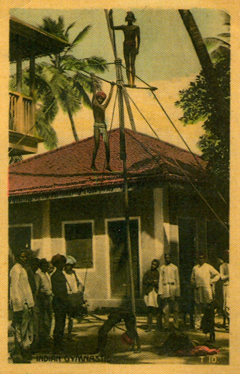

ONCE IN ANCIENT INDIA a bamboo acrobat set up his bamboo pole in the center of a village, climbed up the pole with great agility, and balanced carefully upon its tip. He then invited his young assistant to scamper up and stand on his shoulders, saying to her: “You look after my balance, my dear, and I’ll look after your balance. With us thus looking after one another and protecting one another, we’ll show off our craft, receive some payment, and safely climb down the bamboo pole.” “No, no, master; that will never do!” said the girl. “You must look after your own balance, and I will look after my balance. With each of us thus looking after ourselves and protecting ourselves, we’ll show off our craft, receive some payment, and safely climb down the bamboo pole.”

ONCE IN ANCIENT INDIA a bamboo acrobat set up his bamboo pole in the center of a village, climbed up the pole with great agility, and balanced carefully upon its tip. He then invited his young assistant to scamper up and stand on his shoulders, saying to her: “You look after my balance, my dear, and I’ll look after your balance. With us thus looking after one another and protecting one another, we’ll show off our craft, receive some payment, and safely climb down the bamboo pole.” “No, no, master; that will never do!” said the girl. “You must look after your own balance, and I will look after my balance. With each of us thus looking after ourselves and protecting ourselves, we’ll show off our craft, receive some payment, and safely climb down the bamboo pole.”

The Buddha tells this story in the Satipatthana-samyutta to illustrate the practice of mindfulness meditation, and the image of this perilous balancing act works on many levels to help understand what he was pointing to. The physical sense of balance is so immediate, so intimate, and so accessible in every moment of experience; it is often the first thing one gets in touch with when sitting down to meditate, and the story derives much of its strength from this fact. We are so used to projecting our attention out into the world around us, it is a noticeable shift when we face inward and feel the subtle swaying of the head on the shoulders, along with all the muscular microcompensations keeping our body centered in gravity. The acrobat, like the meditator, is bringing conscious awareness to a process that is always occurring but is generally overlooked, which is a vital first step to learning anything valuable about ourselves.

The story also vividly demonstrates why it is so important to attend to the quality of one’s own inner life before critiquing what others are doing. It’s just not possible to keep someone else’s balance, and it takes this graphic image to drive home such an obvious truth. Moreover, the acrobat’s assistant will only be able to maintain her own balance if the acrobat, upon whose shoulders she stands, is steady and reliable. In other words, the best way he can protect her from harm is to look inward and attend carefully to his own equilibrium. This is true of many things in life.

The analogy pertains to, for example, the impact a parent has on a child. As we all know, a parent can go on and on about what a child should or should not do, or say, or think, but nothing is going to influence a child’s developing personality more than the example actually set by the parent. Not until a mother or father keeps their own emotional and moral balance, will the child be able to learn how to steady herself upon their shoulders and understand their admonitions. The same applies to the doctor and patient, the teacher and student, the therapist and client, the politician and constituent, the author and reader—indeed to virtually every one of the relationships we form in our world. The quality of every relationship is enhanced by the care brought to it by each party, and this is especially important when one person depends directly upon and trusts the attentiveness of another.

Life itself is a balancing act. We are each of us perched upon a precarious pole, trying to stay centered in a swaying, breezy world. It is difficult enough staying safe ourselves, let alone trying to keep track of all the things stacked upon our shoulders. Mindfulness is a tool for looking inward, adjusting our balance, and staying focused on the still center point upon which everything else is poised. The quality of the present moment of awareness—that bamboo pole upon which we all hover—can be calm, stable, and focused, and when it is, our well-being and that of all those who depend upon us is well protected. When it is not, no amount of pointing to the doings of others can compensate or restore our balance.

One might misconstrue this teaching as selfish. But doing so would involve overlooking the subtle interdependence of self and other that the Buddha goes on to emphasize. The acrobat’s attention to his own equilibrium is motivated by his tender regard for the well-being of his beloved assistant. His initial suggestion that he will look after her balance is an expression of compassion, but it is not matched by an equal measure of wisdom. Just as a person mired in quicksand cannot help another until he has himself reached firm ground (to cite another analogy from the Pali texts), our ability to help others depends chiefly on keeping our own balance. As the flight attendants tell us each time we board a plane, one must don one’s own oxygen mask before helping others do so.

Looking after oneself, one looks after others.

Looking after others, one looks after oneself.

How does one look after others by looking after oneself?

By practicing mindfulness, developing it, and making it grow.

How does one look after oneself by looking after others?

By patience, non-harming, lovingkindness, and caring.

(Samyutta Nikaya 47.19)

Notice how the boundaries between self and other disappear. By showing kindness and taking care of others, one is being kind to oneself and is caring for oneself. Actually, helping others is the best way to attend to one’s own most basic welfare, just as harming others will invariably harm oneself. According to Buddhist thought, this is because all action, all karma, based as it is upon intention, effects not only the world “out there” but also one’s own dispositions and character. Everything we say and do and think shapes who we are, just as we go on to shape, through the quality of our awareness and the depth of our understanding, everything else in our world. In fact, as I understand this text, it may not be particularly useful—or even possible—to say where one leaves off and the other begins.

So what is the very best way to protect your child, care for your partner, contribute to your community, and express compassion for all the world? Look inward, carefully and often, and keep your balance. A lot depends upon it.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.