The award-winning poet and conservationist W.S. Merwin died in his sleep on Friday, March 15, 2019 at his home in Hawaii. He was 91. Merwin’s many honors included the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, the National Book Award for Poetry, and being named the US poet laureate. The executive director of the nonprofit Merwin Conservancy, Sonnet Coggins, told the Honolulu Star-Advertiser that he died peacefully in his sleep. “That was what he wanted, to be in his home,” she said.

“Many lives ago I stood where you are standing,” writes W. S. Merwin in his poem “Fox Sleep,” “and they assembled in front of me and I spoke to them/ about waking until one day one of them asked me/ When someone has wakened to what is really there/ is that person free of the chain of consequences/ and I answered Yes and with that I turned into a fox.” The poem paraphrases Case 2 of the koan collection The Gateless Barrier, a case called “Pai-chang and the Fox.” The koan deals with the nature of liberated activity within the realm of cause and effect, and it is one of the most widely commented-upon koans in Zen literature. But you won’t likely hear the new U.S. Poet Laureate talking about it.

While Merwin is known to have studied with Robert Aitken Roshi in his adopted state of Hawaii, and has spoken a bit about Buddhism publicly (for instance, on PBS), he made it clear when we spoke this summer, that—as the famous narrator of Melville’s “Bartleby the Scrivener” continuously insisted—he “would prefer not to.” When I mentioned The Gateless Barrier’s appearance in “Fox Sleep,” he said, “That’s pretty rare, because I try to keep [direct] references out of the poems. But that was all there because of the fox.”

But to say that Zen infuses his poetry would be an understatement. Even before Merwin took up formal Zen training, he seems to have evinced an affinity for its meditation practice, which is, after all, based on unifying the mind, body, and breath. As Ian Tromp writes in the Times Literary Supplement, “Another [Merwin] poem names and demonstrates the principle at the center of Merwin’s poetics, speaking of the ‘furrow/turning at the end of the field/and the verse turning with its breath.’ Since 1963, Merwin’s poems have relied on the breath as their fundamental measure, and his work is best read aloud.”

So why is he reluctant to discuss this central aspect of his work? Perhaps his reticence relates to what Merwin told me about Jorge Luis Borges, the renowned Argentine poet and short story writer: “I remember Borges giving a series of talks. And they’re all very very interesting. The one on Buddhism is a little silly. There’s a whole lot he didn’t understand. But there’s a whole lot nobody really understands [about it].”

But, of course, when Zen people talk about not understanding something, it can mean what we normally mean; or it can mean something else entirely. In Case 20 of the Book of Serenity, one finds the key phrase “not knowing is most intimate,” “intimate” here being roughly synonymous with “awakened.” This calls to mind Shunryu Suzuki’s famous observation in the Western dharma classic Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind: “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s mind there are few.” So is it possible Merwin was indeed talking about Zen (“there’s a whole lot nobody really understands”), despite his intention not to? Sure.

In “A Letter to Su T’ung Po” (2007) Merwin brings alive something of the blend of openness, responsiveness, and resonance with the world that is the mind of not knowing: “Almost a thousand years later/ I am asking the same questions … / I do not know any more now/ than you did then about what you/ were asking as I sit at night/ above the hushed valley thinking/ of you on your river that one/ bright sheet of moonlight in the dream/ of the water birds and I hear/ the silence after your questions/ how old are the questions tonight.”

I’ve heard it said that in its intellectual content, Zen neither has nor is a philosophy, but rather it is a literary tradition. Merwin, for obvious reasons, seems drawn to this aspect of Zen, and while general questions about Buddhism and his own practice did not interest him, the literary tradition was a different story. He is a writer with a huge range of literary influences, and in talking about his work, just as in the work itself, he can’t help but converse with and about the various streams of influence.

Merwin has won the Pulitzer Prize twice (most recently for The Shadow of Sirius), along with nearly every prize an American poet can win (Yale Younger Poets prize, the Tanning Prize, the Lenore Marshall, the Ruth Lilly, the National Book Award). He has written more than forty books of poetry and prose, and he has done translations from a great number of languages (he is quick to point out that he does not speak them all). His work is often political, yet by never compromising on aesthetics, he has helped firmly link the peace and environmental movements with American letters.

In “Avoiding News by the River,” an early poem, Merwin writes, “I am not ashamed of the wren’s murders/ nor the badger’s dinners/ … If I were not human I would not be ashamed of anything.” This Poet Laureate has identified himself for decades as stridently antiwar, anti-pollution, indeed anti-hurry, anti-acceleration—almost anti-worldly or anti-modern. But Merwin’s earlier indignation has mellowed and turned inward and speculative in his later work.

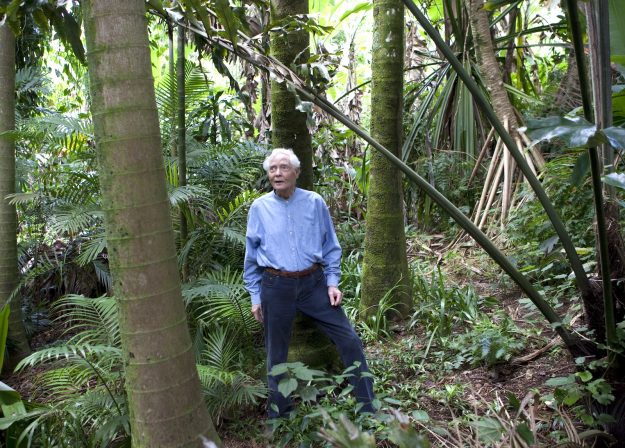

Traveling to visit him, I saw that almost everywhere you look, from the state’s license plates to its daily sun shower– drenched skies, you see Hawaiian rainbows. His major nonpoetry project is the Merwin Conservancy, some eighteen acres of rainforest he has assiduously restored from a pineapple-farmed wasteland. For three decades Merwin has toiled in this “garden” that preserves endangered plant species—mostly palms, including the local Pritchardia varieties.

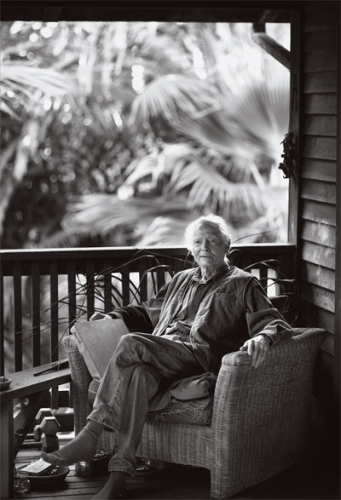

The day we meet, a Tuesday in August, we sit on an open-air veranda overlooking acres of palms. A Hawaiian thrush, the ‘oma’o, sings to us. From the moment I shake Merwin’s hand, I sense an only slightly distracted warmth, poetic keenness radiating from his eyes. Warmth that is, as poet Elizabeth Bishop described a sandpiper: finical. His wife, Paula, serves us a lunch of fresh pasta with basil and, later, mangoes. She chimes in affably (his masterpiece is The Folding Cliffs, she suggests, in response to my favoring The Lice). Looking out at his palms, he lets slip an encyclopedic storehouse of literary biography and memorized verse. Relentless from the outset, the mosquitoes are now only somewhat held at bay by a burning dab of punk. I swat; Merwin is composed.

In describing his life, his literary influences, he remains—this is again the word—composed. But in discussing his interests, he can also relate very naturally, legacy for legacy, to a 13th-century Japanese Zen master and poet, Muso Soseki, whom he translated and who he says fascinated him. This and remembering first reading the Diamond Sutra seem to animate him more than anything else we discuss. He admires Soseki’s sensibility toward gardening above all, not to mention his swordsmanship—a swordsmanship, as it were, without a sword.

Your dad was a minister? A Presbyterian minister.

I’m wondering if his sense of the sacred text influenced you in becoming a poet? I think so. And I’m grateful for that. We had to go to church and Sunday school even as small children. I was allowed to draw pictures during the sermon. I listened to the language of the hymns and kept asking my mother, “Now, why do they say it thatway?” One hymn [by Joseph Addison began] “The spacious firmament on high…” I didn’t know what the words meant. I was four. But I was fascinated with them. I knew a lot of the King James Version of the Bible from my father’s reading—just by heart, without even thinking about it. That was a different kind of English that rang in my ear. And I was very fond of it. And my mother read poetry to us. I think this is of huge importance to children, not just because of literature, but because that makes a connection with your parent, as a voice, the sound of it; through that, the whole current of that voice coming from other generations. I mean, it links you with something.

Your ancestors, the way they thought, spoke. Yeah, and the ancestors of the poems too. Because there were always words in the poems that you wouldn’t use. Maybe not all children would be, but I was immediately grabbed by it. I was grabbed by every kind of language. And the fact that words had these other dimensions to them, you know, that you find out about. I just began to pay attention.

Do you remember the first poem your mother read you that you loved? There was one Tennyson poem, “The Brook.” It starts with words I didn’t understand at all: “I come from haunts of coot and hern…” I thought, what’s a coot, what’s a hern? “I chatter, chatter as I flow/ To join the brimming river,/ … men may come and men may go,/ but I go on forever.” It gave me gooseflesh even as a small child. And we read Robert Louis Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses. There’s still one of the poems out of that collection that I think is a major poem in English: “Where Go the Boats?” Do you know that one? “Dark brown is the river,/ Golden is the sand./ It flows along forever,/ with trees on either hand.” There’s that linked thing of streams and water in those poems that I remember, and that probably says something, if we want to get Freudian about it. I certainly don’t.

One writer who always points back to Stevenson is Borges. He loved Stevenson, and I revere Stevenson. I think he’s a marvelous man. And he spent quite a long time in Hawaii, on the way out to Samoa—and played cards with King Kalakaua, and a beautiful princess, who was, I think, 14 at the time. She married and went to England and died of TB. Very beautiful. And there are wonderful stories about it that Stevenson told. Kalakaua cheated at cards, you know. They obviously got along very well together, Stevenson and Kalakaua. They were playing cards one day, and Stevenson said, “I’ll beat him this time: four aces.” And Kalakaua said, “Five kings beats it all.” [Laughs.]

Sounds like you enjoy reading biographies. I just finished Peter Ackroyd’s on Blake. Isn’t that a wonderful biography? [How he was] writing in his brother’s notebooks all the time. But the funny thing, the strangest thing to me about Blake, was that in some ways he thought he hated nature. But he’s got nature embedded in every word he writes, and he’s not aware of that. He’s a sort of urban kid. I think he was ill at ease outside London. But I hate even using the word “nature,” because it assumes that we’re not part of nature. We’renature, the same way the thrush there is. Or the leaves. It’s all one. It’s all natural. Even our artificial things—our artifice is, in a way, natural. I’ve always felt that since I was young.

The historian William Cronon writes about this sense shared by many of the Romantics that we “aren’t nature.” He writes that this underlies our creation of national parks as a space almost quarantined off from civilization, in a false dichotomy. One of the things that happened just before industrialism, I mean it was already there, was this anxiety creeping in about the connection with nature. Up until then, the natural world is taken for granted, even in spite of Christianity and Hebraism and all of that, the Book of Genesis, the Western assumption—which I think is deadly. There’s this idea that comes up—and is reinforced in the Renaissance—of the animism underlying mythology, with the nymphs and dryads and all that. I mean, they overbeat the drum until it was corny, but that’s what it was. You were not separate from it. They understood that. Shakespeare certainly understood it. Look at As You Like It. And you know, a figure like Prospero, inThe Tempest, is a sort of summary of all that. The magic is all there. It’s not something spooky that is supernatural. It’s natural.

I’m just thinking about the relationship between this spot, Peahi, in Maui, and the poems. I was trying to refresh my memory and track when one sees Hawaii appear as the predominant landscape in one of your books. Wasn’t it Opening the Hand, in 1983? I think it was The Rain in the Trees.

But there’s a great pineapple plantation poem in Opening the Hand, where the narrator is critical of the tourist for seeing without absorbing the culture. Is that in Opening the Hand? I think it is. But there’s a lot of the Hawaiian landscape in The Rain in the Trees.

Well, backing up into another landscape, I have to say that The Lice seems like the culmination of a lot of amazing leaps. Everything since then has been extraordinary. It seems as though in The Moving Target, just prior to The Lice, there was some amazing growth. And then in The Lice it all seems to gel. Poem after poem seems utterly original and masterful. What landscape is that? Europe? France? A few landscapes? Yes, and the city is all New York.

It doesn’t seem like the landscape is explicitly named. But there does seem to be a specific landscape there, behind the poems. A lot of it is that village in southern France, and that whole area. One of the great draws of that place—the thing that made me love it from the beginning—was the feeling that I had walked, as if in a fairy tale, into a place that had an unbroken connection with a deep past, that everybody simply took for granted.

That’s usually a surprise to an American, I suppose. Yes. My mother had no family because she was an orphan. And she didn’t like to talk about her past, because there was so much death in it. And my father’s family just had obliterated the past, just didn’t want to know about it. If they thought about it, they were a little ashamed. My grandfather was ruled out because he drank. So there was only this cousin of my father’s who looked after us when we were children—who was virtually illiterate. She was kind of suspicious of me for being interested in [the past]. She realized she was a little strange. But I would ask her questions, and she would tell me what she knew. She’d say, or want to say, “Billy, why do you want to know these things?”

But your life in southern France contrasted with that. Yes, and I could come back having been halfway around the world and nobody would ask a single question.

Where were you when you wrote, “When You Go Away”? In France.

That one seems to encapsulate a lot of what you were learning as a poet very beautifully, in particular how to write about the abstract, grief, loss, absence. There’s that especially evocative image, “It is the time when the beards of the dead get their growth.” Did that poem come quickly? It’s not autobiography or anything. A couple of friends who died— that was part of it. But also, I realize the first modern poet I read was not in English at all; it was Lorca. I took Spanish in college, and there was a young professor there who wore a beret and rode a bicycle everywhere and was obviously terribly homesick for Spain. And he asked me and a couple of other students to help him translate the plays of Lorca. Which I helped him do. And in the course of it I started reading Lorca’s poems. The poems interested me far more than the plays. And I read Neruda very early, too, Residencia en la tierra. And Juan Ramón Jiménez. Those were the three. I loved reading them. They seemed very foreign to everything that was happening in English, and I didn’t quite know how to digest them. But I went on reading, taking great pleasure in them. And it wasn’t until years later, after I read them at the university, when I was in my very late twenties and I sort of stopped writing, I came to the end of The Drunk in the Furnace. And I said, “That’s OK. But I don’t want to go on writing that way. It gets repetitive after a while. I’ve got to stop writing. And if I write again, it’ll be quite different.” I stopped for quite a few months, which I’d never done before. And then all the early poems inThe Moving Target I wrote in about six weeks.

The Spanish and Latin American writers helped you evolve your style then? Neruda above all. And I don’t think they are imitations of Neruda. But Neruda was a very sort of freeing voice.

How did you come upon Muso Soseki’s work? That was after I was living here. Soiku Shigematsu was the guy I translated Soseki with, because I don’t know Japanese. His father was a Rinzai Zen priest. I went to Japan and visited him a couple of times. He came here to see Robert Aitken. We got to know each other when he was out here—I think it was Aitken who introduced us. He wanted to know if we could work together. I said, “Let’s try.” I was fascinated by Muso. It’s a side of the life of Kyoto at that time, because it’s not one of the mainstreams of Buddhist teaching. It was for a while, but it isn’t anymore. He was a very interesting temperament. He was also a master of Kendo, swordsmanship—and a very high aspect of it where you didn’t use the sword at all. He trained a man who became the best swordsman in Japan. And they were crossing on a boat at one point and there [weren’t enough] seats, and a man sort of pushed Muso aside and sat down in the chair, and the swordsman was furious. And as soon as they got out of the boat the swordsman went to this man and challenged him and started to draw his sword, and Muso said to him, “You don’t understand anything.”

The title of your translation of Muso’s poems is Sun at Midnight. What does that refer to? Muso’s title [of his book of prose] was “Dialogues in a Dream,” and at the very end, Takauji, the emperor who had given up the empire to his brother because his conscience was so troubled by the civil war that they had both fought and that they had won—he just couldn’t bear it. He had these 99 questions for Muso. Muso’s book is the answer to those questions. And in the last question, he says, “What is the final truth?” And Muso said, “The sun shines at midnight.”

I understand Muso, like you, was quite a gardener. Yes. One of the questions that the emperor asks him is: “You are very interested in gardens. Is not gardening just another form of being attached and acquisitive?” And Muso gives this extraordinary answer about attitudes toward gardening. He says, “Yes, it can be that. [For] those who want to show off with this or that…” But then he says, “Lo-t’ien had one little pool and one bamboo plant, and he cultivated them with great love. He cultivated the bamboo and kept the pool clear, and he wrote a poem. He said, ‘The bamboo—its heart is empty. It will be my friend. The water—its heart is pure. It will be my teacher.’” And [Muso] said, “Those who for the space of the morning love the rivers and mountains in this particular way have the spirit of Lo- t’ien.” And he said, “So you see, gardens like everything else in life can be a form of selfishness and acquisitiveness. Or they can be a source of reality.” It’s a beautiful passage. And he doesn’t put it in time. He says, “Those who for the space the morning can love the rivers and mountains.”

In addition to Muso Soseki, what other great Zen literature has inspired you? I am extremely chary about talking about it and feel that much too much has been said about it already. I don’t think of this as some dazzling discovery that completely changed my life. I think that finding certain writings of Zen, or of Buddhism, seemed to confirm something that I had been reading toward for years. I mean, there was a whole background in how mysticism from both East and West—I mean Eckhardt and Plotinus and Spinoza—these people were, and they remain extremely important to me. I’m certainly not a Christian and I have nothing to do with Christianity. I mean, I don’t oppose it, but I don’t go that way at all. To me there’s something that just doesn’t work in the whole idea of monotheism. The first Buddhist text that ever caught my attention (this was when I was back in my early thirties) was the Diamond Sutra. The Diamond Sutra is still very important. And to me Taoism was every bit as important as Buddhism, and it remains so. So it’s complicated. But the Diamond Sutra was the first of them, way back in my thirties, and then Dogen. And Dogen’s successor Keizan Jokin. Those are the three major ones for me.

Take them away, names like Buddhism. I’m impatient with them. There’s something beyond all that, beneath all that that, they all share, that they all come from. They are branches from a single root.

You wrote an introduction, I understand, to a book of Dogen’s work? What happened was, [I agreed] to collaborate on some translations of Dogen’s poems. I’m just grateful to Dogen for his writing, first of all, and for his example—which is not the way I want to live, but which is his way of looking at the world. And it’s very related, you may say, to that kind of awareness, to what I like to keep bringing up in the thing to do with the laureateship. One of the reasons I took it this time was to be able to say something about the relation between the imagination and the environment. I don’t think there is a separation. I don’t think we have an imagination apart from the environment, either. And I don’t think we have an existence apart from the environment either. And if the imagination isn’t about our existence, I don’t know what it’s about. It’s not about making money, that’s for sure.

What aspect of Dogen’s example are you grateful for? The way he takes a subject and doesn’t look for a rational answer to it. He examines it from all sides and plays light on it. He’s really writing poetry all the time. If you’re looking for neat formulaic answers in Dogen, you don’t find them. You don’t find them in Keizan, either. Those are the guys who can— you have to come at them from a different part of your own mind. That’s the part of Zen practice to me that’s attractive. But it’s not unique to Zen. It’s there in Taoism. It probably was there in parts of the practice that became Greek Orthodoxy, that came out of the desert. The origins of all of those things are extremely ancient; they’re older than what we think of as the beginnings of Buddhism. The origin of Taoism may be completely on its own. But all of them go back to shamanism. And we don’t know the history of shamanism; it’s all speculation. They link in my mind to things which are incredibly ancient.

The paintings in the Paleolithic caves? Those aren’t art; they weren’t there for an audience. Except the great halls, which were initiation places. But the tiny figures that were 25 feet up inside a cleft where nobody could ever see them, an animal that someone built in there? Those animals are part of the person who put them there. And that person came down knowing something, and this is the ultimate vision quest. And it didn’t even begin with Cro-Magnon man. We found five years ago in Southwest France a place quite near Lascaux with a history of its own that has never been published because the scientist who discovered them—the government of France would not let him go on with his own excavations. So he said, OK, well, I won’t publish my findings, then. And he hasn’t. He’s kept them going for years, and I talk to him on the telephone. What he found sixty feet down was a burial. It was not Cro-Magnon. It was Neanderthal. It was probably, he thinks, 19,000 years older than Lascaux. [It] was a complete Neanderthal skeleton and beside it the skeleton of a bear. And the bear’s legs and the man’s legs were exchanged so that the man had bears’ legs and the bear had man’s legs. And they were surrounded by fossil pollen. It was a ritual burial. That’s a great scoop, and it hasn’t even been published yet. But the reason I’m telling you this, is that this is already saying that the link between the imagination—which to me is the great pinnacle of humanity, the imagination that makes the arts and makes compassion—is ancient in our species and goes way back. And it’s never been separate. And when you get any aspect of the culture that tries to separate it, it’s destructive and suicidal.

Take them away, names like Buddhism. I’m impatient with them. There’s something beyond all that, beneath all that that, they all share, that they all come from. They are branches from a single root. And that’s what one has to pay attention to. And of course the actual words in the Diamond Sutra that grabbed me were, when Tathagata [the Buddha] says, “Bodhi, does the Tathagata have a teaching to teach?” And Bodhi says, “No, Lord, Tathagata has no teaching to teach.” At that point I got chills right down my spine. And Tathagata says, “Because there is no teaching to teach, it is the teaching.” I thought this is it, you know. Here we go. I think that goes as far back as shamanism. I mean, what did those guys find up in those clefts? in the caves? There was no teaching to teach. They knew something, but they knew it from then on. And it was something distinct, and it was something to do with connection, with following, with what came before and after, and they couldn’t express it in any other terms. But they were obviously guides to their people after that. Because you know, the animals that they were depicting were not the animals. I mean, they may have eaten a few of them. But that was not what it was about. It was about following, it was about the fact that these were the elders. They knew where they were going. The humans did not know where they were going.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.