WHEN THEY FIRST EMERGED in India in the fifth century B.C.E., Buddhist communities took a stubbornly antagonistic stance toward poetry. Early Indian monks and nuns subsisted on one begged meal a day, owned a robe, a bowl, and a razor, and spurned the arts as a fearsome distraction. Their early documents, all bone and sinew, condemn the arts as diversions from the clear stream of Buddhist practice. Suffering, samsara, the wheel of rebirth, and a potential release from the iron tongs of existence—these concerned the first Buddhists. As for poetry—its musical enthusiasms seemed a venal snare, distracting, disastrous. Fixing a cold eye on “unprofitable talk,” the Digha Nikaya, an early canonical text, enjoins against:

All manner of idle babble, such as: talk about kings and robbers and ministers of state: talk about annies and of fear, tales of fights: talk about food, drink, clothes, beds, lodgings, flower-garlands, scents, kinsfolk, and carriages: about villages, suburbs, towns, provinces, women, and soldiers: gossip of the streets and wells, and tales of ghosts: all sorts of talk: about the world and the ocean: of things existent and non-existent.

One might as well draw up an inventory of themes for poetry.

For Americans drawn to Buddhist practice by the hauntingly personal song and swift brushwork of China and Japan, this antipathy toward poetry seems baffling. But injunctions against art in the early Buddhist texts force some enchanting contradictions. You encounter Shakyamuni Buddha in their pages surrounded by a throng of listeners—monks, nuns, merchants, shy animals, petty gods, earnest ghosts, sprites, wild vapors, and so forth. Travelers of the Way, he announces, must flee ornamental language, for it will cast you into one of the fearsome hells; don’t mess with dancing girls, don’t burn incense, don’t loaf among flowers or wild grass. How can you toy with such frivolities when the human condition, stripped of ornament, is like sitting in a burning house? For the blink of an eye, art may conceal flames of grasping, anger, and false pride, but it surely fans them, and in an instant they leave a person scorched and withered.

These refreshingly tough documents recount the dangers that lurk among the human senses, illustrating them with harrowing examples. Yet when Buddha finishes speaking, the heavens open. Flowers rain from the sky, clefts in the earth give forth incense, divine lute-strummers seated on rainbows break out in song, and fabulous dancing girls appear in the sky. It is like a Grateful Dead concert, or one of those religious carnivals, the mela, that so splendidly characterize the Indian subcontinent. What’s more, the entire description occurs in metrical verse.

India as a civilization has for millennia produced ecstatic dance, amorous poetry, peerless music: it has fashioned sculpture, painting, and architecture in the absence of which the planet would seem insufferably forlorn. For India, not one of life’s facets could stand separate from its enactment in art, not yogic disciplines, not the most closely held love affair or the most antisocial cult of sex and sagacity—all found expression. Art and spiritual discipline met gracefully in the popular mind.

IN INDIA AN ANCIENT GATE divides verse from poetry. Writing came into India strikingly late, and virtually all information worth preserving was committed, over the course of several thousand years, to a vast webwork of verse. Even the words of Shakyamuni Buddha did not get written down until 80 C.E.—five hundred years after his Nirvana. As far back—literally—as memory goes, scholars and poets had devised sophisticated means for memorizing literature, fixing their entire culture in metrical verse. Eventually all this material prompted a distinction between high-culture poetry—what they called kavya—and those verse forms in which they fixed epic, science, politics, astrology, and liturgy. Such verse collections of non-poetry went by a number of descriptive names—shloka or gatha, for instance—that denote specific metrical patterns.

The Buddhist communities employed numerous gathas—verses recited at mealtime, funerals, or at ceremonial functions. Thanks to these recitations small crafted vessels of language—something close to poetry—began to slip through the back door of the monastic hall. Monks and nuns improvised verbal mind-honing devices or mantra. Haunting calls to vigilance reinforced the serious and sacramental approach to daily activities.

Monks, I beg you to remember,

Life and death are serious matters.

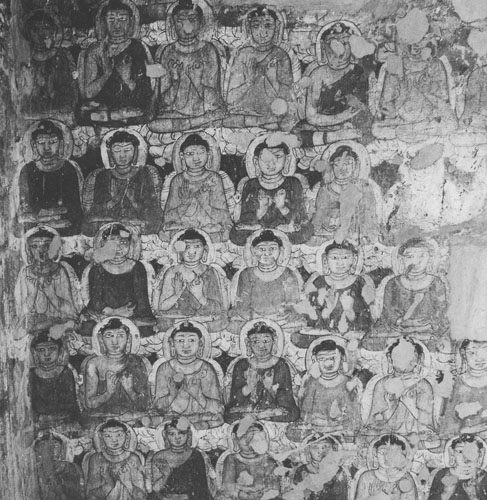

Despite the enjoinders against high art, some fine early poetry from India seems to have developed within the ranks of the Buddhist communities, alongside the functional chants. Not long after Buddha’s death, monks and nuns gathered in small communities, sometimes in city parks, often in wild isolated jungle retreats or mountain caves. And a few of them began to produce some remarkably sound poetry. There are two collections, the Theragatha, or Songs of the Monks,and the Therigatha, Songs of the Nuns.

The renunciants justified these poems as teaching devices, developed specifically to draw others toward Buddhist discipline. Some of the poems detail the solace of contemplative life pursued in wild, lonely settings, or thrill to the elegance of a homeless wanderer’s life. But the more interesting songs, especially those of the women, are longer. Confessional, dramatic, they follow a ballad like development, recounting the poet’s own story through a series of rebirths, in order to demonstrate why she has shunned the world of social convention, shaken off the claim of institutions, and taken the renunciant’s road.

Some give detailed accounts of the poet’s activities prior to entering the order—love affairs, marriage, children, village celebrations—luxuriating in all those orders of talk the early documents had pronounced “unprofitable.” But like an Anglo-Saxon ballad, in which some half-articulated unease behind the words suggests happiness is but prelude to tragedy, they mount with swift inevitability upon crisis, some dreadful event which strips the poet of everything. Children die. Flood ravages the village, or bandits the family. Starvation, earthquake, or political violence brings the poet to her knees.

Hopeless, grieving, torn—these poems depict a world bleak and unutterably realistic. Yet in the end, when the poems climax, they come upon a strange, nearly inexplicable thrill—a moment of triumph, personal empowerment. In the wake of tragedy comes unsurpassable insight. No mere personal misfortune has humbled the poet. To imagine it so would be vanity.

Rather, the trappings of existence are, every one of them, impermanent, inexorably subject to loss. Neglect of this truth is a tenacious clasp of illogic. Buddhist poetry begins here—with a resolute turning away from maya, the dream of this world.

DESPITE THE DIDACTIC INTENT of these hermit songs, by undergoing a subtle inversion they set the tone for India’s classical poetry, which arose around 400 C.E. and flourished during the height of Buddhist civilization. \Vhen I say inversion, I mean that what comes to distinguish classical Sanskrit poetry is not the triumph and grandeur of renunciation, the yogin’s insight, but a wistful lingering over the qualities of a fleeting world, an understanding that the very insubstantiality of things gives them their flavor. Perhaps only the Japanese have developed a comparable tradition, one in which poetry so delicately and bravely celebrates impermanence. A curious verse caps the Diamond Sutra:

Like stars,

like a lantern, some

castle of magic,

a dewdrop, or bubble—

like a dream,

streaks of lightning

or a cloud—

all things vanish

this way from the mind.

Sanskrit poetry took this for its tone, extolling in verse the planet’s wealth of delights, at the same time acknowledging their evanescence.

India’s classical poets accepted the renunciant’s insight; thus their best verse imparts a bittersweet flavor. Each poem is a brush stroke dashed across nothing—a stroke so transparent it seems all gesture, no substance. This is maya, what the Buddhist calls samsara, the stream of appearance. An eye blink makes it all vanish. But before it fades utterly the poet tries to set down a flash of tenderness, humor, mischief, grief—the poem a formal gesture into the Void.

Intimations of mortality shadow each poem. Even when explicitly erotic, lighthearted, careless, something forlorn stings the poem at its margin. Consider this, left by a Dharmakirti who mayor may not be the renowned Buddhist commentator:

A snatch of dream,

a juggler’s contrivance—

our hours in bed a mere flicker

before the dream bursts.

A hundred times I tell myself this,

but cannot forget

those eyes like the antelope’s.

Another poem comes even closer. What it depicts could occur in life only once, caught somewhere between the in-breath and out. Yet in the poem it comes as a deathless stroke—a moment cut into eternity.

This time let me

be the lady

you play the lover—to which the girl

protests

shaking her headbut eyes

wide as a

deer’s eyes she threads

a bracelet onto

his wrist.

I give a final poem. At a time when our planet’s large mammals confront extinction at an unprecedented pace, this one resonates with impermanence in a way its composer could scarcely have guessed at.

Rain slants steadily

through the night-bound

toddy-palm forest. Concealed

by huge fronds

the elephants, eyes

half open and trunks

slung over their tusk-tips

listen to the unending

downpour.

In the Buddhist centers that dotted the landscape of north India from the fourth through the twelfth centuries, poets and scholars collected these poems into large, well-organized anthologies. When marauding Turkish Muslims in search of land and booty began storming across India in the eleventh century, they targeted these centers of learning, smashing statuary and torching libraries. It spelled the end of Buddhism in India, and countless manuscripts disappeared or went up in flame. Those that survived surface occasionally in Nepalese or Tibetan monasteries where escaping Buddhists fled with them at great personal risk.

Not people only, but civilizations, even those that endure for a thousand years, are born, achieve glory, wealth, elegance—and die—die suddenly, alone and without solace.

Like a dream,

a streak of lightning

or a cloud—

This was the taste of poetry in Buddhist India.

SONGS FROM THE THERAGATHA

Songs of the Buddhist Monks circa 450 B.C.E.

This lady who cremates the dead

black as a crow—

she takes an old corpse and breaks off a thighbone,

takes an old corpse and breaks off a forearm,

cracks an old skull and sets it out

like a bowl of milk

for me to look at.

Witless brain don’t you get it—

whatever you do just ends up here.

Get finished with karma, finished with rebirth—

no more bones of mine

on the slag heap.

—Mahakala

Abandoning his house,

mind just drifting,

rooting his snout through mud

like an impatient hog—

here comes the fool

flickering through yet another

womb.

—Belatthakani

Come Nandaka,

let’s give the lion’s roar

face to face with all buddhas.

We have done it,

what the wakeful sage

spurred us on to—

we’ve shattered the manacles!

—Bharata

I made a hut

from three palm leaves by the Ganges.

Took a crematory pot

for an eating bowl,

lifted my robe off a trash bin.

Two rainy seasons passed and I

spoke only one word.

Clouds came again

but this time the darkness

tore open.

—Gangatiriya

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.