Change Your Mind Day 1997

Longtime practitioners, meditators-for-a-day, dharma bums, and dog walkers turned out for Tricycle’s fourth annual Change Your Mind Day on May 31. The afternoon of free, informal, introductory instruction is organized each year to introduce people of all backgrounds to meditation practice. For five hours, the Great Hill, a secluded and grassy slope at the north end of New York City’s Central Park, was transformed into a sea of cross-legged sitters and bare-chested sun worshippers drawn by the stillness. Despite overcast skies and predictions of rain, more than 1,200 people participated in this year’s activities, which included guided meditations from a variety of Buddhist traditions, contemplative movement, music, and a traditional Tibetan geshe debate.

Longtime practitioners, meditators-for-a-day, dharma bums, and dog walkers turned out for Tricycle’s fourth annual Change Your Mind Day on May 31. The afternoon of free, informal, introductory instruction is organized each year to introduce people of all backgrounds to meditation practice. For five hours, the Great Hill, a secluded and grassy slope at the north end of New York City’s Central Park, was transformed into a sea of cross-legged sitters and bare-chested sun worshippers drawn by the stillness. Despite overcast skies and predictions of rain, more than 1,200 people participated in this year’s activities, which included guided meditations from a variety of Buddhist traditions, contemplative movement, music, and a traditional Tibetan geshe debate.

As in years past, Tibetan practitioner Michele Laporte launched the day with 108 strikes on a massive, bowl-shaped gong. Pat Enkyo O’Hara of the Village Zendo and Laporte cohosted the event along with Tricycle’s Editor-in-Chief, Helen Tworkov. O’Hara led the first guided meditation and was followed by Acharya Judy Lief, a student of the late Trungpa Rinpoche and a teacher in the Shambhala community who led a meditation on the meaning of taking refuge. The New York Buddhist Temple’s Reverend T. Kenjitsu Nakagaki overcame a sore throat to chant prayers. Insight Meditation Society cofounder Joseph Goldstein gave the first of his two guided vipassana(mindfulness) meditations.

Rick Fields, editor of Yoga Journal and author of How the Swans Came to the Lake: A Narrative History of Buddhism, marked the halfway point of the day by reading some poems by his old friend, the late Allen Ginsberg, who had participated in past Change Your Mind Days. Then came the Tibetan geshe debate, always a crowd-pleaser, conducted by Michael Roach, an ordained monk in the Gelugpa lineage, abbot of the New York–based Diamond Abbey, and head of the Asian Classics Institute. Two monks debated each other in Tibetan on the meaning of nirvana. The fast-paced exchange, the hand-clapping, and the crowd’s roaring of approval or disapproval made it, once again, the most raucous event of the day.

Maggie Newman, a longtime teacher of T’ai Chi and Japanese dance, led a series of contemplative movements, and composer Jon Gibson performed two pieces on an instrument he fashioned out of PVC tubing, normally used for drainage pipes. The deep drone of the instrument resonated remarkably like that of a Tibetan long-horn.

The day drew to a close with a trio of teachings on the Buddhist principle of metta or loving-kindness. Khenpo Tsewang Gyatso, a Nyingma lineage teacher, led the first meditation.The Venerable Kurunegoda Piyatissa, Sri Lankan abbot of the Theravada New York Buddhist Vihara, discussed the crucial role of discipline in meditation practice. Gelek Rinpoche of the Jewel Heart Tibetan Centers (Ann Arbor and New York) gave a lively talk on the inevitability of suffering and the importance of developing compassion for ourselves. And as Michele Laporte closed the day with 108 gongs, the participants arrayed across the Great Hill sat silently.

Highway Death

On May 19, seven Thai monks driving from San Francisco to a temple in North Hollywood were killed when their van flipped over on the highway. Six of the dead, including the driver, were monks who had traveled from Thailand to celebrate the opening of a temple in Fremont, California. In Theravadan practice, monastics are not supposed to drive. Sangha members are questioning why a monk had taken the wheel.

Not in Our Back Yard

Residents of Yorba Linda, California, objecting to Asian architectural style and potential crowds, have quashed the efforts of the Myanmar Buddhist Society of America to build a monastery there. Members of the Society said they believed the city council, which rejected the building proposal, had tried to discredit their sangha. Residents near the proposed site tried to link the group to other Buddhist temples in southern California that have used meditation centers to host political gatherings, and to one temple that neighbors call an “eyesore.”

One resident, Jack Majors, objected to the size of the building and its proposed design, saying, “You have before you a project that compares to the Taj Mahal.” Another resident, Georgina Campbell, maintained that the architecture would draw crowds and cause traffic. Local clergy, meanwhile, defended the project. John Dalton, president of the Church of Latter Day Saints, who lives next to the proposed site, said he welcomed the Burmese Buddhists as “gentle people our children can look up to and learn from.” The only other building project to have been barred in recent years was a pool hall.

Doody’s Conviction Upheld

Jonathan Doody, who was convicted of killing nine people at a Buddhist temple near Phoenix in 1991, lost a Supreme Court appeal this June. Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz, who filed the appeal, argued that Doody, a Thai immigrant, did not understand his “Miranda rights” (the right tto remain silent or to have a lawyer’s help) when they were read to him. Doody was convicted in 1993 of murdering six monks and three other people at the temple. All the dead had been shot in the back of the head with a rifle. Doody’s own brother had studied at the temple.

The appeal said police had “downplayed the importance of the Miranda warnings” before beginning a twelve-hour investigation of the suspect. Noting Doody’s age (he was seventeen at the time) and the fact that English was not his first language, the appeal urged the court to use his case to determine whether the justice system “must use a higher standard in assessing the adequacy of Miranda warnings than might be the case where adults are involved.” But an Arizona appeals court upheld Doody’s conviction after ruling that an audiotape of the police warnings to him “supports the trial’s finding that Doody knowingly and intelligently waived his rights.”

Death Row Redux

On August 8, 1996, Frankie Parker, an Arkansas death row inmate and Buddhist, was executed for the murder of his parents-in-law (Tricycle, Fall 1996). Several years before his execution, while living on death row, Parker encountered a copy of the Dhammapada and began to study Buddhism. He ultimately accepted responsibility for his crimes and took refuge vows with Lama Tharchin Rinpoche and jukai, formal Zen refuge vows, with Eido Shimano Roshi.

Now, Parker’s best friend and fellow death row Buddhist, Gene Perry, has had his execution date set for August 6—nearly a year to the day after Parker was electrocuted. In 1980, Parker was involved in a jewelry store heist that left two people dead. Perry maintains his innocence in the murders, but admits to reselling some of the stolen jewelry. On May 28, he took refuge vows over the telephone with Tharchin Rinpoche. At press time, Perry was awaiting the outcome of a clemency hearing that could commute his sentence to life in prison.

Harrer Horror

On the eve of the premiere of Seven Years in Tibet, the film about Austrian Hans Harrer’s life in Tibet, the former tutor of the Dalai Lama is being dogged by his past as a member of the Nazi Party. The film, directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud and starring Brad Pitt, is based on Harrer’s best-selling book, which he wrote in the 1950s after fleeing Lhasa during the Chinese invasion.

According to documents obtained by the German magazine Stern, Harrer, who was a prominent mountaineer, joined the Nazi party in 1938 when Germany took control of Austria. He also joined the SS, the party’s police wing notoriously associated with the atrocities of the Holocaust. Harrer maintains that he joined the party in order to be able to further his teaching and mountaineering careers, and was interned in India by the British at the start of World War II. But the Stern documents also reveal that Harrer joined Hitler’s SA or storm troops in 1933, at a time when Nazi activities were banned in Austria.

French director Annaud said in a statement quoted in the New York Times that he suspected Harrer had some Nazi connection prior to the war, but that after the war “he devoted his life to nonviolence, human rights and racial equality.” Harrer, who is 85 and lives in Austria and Liechtenstein, told the Austria Press Agency that he never carried out SS activities and admitted that “from today’s view, the former party and SS membership is an unpleasant thing.” He added that he lives with a “clear conscience.” The Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles said there is no evidence linking Harrer to Holocaust activity.

In 1938, Harrer made the first ascent of Switzerland’s precarious Eiger North Face—and earned a handshake from Hitler. He later became a sports instructor and joined the Nazi party in order, he claims, to partake in a government-financed Himalayan expedition. Without the membership, he insists, he would have had no chance of exploring the Himalayas—his life’s dream.

At the end of the expedition in September 1939, just as war broke out, Harrer and a companion were arrested by British troops in India. The two escaped an internment camp in 1944 and trekked through Tibet to Lhasa, a place few Westerners had ever laid eyes on. They soon became known to the country’s religious leadership, including the young Dalai Lama. Harrer became His Holiness’s tutor in math, English, and sports, as well as an advisor and friend. Seven Years In Tibet was ultimately translated into forty-eight languages.

Bedrock Buddhas

Officials of Afghanistan’s Taliban leadership threatened this spring to destroy two 2,000-year-old Buddhist statues they regard as an insult to Islam. One of the fourth-century Buddhas of Bamiyan, carved from sandstone cliffs, is the tallest standing Buddha in the world. The threat prompted United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan to appeal to political commanders in Afghanistan that the statues be left alone. So far, they have been unharmed.

Other parts of Afghanistan’s Buddhist past, including 1,700-year-old shrines at Hadda in the eastern part of the country, are being destroyed for more mundane reasons. According to a report by the Society for the Preservation of Afghanistan’s Cultural Heritage, trucks are hauling off stones from the Hadda shrines for use as building materials.

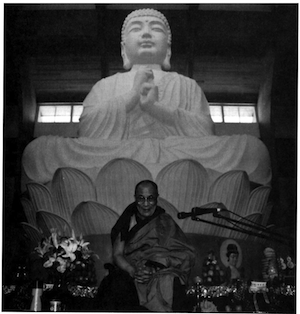

On Tour in the USA: The Dalai Lama

On May 25, the Tibetan leader His Holiness the Dalai Lama took part in the dedication ceremony for the Great Buddha Hall at the Chuang-Yen Monastery in Carmel, New York. The hall houses the largest Buddha statue in the Western hemisphere—a thirty-seven-foot statue of the Buddha Vairochana. His Holiness also gave teachings on emptiness and the Thirty-seven Practices of the Bodhisattva, and offered an Avalokiteshvara initiation at the Chinese Pure Land sect monastery. About 5,000 people turned out for the three-day event.

On the evening of May 29, the Tibetan leader gave a public talk at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City. The exiled leader spoke about harmony in diversity and encouraged peace and tolerance, especially in matters of race and religion. The crowd of 4,000 applauded when His Holiness predicted that the twenty-first century would be the “century of dialogue.” Before the talk, the Dalai Lama joined other Nobel Laureates, including Elie Wiesel and Oscar Arias, in signing The International Code of Conduct on Arms Transfer.

On May 31 the Dalai Lama was warmly greeted in Boulder and Denver, Colorado, where he gave public talks and attended ceremonies in his honor. He also attended the Naropa Institute’s “Spirituality in Education” conference.

June 2 found His Holiness in Santa Barbara, California, where he gave the inaugural lecture for an academic chair named in his honor, the XIV Dalai Lama Endowment for Tibetan Buddhism and Culture at theUniversity of California. His activities in the Los Angeles area included a conversation with the religious scholar Huston Smith, a public talk, teachings, and initiations at UCLA and the Thubten Dhargye Ling Tibetan Buddhist Center.

In San Francisco he attended a three-day conference called “Peacemaking: The Power of Nonviolence,” co-convened by Professor Robert Thurman, Tibet House, and the author Daniel Goleman. His Holiness, recipient of the 1989 Nobel Peace Prize, also participated in a public talk with fellow Laureates Rigoberta Menchu of Guatemala and Jose Ramos-Horta of East Timor.

For the first time ever, during his recent United States visit the Dalai Lama discussed issues ofhomosexuality, human rights, and Buddhism with a small group of gay and lesbian Buddhists and human rights activists. At the June 11 meeting in San Francisco, the Dalai Lama expressed his strong opposition to discrimination and any form of violence against gay and lesbian people and voiced support for full human rights for all, regardless of sexual orientation. He encouraged gay activists to rely on Buddhist principals of rigorous investigation and nonviolence as the foundation for their struggle for full equality. Participants were also heartened by the Buddhist leader’s willingness to re-examine traditional Buddhist teachings on sexual misconduct and homosexual behavior in light of modern scientific research, psychology, and changing social mores.

The Dalai Lama proposed the private meeting in response to a letter from Steve Peskind, a San Francisco–based writer and coordinator of the Buddhist AIDS Project, requesting clarification of teachings in two recent books by the Dalai Lama, Beyond Dogma (North Atlantic Books, 1996) and The Way to Freedom(HarperCollins, 1994).

The Dalai Lama opened the meeting by saying “Thank you for trusting me in coming here.” Reading the Tibetan text of Lam Rim ethics, he noted that the traditional teachings, dating back to the Indian Buddhist philosopher Ashvaghosha, assert that sexual misconduct for all Buddhists, heterosexual and homosexual, is determined by “inappropriate partner, organ, time, or place.” Inappropriate partners include men for men, women for women, women who are menstruating or in the early stages of nursing, men or women who are married to another, monks or nuns, and prostitutes “paid for by a third party and not oneself.” Sex with the “inappropriate organs” of the mouth, anus, and “using one’s hand” also constitute sexual misconduct for all Buddhists. Inappropriate places include Buddhist temples and places of devotion. Proscribed times are “sex during daylight hours” and “sex more than five consecutive times” for heterosexual partners.

In his recent publications, Peskind noted, the Dalai Lama reiterated these teachings “with no qualification for cultural context or for modern scientific findings and social history.” In the letter sent to the Dalai Lama, Peskind expressed concern about the implications of these teachings, saying their presentation “supports the climate of international psychological, spiritual, physical, social, and political discrimination, violence, and human rights violations against gay people and others.”

In the meeting, the Dalai Lama made it clear that violation of any of the moral precepts, including killing, does not and cannot disqualify someone from being a Buddhist. But some participants were eager for more discussion of the teachings. According to Peskind, His Holiness “did not clarify how sex as an expression of emotional intimacy, moderate recreational sex, or gay tantric sex impedes the path to full awakening, freedom, and peace of heart.” Buddhist writer Scott Hunt observed that while the Dalai Lama noted that the teachings in question may be culturally specific to ancient India, he “did not substantiate the positive effects of the teachings for Buddhists of this time.”

Among those attending the meeting were Steve Peskind; Eva Herzer, president of the International Committee of Lawyers for Tibet; José Cabezón, writer and Buddhist scholar; K. T. Shedrup Gyatso, an ordained gay Tibetan Buddhist monk and director of the San Jose Tibetan Temple; and Rabbi Yoel Kahn, a leader in the lesbian and gay Jewish community.

Following the meeting, José Cabezón said, “It is wonderful to see a religious thinker of the caliber of His Holiness the Dalai Lama grappling with the issues of sexual ethics and especially the rights and responsibilities of gay and lesbian people in such an open, empathetic, and rigorous fashion

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.