Half-asleep in my hospital bed, I hear the voice of my partner, Martha, from the cell phone resting on my pillow. The words, so often recited in Buddhist centers, are familiar: “I am of the nature to grow old,” “I am of the nature to have ill-health,” the first two of the five remembrances. They bring me back to my body.

After many hours in the emergency room, I have finally arrived on the ninth floor of Kaiser Permanente Oakland Medical Center, a dreaded destination in the moment when COVID-19 is overwhelming California’s health care system. Already in my life I have twice come close to death, and in each instance I was given the gift of more time. Will that happen again? My life could have ended at age 59 with third-stage cancer. But after major surgery and many weeks of chemotherapy, I recovered. For the next 15 years I inhabited my extra time joyfully and energetically and expected that life would continue in this way. My body had its own agenda, however. Ten years ago, another medical emergency—caused by scar tissue from the cancer surgery—struck, to situate me once again in that territory between living and dying. This second operation was extensive and ultimately successful. Although the recovery period was long, I slowly realized that I could be strong and happy once again.

Now I find myself back in a hospital bed, wracked by the familiar gut pain, the result of an as yet undiagnosed intestinal obstruction.

The doctors have quarantined me in a room where I will spend the next seven days surrounded by hanging implements and computer screens, a good place for the hospital workers to begin a series of tests. Settled here in my bubble, lolling between sleep and waking, I hear activity outside my door, but I have no idea what the area out there might look like. My world has shrunk to the dimensions of this room.

This first night, in the wee hours, two members of the surgical team appear, to my delirious mind seeming like genies materializing from thin air. Of their young, masked faces, I see only concerned eyes. They have the results of the X-ray—or CAT scan, or whatever other diagnostic exam they’d administered—and in my grogginess I struggle to pay attention to their reports. Then the nurses join us, and the surgeons observe while the nurses insert a nasogastric tube through my nose and into my stomach, in an excruciating downward probe that feels as if it shreds the tissues of my throat. “We’re doing all these things to see if we can solve the problem without resorting to surgery,” one surgeon explains to me. I am to have no food or drink; the tube will drain the corrosive acids from my stomach up into a bottle. In this way my stomach and intestines can “relax,” the surgeon tells me, and they hope that the gut will allow this obstruction to move or break up.

How is it that I can feel so alone when I am surrounded by nurses and techs? The answer is blunt and simple. No family members or companions are being allowed into the hospital because of coronavirus restrictions. I remember other hospital stays when I took for granted that someone would be with me—in person, not just by phone. Now in Room 905, I realize what confidence and comfort are offered by a loved person’s being near. Without this, I feel forlorn, like a castaway tossed up alone on a bleak stretch of beach.

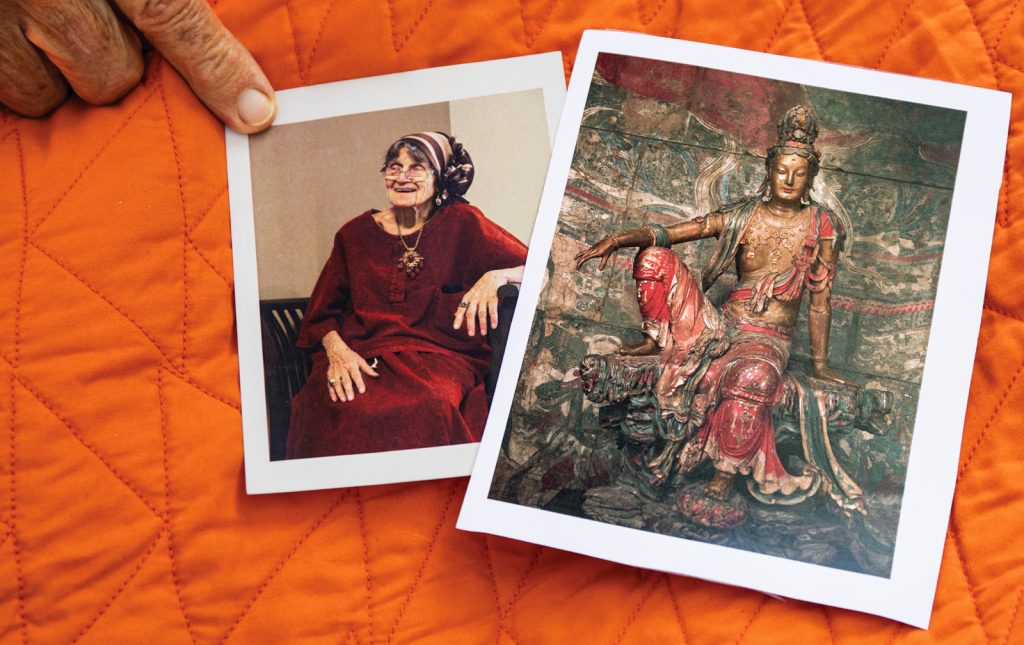

But on my bed table, I see the blue cloth bag that my partner has sent up to me from the emergency room. As usual, she had known exactly what I would need: two issues of the New Yorker, a book by Rosie O’Donnell given to me as a freebie outside the library, a pen, and a notebook, out of which fall two photographs. One shows a richly colorful ancient sculpture of an Asian woman sitting with one knee up and one arm balanced on it. This is the bodhisattva of compassion, Kwan Yin, in the powerful posture known as “royal ease.” The other depicts Ruth Denison, my Buddhist teacher. She looks very old and utterly delighted, and I recall her voice speaking to her students about the eventualities of old age, sickness, and death.

“You’ll see,” she would tease us, “this will happen to you, too.”

Kwan Yin looks out at me from half-closed eyes, resting, as usual, in the midst of chaos, in a strong, still attitude.

It’s December, and we are in the midst of a surge of new coronavirus cases in California, filling all the beds in this giant hospital. A tech tells me that COVID patients are being situated down the hall from my room, and I remember the relentless news footage of desperately ill people, some attached to ventilators, unconscious on their bellies as teams of doctors and nurses labor to keep them alive. I feel in my own body the pain of this, and I react: It’s not fair! It’s against the natural unfolding of our lives to sicken this way! This can’t be the proper fate of these people! Then Ruth Denison’s rich voice quotes the remembrances, reminding me, “I am of the nature to fall ill; there is no way to escape from ill-health.” Heeding her words, I try to find the energy to practice tonglen—breathing in the suffering of all sentient beings, breathing out ease, tranquility, and tender caring. Tonglen, when practiced wholeheartedly, transforms painful feelings into light and spaciousness through the depth of one’s being. But I find myself too weak in my present condition to manage this. I can only simply be here.

F

our days into my hospital stay, the surgeon, Dr. M, tells me that the measures they have tried, hoping to alleviate my problem, have not been successful. It is clear now that a blockage exists in my small intestine, preventing the passage of any contents. “We’re sure this isn’t a recurrence of the cancer,” she says, “but you are in a dangerous situation and we’re recommending surgery—now.”

Dr. M and I have locked eyes above our masks. I see her intense desire that I understand.

“If you choose to have surgery,” she continues, “we’ll make a small incision in your abdomen and insert a tiny camera to look closely and identify the blockage and clear it.” She pauses and I see the shallow flutter of her mask as she takes a breath. “If that is not possible, we’ll have to make a larger incision, like the ones from your previous surgeries, to open up your belly and work on the obstruction, whether that is a tumor or some other cause.”

She steps back an inch. If I choose surgery, she explains, they might have to remove a portion of my intestine. The recovery would be long and difficult. Worst case, I would have to void my intestine into an external bag. I know people who live this way, and it is an inconvenience and discomfort that I would not want to choose.

Gazing into Dr. M’s steady eyes, I feel tears pushing up. I am so very sorry for myself and so very scared. I quell the tears, thinking they will just drag out our communication. But Dr. M, who has appeared so clinical and detached, sees my struggle and places a warm hand on my arm. Her touch is comforting; I feel a wave of gratitude.

“And what will happen,” I ask, “if I decide not to have the surgery?”

She tells me about the chronic pain and difficulty, the recurrence of the problem—all sounds grim—ending with the possibility that my intestine might rupture and kill me. Or, if I live, I might never be able to eat again.

She then tells me that the surgery, if I choose it, should happen today. “I’m going to leave you now, to give you some time to talk with your partner,” she continues. “I’ll be back in an hour. And if the answer is yes, we’ll immediately take you down to surgery.”

When she’s gone, I lie with the phone at my cheek. Finally the tears come, and I hear Martha crying, too. “I’ve done this before,” I remind her. “I will do it this time. But I don’t think I’ll ever do it again.” I know she does not want to hear this. I am 85 years old, and I know that yet another major surgery could leave me disabled, lost in dementia, or worse. Do I really need more time?

Ruth Denison’s voice reminds me, “I am of the nature to fall ill; there is no way to escape from ill-health.”

Eyes closed, I see the dark walls of a tunnel through which I am moving. I realize that at some point I will have to turn left or right, and that the left-hand tunnel leads to something deep and final. I bring to mind the few close friends with whom I would want to share my experience of surrender, and hold conversations in my head, just letting them know where I am and how I feel about it.

Later that day, I awake from a nap, and in a half-conscious state I see, propped on the blue bag, the photograph of Kwan Yin, sitting so erect in her beautiful red and gold trousers and robe, her eyes half-closed in compassionate attention, her presence a vivid embodiment of spiritual power. I bring her into the room with me, as I wonder, if I knew I were dying, whether she might spontaneously appear, splendid in her royal garments, to accompany me. Would I ask her to save me? Save me from what? No, I would want to know what she asks of me, and I would reflect on the ways in which I have been with her throughout my life: offering myself to her, learning and teaching her practices to other people, doing her work—writing two books about her. I wonder, has all this pleased her? Have I truly come closer to her through my efforts and studies?

In my future-vision I see us moving side by side, her radiance lighting the dark walls of the tunnel, the two of us earnestly speaking together as I realize she is letting me go. And I know it doesn’t matter, for it belongs to a different reality that will dissolve in succeeding moments. Then I hear a voice—the nurse telling me the orderly is here to take me to the operating room. So from my bubble I am wheeled out the doorway into the hall. And Kwan Yin slowly disappears.

After the surgery, I receive the news that there is no evidence of recurrence of cancer, and I find myself back in Room 905. Curled on my side, safely tucked in, I’m curious about what this body has just been through; I want to take a look and pull up my gown to see the long wound held together with staples, which march up my belly like a line of little soldiers. With each of my movements, their metal legs pull on my tender skin, and I wonder when I will feel the effect of the painkillers in the bag of fluid dripping into my arm.

I sleep and wake, sleep and wake, and by the second day I feel strong enough to want to move. A tech helps me hobble from the bed to a chair facing the window, bringing with us the hanging bags and the monitor connected to leads on my chest. She settles me, pulls the table close, and telegraphs a smile from kind eyes above her mask.

What a relief it is to sit up in a chair and look out the window at the larger vista of Oakland’s streets and storefronts. Rain caresses the glass, blurring the gray blocks of buildings along MacArthur Boulevard, softening the profiles of distant hills. I watch the rain, imagining what the tiny droplets would feel like touching my face.

The surgery has left me without defenses, without psychic protection. With my skin and heart and eyes I can feel the vibrations of air moving, I flinch at a careless or hurried movement, at voices sounding, metal scraping floor. I feel completely permeable and helpless, gradually realizing I inhabit a reality carved out in me by the huge invasion of surgery and anesthetic. Every tiniest event arrives with stunning clarity as I watch the nurses perform their roles, appreciating their skill and consistency, seeing them as if from a distance—space and silence separating us. I wonder if nurses guess the impact of their interactions with us. Is gentle caring taught in nursing school, in the tech training programs? Or is it just inherent in some people and missing in others?

As the anesthetic gradually leaves my body, I return to a more “normal” state of mind but still am relying on pain-killing drugs for the incision and staples. That night, a surgeon instructs the nurse to remove my nasogastric tube. Leaning close to me, she murmurs behind her mask that this will take only a moment, then she yanks the tube decisively—up, and out! The pain in its expected intensity is well worth it. I am free, and suddenly thrilled.

In the morning, I hear the nurses speaking of the difficult patient in 905. None of this do I remember, but apparently I had loudly complained, insisted that someone help me right now, and made rude comments to the nurse and tech and cleaning person, who all came to calm me down. How intriguing it is to have become the cranky patient, when I work hard in my life to maintain a mellow, calm demeanor, no matter what.

The drugs have unmoored me from my stable location in my identity, leaving me wondering how much of my personality—the stable, pleasant “Sandy”—is performance. I see this as more proof of the truth of the insubstantiality of the self. Anatta has arrived in my room.

A nurse named Ebiti comes in to give me a talking-to about my nighttime tantrum as she checks the monitors in my room. She reminds me of the pandemic, the crisis in health care that it is creating, and the suffering of the COVID patients whose families cannot be here to comfort them. “Tonight,” Ebiti instructs me, “watch the news programs to inform yourself about what’s going on.”

I feel properly reprimanded and instructed, offered a perspective larger than last night’s distress. Before she leaves, she adds “And you will get a walk later” as my reward.

In my continuing vulnerability, I am reminded of how relieving it is to enlarge one’s view, as Ebiti has done for me. I could get caught here once again in the pain of the staples pinching the margins of my wound, the discomfort and frustration of not being able to move freely, the pull of the needle in my arm. So instead, I open to my surroundings in this hospital ward and to the COVID patients.

I hear Ruth’s voice recite the third recollection, “All that is dear to me and everyone I love are of the nature to change. There is no way to escape being separated from them.”

The whole expanse of this ninth floor resonates to those words. And I ask my awareness to expand to hold this truth. I open out farther to the buildings of Oakland surrounding us. Seated at the window, I feel a rush of gratitude for the veil of raindrops that blurs my view of MacArthur Boulevard, the people in their cars or hurrying in the rain, everyone busily pursuing accomplishment or pleasure, love or just survival—the natural unfolding of life all around me, the more time that I can now lightly live.

♦

Thanks to Stephen Jenkinson for his exploration of “more time.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.