grow around the Buddha there was, of course, no distinctly “Buddhist” form of monastic practice. The monasticism that the Buddha developed took into account the needs of his disciples as well as the realities of his culture and society. This responsiveness to the imperative of time, place, and people is still the defining characteristic of Buddhist monasticism.

In Zen, each teacher in each generation is a buddha. Each teacher is in exactly the same position as the historical Buddha, dealing with the conditions particular to his or her students. After receiving the mind-to-mind transmission, a teacher is free to manifest the dharma in accord with the imperatives of the day, however those might be interpreted. Once the Buddhamind is realized, its actualization manifests as skillful means arising out of the immediate conditions encountered by the teacher.

In creating the Mountains and Rivers Order, the training matrix at Zen Mountain Monastery, we made a very clear separation between lay and monastic practice. This is a new phenomenon on the landscape of American Zen, one that goes against the grain of many New Age tendencies to synthesize all religious and spiritual teachings and practices.

From the beginning of Buddhist practice in this country there were people who wanted to experience traditional monastic training but rarely were they willing or able to completely abandon their worldly connections. As a result, a unique type of western Buddhist monasticism developed, an eclectic fusion where monastics maintained secular careers, married, and raised children. Because of this change, most of these modern Buddhist monastics did not get much experience with extended communal living, sharing their lives with other students, and studying continually with a teacher under varying circumstances—all vital and transformative aspects of monastic practice.

Most of the lay practice that goes on among new converts in America is a slightly watered-down version of monastic practice, and most of the monastic practice is a slightly glorified version of lay practice. At most Zen centers frequently nobody can tell the difference between a monastic and a layperson, except for the way they dress. Monastics usually wear black robes and lay practitioners wear robes of another color. Most American monastics live in the world, not in monasteries. They don’t shave their heads, and they don’t take vows any different from the vows that lay practitioners take. This results in ambiguity and confusion. To me, this hybrid path—halfway between monasticism and lay practice—reflects our cultural spirit of greediness and consumerism. With all the possibilities, why give up anything? “We want it all.” Why not do it all?

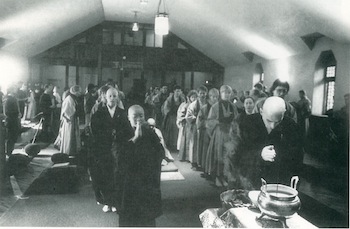

Within the Mountains and Rivers Order we accent the differences between monastic and lay training because the beauty of the relationship between the two practices depends upon those distinctions. You can’t have co-origination and interdependence without differences. If everything were the same, there would be no possibility of a relationship or, for that matter, realization.

Monastic practice and lay practice are and always have been in a dynamic relationship, one supporting the other. You would have a very short-lived lay practice without monasticism and a very short-lived monasticism without lay practice. That has been the history of the Buddha-dharma—2,500 years of it—with its vitality and lifeblood depending on the contrast, the contact, and the integration of the two streams.

The enlightenment of a monastic and a lay practitioner are not different. Both monastic practice and lay practice can result in deep, profound realization—one indistinguishable from the other. What are different are the respective occupations of monastics and lay practitioners, the difficulty of attaining realization, the depth and breadth of training, and the possibility of formally completing one’s study.

In the secular world, we have many responsibilities and gravitate in many directions: family, job, property, children, neighborhood. As one develops as a lay practitioner, one’s life takes place within the matrix of the dharma, but the main focus of lay life remains either on one’s family, on one’s career, or both. For lay practitioners it is difficult to receive consistent guidance. They do not live with a teacher or senior students and thus have no ongoing models for daily practice. The only time this is available to them is when they are able to do periods of residency or meditation retreats at a training center. The focus of a monastic’s life is the dharma itself. A monastic is married to the dharma. The major occupation of a monastic is the dharma. Nothing else. One hundred percent of the time, every day.

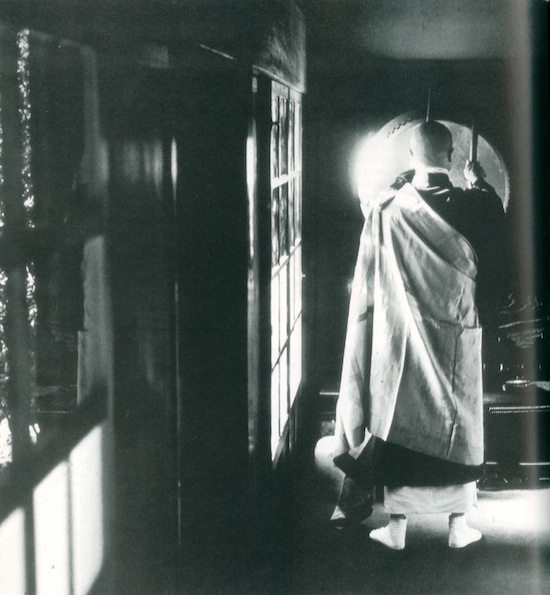

In traditional Zen writings, the term “monastic” is not used; rather, there is the word unsui. Unsui literally translates as “clouds and water.” Clouds and water are free. Clouds follow the wind, water takes the shape of the terrain. Nothing holds them back. If you try to stop a stream, it just builds up behind the obstruction and goes over it. The journey to the ocean is unstoppable. The biggest dam in creation can’t hold back the river in its flow. It is persistent, continuous, flexible.

Yet, in a practical sense, one can ask: “What good is a monastic?” Our society certainly posits that question, not just in relation to Zen monastics, or Buddhist monastics, but for monastics in general. What does a monastic produce? In a materialistic culture, where such incredible value is placed on productivity, what does a monastic contribute? What good is such a life? What is the relevance of a monastic to the world?

In his Asian Journal, Thomas Merton wrote:

Are monastics and hippies and poets relevant? No, we’re deliberately irrelevant. We live with an ingrained irrelevance which is proper to every human being. The marginal person accepts the basic irrelevance of the human condition, an irrelevance which is manifested above all by the fact of death. The marginal person, the monastic, the displaced person, the prisoner, all these people live in the presence of death, which calls into question the meaning of life. They struggle with the fact of death in themselves, trying to seek something deeper than death, because there is something deeper than death, and the office of the monastic or the marginal person, the meditative person, is to go beyond death, even in this life to go beyond the dichotomy of life and death and to be, therefore, a witness to life.

IS THIS, THEN, A LIFE OF TOTAL FREEDOM? From one point of view, those who haven’t renounced the world are caught up in the world, are holding on to the world, and are controlled by the world. They are not free to go from one place to another. They have responsibilities and obligations. At the same time, a monastic, following a strict schedule and bound by vows, is completely in the hands of the teacher in a way that no lay practitioner could possibly be.

Shukke-tokudo, the Japanese word for monastic ordination, literally means “leaving home,” giving up one’s last name and taking on a monastic’s name. Homeleaving is the defining characteristic of the monastic form, the heart of all the vows of a monastic. In homeleaving, monastics renounce their genetic lineage and enter into the family of the Buddha. Initiates are expected to be free of worldly obligations, have no dependents relying on them, and have no financial or personal debts, other than the infinite debt of gratitude for this life.

Bows made to our parents during the ordination ceremony are bows of appreciation and farewell: “Thank you for this life.” With monastic ordination, the relationship between the parent and the child completely changes. The child’s duty to care for the parents is replaced with a vow to serve all sentient beings, equally, without discrimination.

Leaving home doesn’t mean ignoring one’s family, however. That is one of the tremendous misconceptions about Buddhist monastic practice that persists in this country, one that I personally don’t accept and don’t practice. Yet Zen literature does present examples that seem to imply that leaving home requires cutting family ties completely. Master Tung-shan, for example, disregarded his mother when she became very old and asked to be admitted to his monastery. She was clawing at the door, crying for help. He wouldn’t let her in. She died, according to the story, of a broken heart. He wouldn’t let her in. The story then continues, telling how she was reborn in some heaven and thanked her son for not breaking his vows as a monastic. Well, I don’t buy it. If one takes a vow to save all sentient beings, surely that includes one’s own mother. She should not have to suffer under the handicap of giving birth to a monastic. She deserves, at least, an equal opportunity with the rest of sentient beings.

At Zen Mountain Monastery a monastic can either practice celibacy or be in a stable monogamous relationship. In my experience, the argument that monastics have to be celibate falters because there are very few people mature enough to enter that type of practice. There are exceptions; there are a few people for whom celibacy works. But, in general, forced celibacy leads to frustration, bitterness, and regrets. To practice a stable relationship there has to be a willingness to grant complete spiritual freedom to one’s partner. The clouds and water image persists within the relationship: the two people are related, yet free. Although a monastic may have a life companion, that does not necessarily mean they will share the same home or raise a family together.

The monastics at Zen Mountain Monastery agree not to procreate. If they have a child, then they’re a parent, not a monastic. Having brought another life into this world, to take care of that life becomes the imperative. They have to take off their robes and raise the child until he or she is independent. Only then can they put their robes back on and continue their monastic practice. Similarly, if someone has unfinished business with their family, they need to take care of that before taking monastic vows. This doesn’t mean that monastics ignore their parents or other family members. If a person is in need, and they’re the most appropriate one to give them nourishment and take care of them, it’s fine for them to do it. I like to think of our practice as a very human endeavour.

Every fifth day the monastics shave their heads and chant the Gatha on Shaving the Head. The gatha says:

In the drifting, wandering world, it is very difficult to cut off our human ties.

Now, I cast them away and enter true activity.

It is in this way that I express my gratitude.

As I shave my head, I renew my vows to live a life of simplicity, service, stability, selflessness, and to accomplish the Buddha’s Way.

May I manifest my life with wisdom and compassion,

And actualize the Tathagatha’s true teaching.

These five life vows distinguish the Mountains and Rivers Order monastic from a lay practioner.

The vow of simplicity has to do with renouncing worldly possessions and stripping yourself of distractions. It means burning your bridges behind you. Simplicity is the letting go of all the “stuff” we hold onto. It includes a vow of poverty. Monastics receive no salary and are not permitted to own any property. There are no inheritances, no safeguards. As a result, they become totally dependent upon the lay practitioners. If suddenly all the lay practitioners disappeared, the monastics would have to go out and work in order to feed themselves. Food and the shelter are provided by the lay sangha, and in return the monastics offer their service to the community in a spirit of selflessness. This mutual dependency between the monastics and the lay practitioners creates an essential part of the dynamic. It allows the practice of true giving.

Central to the vow of service is giving your life away to others. Monastic life is being a servant to the Three Treasures—to the whole world and to all beings. It is a pure bodhisattva vow. Monastics serve the teacher, the fellow monastics, the community. They respond to the needs of the people as circumstances unfold; their own life and needs become a secondary focus.

The vow of selflessness is the practice of forgetting the self and realizing the ten thousand things. It is a vow of intimacy, a whole body and mind combustion of this life, a vow of realization and actualization of the Buddha way.

The vow of stability has to do with having completed the major changes in one’s life. That is, no vows, above the vow to the dharma, are functioning. There are no other, superseding responsibilities or obligations. This means that we are dealing with an emotionally mature adult. It is hard for a seventeen-year-old to be that resolved and clear in forming a commitment.

The monastics, with their dedication, are the continuation of this dharma. Their vows assure that the dharma of this monastery will go on, even after the buildings disappear and the mountain itself crumbles. No matter where, no matter how, it will continue. And it is for this reason that it has been so important to me, to my teacher, and to his teacher, to have completely dedicated monastics among our successors. On a larger, historical scale, the stability provided by monasticism directly effects the well-being and the vitality of Buddhism in general. Whenever there was a decline in the vigor and authenticity of monastic practice, there was a parallel weakening of the religion itself. The spiritual spark has somehow always found a sanctuary within monastery walls.

The last of the five Mountains and Rivers Order monastic vows does not say “accomplishing the Buddha Way,” as is usually said in Zen monasteries, but “accomplishing the Buddha’s Way,” that is, to live the life that the Buddha lived. The Buddha Way is the teachings of the Buddha. All practitioners make the vow to accomplish the Buddha Way. The monastic’s vow is to accomplish the Buddha’s Way, that is, to make real in one’s own life the life of the Buddha. To accomplish the Buddha’s Way is not a place. It is not a goal. It doesn’t have anything to do with time and space. It’s a continuum that goes back to the beginningless beginning, a continuum that proceeds into the far-distant future, that verifies the life of all buddhas and is the realization of all Buddhas.

The central continuity that we have had from year to year, over the past fifteen years, has been maintained by the monastics. The comings and goings of the lay practitioners are quite dramatic. People come into residency for a year or two and then they leave. Others appear. Stability rests with the monastics. It is paramount to understand that the dynamic of monastic practice/lay practice, the interpenetration of sacred and secular, is a two-way street. You can’t do it with one or the other alone.

When you have the two components, you have what it takes. The bee and the blossom are both necessary in order for the fruit to appear on the free. If there’s no cross-fertilization, you don’t get any fruit. If there’s no fruit, there’s no ripening. If there’s no ripening, there are no seeds. If there are no seeds, there are no succeeding generations. The interdependence between monastic practice and lay practice is the juice, the vital energy that will keep the dharma alive on this continent for many generations to come. It’s important that we, as the Western sangha, recognize our responsibility to these future generations of Buddhists. The imperative of 2,500 years of monastic practice challenges us. It lies in our hands

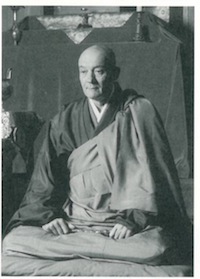

John Daido Loori is the abbot of Zen Mountain Monastery in Mount Tremper, New York. He is the author of Two Arrows Meeting in Mid-Air, published by Charles E. Tuttle Co., Inc.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.