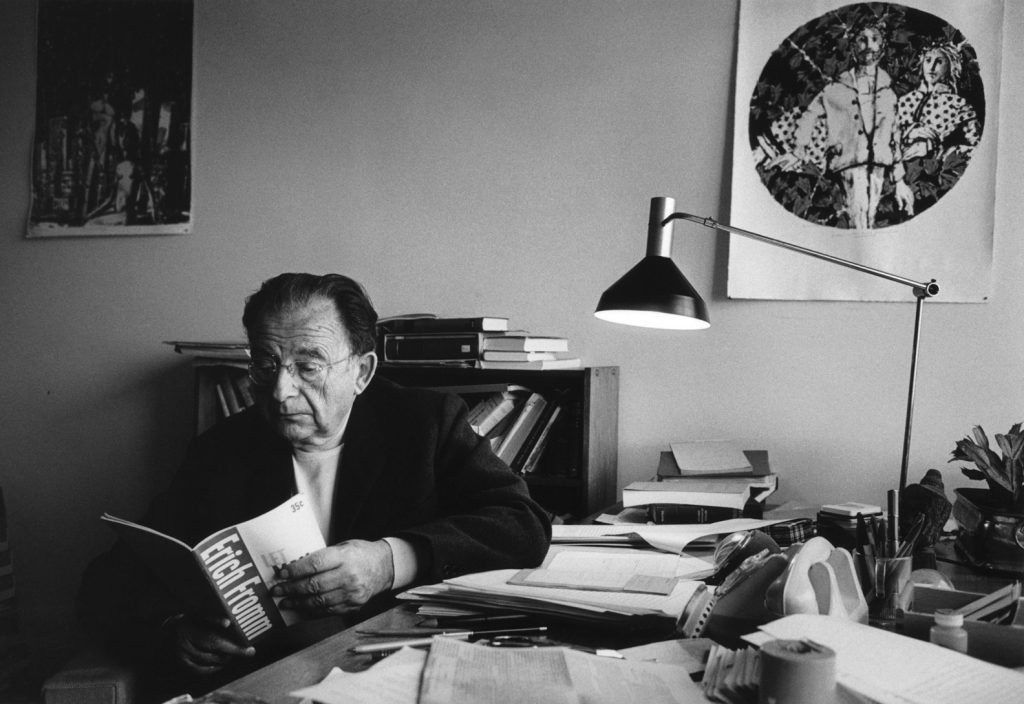

As the popularity of mindfulness has continued to grow in the United States, so have debates about (among other topics) whether it is a cure-all for the ailments of the modern condition or rather pacifies us into accepting the injustices of a consumerist system. But many decades ago, the psychotherapist Erich Fromm (1900–1980) already warned against the possible misuses of Buddhist practices when appropriated by the wider culture. At the same time, he thought that a meditation practice many today would recognize as “mindfulness” could free individuals from authoritarian thinking and provide healing for the ills of contemporary society.

Fromm’s life is an illuminating example of 20th-century Anglo-European interest in Buddhist traditions. As an intellectual who helped shape the “Zen boom” of the 1950s, he was very much a man of his time and yet also way ahead of it, predicting the advent of our present-day mindfulness movement before the word “mindfulness” was on anyone’s lips.

Fromm’s “humanistic psychoanalysis” approach in the mid-20th century presented a holistic view of human beings as shaped not only by internal psychodynamics but also by the wider sociocultural context in which they live. In addition to pursuing clinical work, Fromm served an active role as a sociologist, cultural commentator, philosopher, and activist. His writings, which blend neo-Freudian and Marxist thought, stand as some of the first entries in the field of political psychology.

Fromm had also always been curious about religion. Born in 1900 to Orthodox Jewish parents in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, he contemplated becoming a Torah scholar when he was a young student. He wrote his PhD dissertation, on the social psychology of Diaspora Judaism, at the University of Heidelberg under the famous philosopher Karl Jaspers and Alfred Weber, brother of the seminal sociologist Max Weber. From his early career, he worked with other luminaries of his day, including Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse at the Frankfurt Institute of Social Research, which was hugely influential in the development of 20th-century critical theory.

After Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, Fromm fled first to Geneva and then to New York City, where he helped establish a new home for the Frankfurt Institute at Columbia University. There he continued to develop his humanistic psychoanalysis and theory of “social character,” ideas that he later applied directly to the topic of religious traditions in his 1950 book Psychoanalysis and Religion.

In this work, Fromm revised the dismissive theories of religion represented by his two central intellectual heroes, Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud, to posit that all human beings possess an inherent and inescapable psychological need for what he called “a frame of orientation and object of devotion.” This need could be twisted by “authoritarian religions” that taught submission to a higher power—a submissiveness that could also be exploited by state regimes demanding blind adherence of its citizenry or an economic system that, for example, cultivated slavish idolatry to the almighty dollar. For Fromm, “humanistic religions” could offer liberation, leading people to look within for salvation and to celebrate the human potential for love and creativity.

“One of the best examples of humanistic religion,” Fromm wrote in Psychoanalysis and Religion, is “early Buddhism . . . a religion in which there is no God, no irrational authority of any kind, whose main goal is exactly that of liberating man from all dependence, activating him, showing him that he, and nobody else, bears the responsibility for his fate.” Fromm seemed to be even more enthusiastic about Zen Buddhism, which he saw as “expressive of an even more radical anti-authoritarian attitude.”

However, Fromm’s perception of Buddhist traditions was not acquired through contact with the actual Buddhist communities across Asia who, for example, propitiate divinities on a daily basis. Instead, beginning as a student in Heidelberg, he studied translations and commentaries from figures like the German philosopher Leopold Ziegler (1881–1958). The early philologists whose work Fromm read named a “Pali Canon” that they perceived to be akin to the Christian Bible, arguing that it represented the “original” teachings of the Buddha and thus the essence of Buddhism. Fromm signals the fact that such textual study diverges widely from the lived experience of the vast majority of peoples that we call Buddhist when he refers to an “early Buddhism” contrasted with later, “popular” traditions that had purportedly strayed from these origins. This “early Buddhism” was introduced to Anglo-European readers like Fromm as an atheistic, rational, and—importantly—uniquely psychological religion of the mind.

By the 1940s, like many others of his generation, Fromm had discovered the work of D. T. Suzuki (1870–1966), the leading modern(ist) Zen Buddhist proponent of his day. Since the turn of the 20th century, Suzuki had worked for the cause of his mentor, Soyen Shaku Roshi, to promote a Zen Buddhist tradition in the United States and Europe that was based on direct experience rather than faith, an approach they argued was compatible with the advancements of modern science and philosophy.

In his writings, Suzuki introduced a Zen that uplifted the individual and advocated that practitioners challenge their preconceptions. All this undoubtedly appealed to Fromm. Although the organizational structures of Chan/ Zen/Son Buddhist communities have historically been extremely hierarchical, Fromm came to believe that even the Zen teacher/student relationship was fundamentally “anti-authoritarian.”

Suzuki, meanwhile, believed that the fields of psychology and psychotherapy would be fertile ground for this effort. He subsequently wrote to one of the most prominent psychological figures of that time, the analytical psychologist C. G. Jung, to request that Jung pen a new foreword to the 1939 German translation of his Introduction to Zen Buddhism (first published in Japan in 1934). Jung agreed.

Suzuki started lecturing at Columbia University in 1952, and psychoanalysts who listened to his talks began to think that Zen Buddhist teachings might hold new ways of generating transformative states of insight that they considered essential for psychological healing. Fromm wondered if the sudden enlightenment (satori) that Suzuki described could be a form of this fundamental therapeutic goal, and he sent the Zen teacher two of his own books, hoping to convince him that they were working toward similar ends.

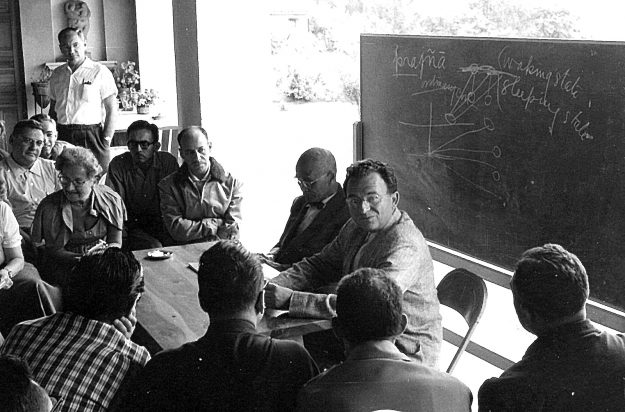

Their correspondence eventually became a friendship, which led to a watershed moment in the investigation of Buddhist traditions by US psychotherapists: a 1957 conference in Mexico at which Fromm and Suzuki met with some fifty psychoanalysts. Out of the conference came the 1960 book Zen Buddhism and Psychoanalysis, with papers from Fromm and Suzuki, including a series of comparative analyses between Buddhist and psychoanalytic concepts.

Fromm became a vocal critic of religious practices marketed as a “means of feeling better . . . without a basic change in character.”

Many of the points they highlighted often resurface in discussions today: For example, therapists continue to draw parallels between the Buddhist teacher/student and the analyst/analysand relationship, a comparison that Fromm made in the book. He wrote that “the analyst, in years of common work with the patient, transcends indeed the conventional role of the doctor; he becomes a teacher, a model, perhaps a master” comparable to the Zen master. Fromm ultimately suggested that analysts could not only learn from Buddhist teachings but also help Zen students by “avoiding the danger of a false enlightenment (which is, of course, no enlightenment) [by helping] the Zen student to avoid illusions.”

Zen Buddhism and Psychoanalysis would go on to sell more than a million copies, as the American fascination with Zen grew; new zendos [meditation halls] were established increasingly by individuals of European descent, and references to Zen Buddhism suffused the pop cultural milieu.

Fromm can be seen as playing a role then in a popularization of Zen that was at times crass, and this experience may have been part of what made Fromm’s own enthusiasm wane later in his life.

In his essay for Zen Buddhism and Psychoanalysis, he stressed that “all of this is not a ‘technique’ which can be isolated from the premise of Buddhist thinking, of the behavior and ethical values which are embodied in the master and in the atmosphere of the monastery.” By the 1960s, Fromm had watched Americans take up one Asian religious practice after the next, from yoga to tai chi to Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s Transcendental Meditation. In writings later collected in The Art of Being (1993), Fromm expressed concern that even his therapist colleagues could at times fall into “mixing up legitimate methods . . . with cheap methods in which sensitivity, joy, insight, self-knowledge, greater effectiveness, and relaxation were promised in short courses, in a kind of spiritual smorgasbord.”

Fromm became a vocal critic of what he dubbed the “mass production of spiritual goods;” religious practices marketed as “means of feeling better and of becoming better adjusted to society without a basic change in character.” He repeatedly warned against merely “adjusting” people to the oppressive forces of modern-day society without achieving this more foundational “change in character.” Fromm’s view was that psychoanalysts’ true aim in this regard was to release their patients from the intrapsychic structures that would incline them to submit to those forces, thus allowing them to instead take action toward social change.

Fromm could be writing these words today. One regularly reads critiques of our current equivalent of the 1950s Zen boom, the so-called mindfulness movement, as merely inuring people to the unjust conditions they otherwise might resist. These commentaries are presented as new insights, but Fromm and others had already expressed such concerns many decades ago.

Later in his life, Fromm came to believe that, rather than Suzuki’s Zen, a practice we would recognize as mindfulness meditation could be an antidote to this situation. He had learned this practice from Nyanaponika Thera (1902–1994), a Theravada monk whose book The Heart of Buddhist Meditation (1962), based on his training in vipassana meditation with Mahasi Sayadaw, is a seminal text for the mindfulness movement. Nyanaponika introduced the idea that a specific meditation could “provid[e] the foundation and the framework of a living dhamma [dharma] for all” that was highly applicable to “the modern problems and conditions” of contemporary life.

Fromm and Nyanaponika had much in common. The latter, once known as Siegmund Feniger, was also born Jewish in Germany and had survived the Nazis. Nyanaponika first took up Buddhist practice in his early twenties and fled to Sri Lanka, where he received ordination in 1936 at a monastery established for European expatriate Buddhists. Having escaped the Nazis, he then spent the war imprisoned in an internment camp by the British colonial authorities, who were wary of suspected German spies. Fromm and Nyanaponika were introduced in the early 1970s, and Fromm began a daily practice in the meditation style Nyanaponika had taught him. It was this practice that Fromm believed could generate the “character change” he saw as critical to human liberation.

In some of his later writings, Fromm concluded that there was a “difference between the Buddhist aim of total or partial enlightenment and Zen satori.”

Fromm did not pursue knowledge for its own sake but sought wisdom that could benefit humanity and alleviate the pain he witnessed.

Here he defines satori as “a sudden experience which breaks the perceptions of concepts and ideas,” an experience that might just as easily “be achieved in a similar way by some drugs.” Thus, while an authentic “Buddhist aim is change of character achieved by insight and constant practice, Zen Buddhism does not essentially aim at character change.” In Fromm’s view, the meditation practice he had learned from Nyanaponika was a pure, original form (he referred to it simply as “Buddhist meditation”) in contrast to a later developed “Zen.” To Fromm, it was a singular meditation practice that, like psychoanalysis, could bring the total psychic transformation necessary for individuals to achieve their full potential and work against the systemic oppression of totalitarian regimes and unjust economic systems.

The Fromm biographer Lawrence Friedman has written that Fromm “often spoke in prophetic language.” Indeed, Fromm can be viewed as prophetic as both an “early adopter” of contemporary mindfulness practices and an outspoken advocate of using such practices for more than “relaxation.” Whether or not they are responding to Fromm’s prophetic call, there are communities of both psychotherapists and Buddhists who continue to contemplate some of the same questions that Fromm confronted throughout his life. Listening to contemporary debates—or even, as religious studies scholar Ann Gleig has called them, “mindfulness wars”—it can sometimes seem as if we imagine we are the first to struggle with what constitutes true liberation. By looking back at the history of figures like Fromm, today’s practitioners may be spared having to reinvent the wheel, if not “dharma wheel,” and gain greater illumination for their paths toward enlightenment.

Fromm maintained a posture of openness and curiosity that is worth emulating. He was constantly searching for new ideas, even when those ideas challenged prevailing opinion or his own assumptions. He did not pursue knowledge for knowledge’s sake alone but sought wisdom that could benefit humanity and alleviate the pain and suffering he witnessed. Fromm’s very person speaks to some of the pressing issues of our time. Even as he coped with his own trauma as a refugee fleeing Nazi Germany, Fromm dedicated his life to finding methods to heal others from the suffering caused by social inequities and systemic injustice—a healing that he believed authentic Buddhist and psychotherapeutic traditions were both truly meant to provide.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.