Mom thought Saturday would be a good day to die. Definitely. No one expected to see her that day all dressed up in her white uniform with the shiny brass RN badge on her lapel. Harlem Hospital’s prenatal unit would be closed, and Saturday meant no school for us kids. Grandpa would drive us across the Brooklyn Bridge for the weekend. It was a sort of free day for Mom. Yes, this was her plan: suicide on a sunny Saturday.

How do I know this? Because before she died, she shared her memories of this day with me in detail.

Manhattan sparkles in spring, and that day when Mom glanced at the glistening New York City asphalt, she felt a deep relief. She had been contemplating death for years. When Dad moved to Mexico City with his secretary, everything unraveled for us four. Mom’s drug addictions kept her in a continual cycle of hate, anger, and despair—a cycle that always led to her violent abuse of me and my two younger sisters. Inside our swanky West Side apartment, we were living in hell. Now, after a decade of fruitless attempts to heal, Mom was broken in body and spirit and consumed with self-hatred. Suicide seemed like her only out. A few days earlier she had written in her journal: “How mercilessly I beat them, almost daily. I am alone. I’m using mescaline, pot, speed, psychotropics, and sleeping pills, sleeping around, and just so beaten up by life.

I will kill myself.”

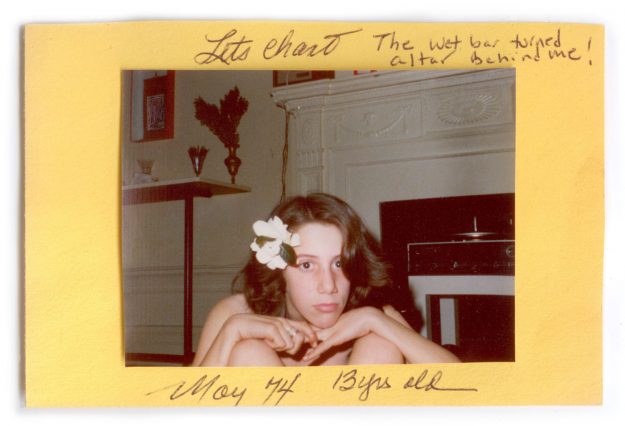

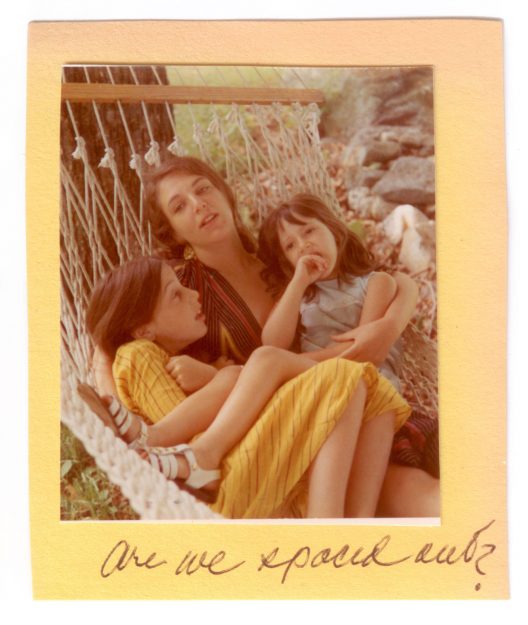

Something else she knew: this Jewish American princess would not go down with bad hair. Before overdosing on barbiturates, she would go to the beauty salon. She was only 33 and she didn’t need color treatments, but she had always hated her natural curls. As Marilyn, the stylist, sprang into action, Mom tried to relax in the soft leather chair. Her hair fell back into the shampoo bowl, her head filled with worries. Who would take the kids? What would her mom and dad think—would they even care if she left this earth? Oh, but it felt delicious and decadent to have Marilyn massage her scalp. She decided to enjoy the moment.

“How are the kids?” Marilyn asked.

“They’re great,” Mom smiled.

She had already decided that she would call her boyfriend for a final fling. He was a top-notch New York City narcotics officer, and whenever he apprehended his dealers, he would confiscate their drugs and save the best to share with Mom: uppers, downers, mescaline, Quaaludes, psychedelics, hashish, and new strains of hallucinogens. Remembering this period of her life, Mom later wrote in her diary: “Who the fuck was taking care of my babies? Boy, our apartment was a fucking den of sex and drugs. Poor Leslie, I remember her so depressed and how I would beat them if they tried to get anything they needed from me. . . . How I hated having to take care of them and how I wished they would all go away.”

As the hum of the blow-dryer filled the air, Marilyn exclaimed: “You look so beautiful!” Though Mom felt ugly, she fixed her eyes on herself in the mirror. Staring at her own blue-green eyes, milk-white skin and finely chiseled nose, she ignored Marilyn’s chatter and felt sharp pains in her stomach. Her insides cringed at the person she had become.

She had tried to stop beating us. She had tried to heal herself though primal scream therapy, rational emotive therapy, Gestalt therapy, psychoanalysis therapy, Freudian therapy, Synanon Game therapy, traditional therapy, and a myriad of drugs. Nothing had worked, and with each failure her rage toward us three intensified.

Worst of all were the night beatings. Speed possessed Mom at about midnight and did not leave her bones until about three a.m., when her sleeping pills and smooth vodka kicked in. We expected it nightly. Like chameleons, we adjusted to our maniacal mom. Over time, being dragged around the smooth hardwood floors by our long wavy hair no longer fazed us. She would hurl guttural screeches at us for hours and then make us clean, sweep, dust, fold, rinse dishes, change bed sheets, organize toys, and wet-mop the floors. We wanted to live, so we scoured the house and didn’t utter a sound during the craziness. In a sleepy daze, bearing her slaps and kicks, we cleaned and then cleaned what was already clean until she finally fell asleep.

As Saturday’s sun set in gold and red on the Hudson River, Mom decided to defer death. She would try one more thing before suicide.

After I was born, Mom had wanted to lose the pregnancy weight quickly because my dad hated plump women. When she told her doctor she needed to get thin fast, he immediately prescribed diet pills. As a nurse, she should have known about the link between amphetamines and aggressive behavior. Once she was addicted to uppers, Mom couldn’t sleep, and that’s when she started to accumulate an unlimited supply of sleeping pills. Full-blown amphetamine psychosis paired up with the numbness of sedation, and her heavenly hell began.

Her hair was finally dry now, and Marilyn set it with huge curlers to eliminate the frizz. Mom envisioned herself going back to the apartment, undressing, and walking around naked, singing her favorite sad Billie Holiday song, “God Bless the Child.” She’d have a glass of vodka with a bit of tonic water and then overdose.

While Marilyn was flattening the final section of hair, Mom began to plan her suicide note. “Marilyn, look!” a voice exclaimed. Mom turned from her own reflection to see the face that belonged to the voice. “I brought you a copy of the book I was telling you about, Buddhism: The First Millennium.”

The dark-haired woman, Melanie, was radiant. She was telling Marilyn about an ancient chant—and how it could buoy the spirit. Mom had never seen anyone look so happy from the inside out. “What are you on?” she asked. “Please tell me.” Mom wondered what drug could be on the market that she hadn’t yet tried.

Melanie shot a look at Mom, “No, no, I’m not on any drugs. Have you ever heard of Nichiren Buddhism? That’s my practice. It’s a devotional path that involves reciting and meditating on certain passages of a scripture called the Lotus Sutra.” Melanie went on to tell Mom how invoking the Japanese title of this sutra, “Nam-myoho- renge-kyo,” a practice known as the daimoku, could change her life by drawing out her inner buddhanature. “As your voice makes vibrations, you shift your own life condition.” Melanie shared the translation of the daimoku, “Devotion to the mystic law of causality through sound” (or “through the Lotus Sutra”), and how myo can also mean “to open” or “to revive.”

Mom laughed loudly. She still wondered if Melanie was stoned, but Melanie continued talking about how her tradition believed in the boundless potential we all possess. She told Mom, “This practice can alter destiny without drugs.” In spite of herself, Mom couldn’t help but wonder: was it possible this meeting was more than mere coincidence?

Her hair was finally free of frizz, and Mom stood up from her chair. “You wanna teach me this verse today?” she asked Melanie. “My kids aren’t home, and I need this now!” Melanie must have sensed the urgency in Mom’s voice. “Sure, honey,” she said. “Let’s go to your house, and I’ll explain more.”

They left the salon and got on the subway. On the train, Mom poured out her story: her grief at abandonment, her drug use, her abusive behavior toward her daughters, and the lure of suicide. Melanie quoted the president of the Buddhist organization Soka Gakkai International, Dr. Daisaku Ikeda: “The act of chanting Nam-myoho- renge-kyo is a drama of profound communion or interaction between ourselves and the universe. . . . It is the revolution that rewrites the scenario of our destiny.” Mom’s body shimmied and shook during the subway ride. Was she in a dream? It all seemed so surreal. Was it possible that she could become a Jewish American Buddhist?

As Melanie stepped into the apartment, she passed the large barrel of marijuana in the entryway and asked Mom where they could set up “a spiritual corner.” They settled on turning the wet bar into an altar. Melanie and Mom placed their hands over their hearts and began to make sounds. Within moments, the harmonics of their vibrating voices began to create a feeling of relief for Mom. Her heart hummed and her soul was soothed. She tasted hope, something sweet. An intimation of unconditional love. A stranger had saved her sanity that day.

As Saturday’s sun set in gold and red on the Hudson River, Mom decided to defer death. She would try one more thing before suicide. In her journal that evening she wrote, “And that’s when I started to chant and began to see my life. . . . Death can wait.”

When we three kids got home from Grandma’s the next day, Mom stormed in my room and declared, “We are going to be Buddhists now.” “What the hell?” I said. “No way! Have you gone completely crazy?” “No,” she said in a calmer tone. “I think this might help us, help our happiness along. It seems positive and we are all gonna try it.” As Mom spoke, I glanced at the transformed white marble wet bar, now missing its bottles of bourbon, gin, vodka, and whisky and the shiny glasses.

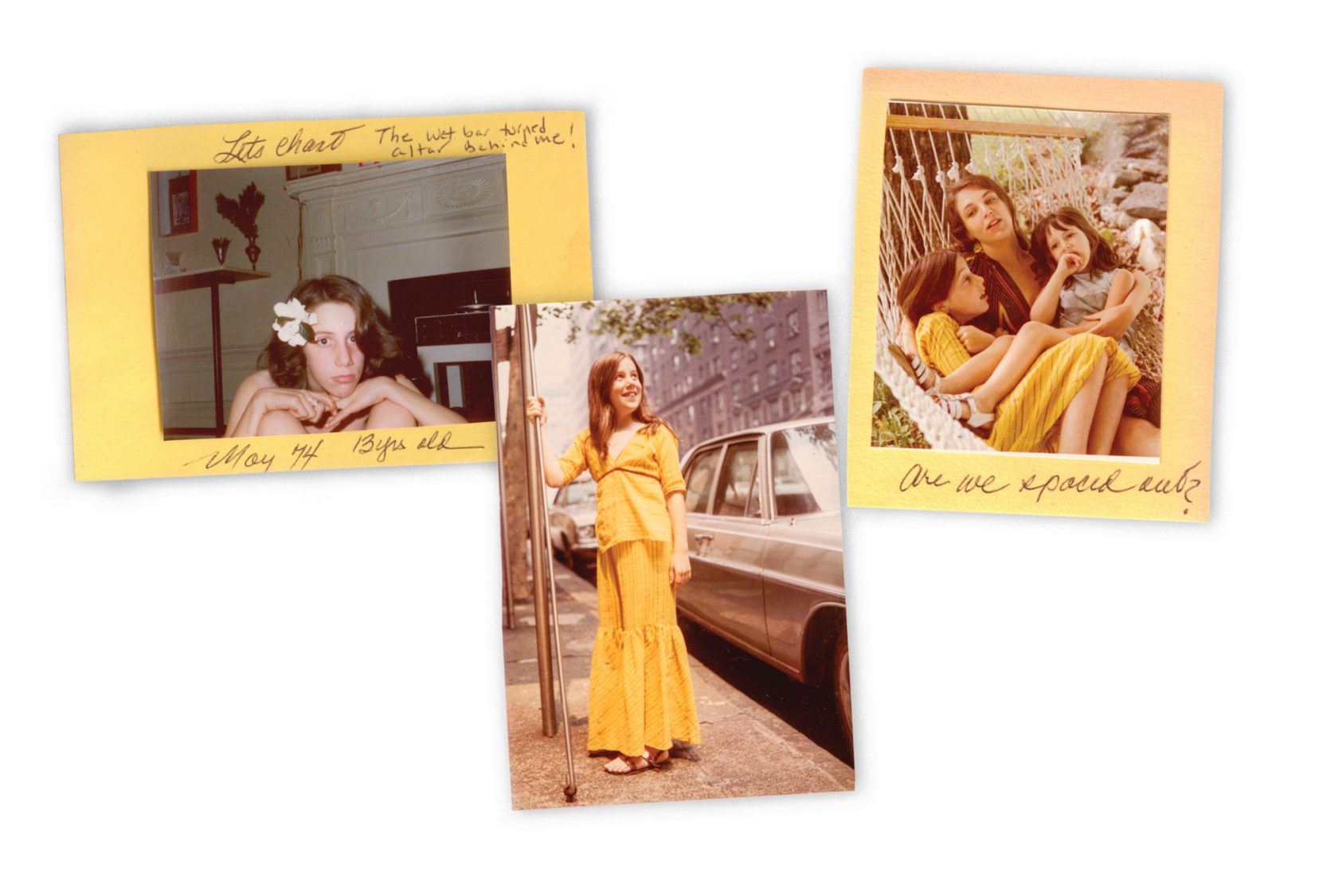

To me it was clear that Mom had finally flipped. Her bar had become a Buddhist altar. Her drug-and-desire table now featured a sacred scroll, white candles, green leaves sprouting from a clear vase, a bowl of apples and bananas, green incense lying flat in a wooden box, a tiny sparkling gold pillow supporting a black bell, and a white lotus-shaped water dish. At 13 years old, I was defiant. “No, no, no, no, no,” I said to her. “If you want to make strange sounds, go ahead, but I am out.” As the oldest of three, my mission had always been to manage Mom’s hysteria and brace for our regular beatings. I felt a semblance of safety by thinking I could control her next rage. But mumbo-jumbo chanting? I had no strategies for that. And besides, I was numb to the notion of having peace in our violent home. In my mind, I was so much smarter than my mother was. I was done with her mishegas, her craziness, and I wanted nothing to do with another one of her futile attempts at self-improvement. “You are certifiably crazy,” I told her. But she just looked at me and said, “Would you try this practice with me if I make you a bet?”

“What type of bet?” I asked warily.

“Here’s the deal,” Mom said. “Chant with me twice a day for at least 10 minutes for one hundred days, go to one Buddhist meeting a week, and study this teaching 5 minutes a day. If after this trial you don’t see a positive effect, I promise I will quit.”

Just then Mom was already experiencing a very palpable relief from the chanting, a shift in her energy—but I didn’t know this at the time. “Leslie, I dare you to become happy,” she told me.

My mom was smarter than I thought. She knew how to get to me. My teenage mind thought, This is great—I can get Mom to quit this charade. I made her promise me in writing that unless every single thing that I chanted for came to be, she would stop. “Mom, you’re on, but I’m gonna win,” I told her.

On the first of the hundred days, I sat on a cushion facing the wet bar. I recited “Nam-myoho-renge-kyo” with fervor to win the bet; in my mind I was smirking nonstop. But over time, as I chanted the daimoku with her twice a day, deep down I began to wonder: Could this work? In spite of myself, the simple act of making the vibration was helping my defeated spirit rise just slightly higher. The sounds sparked a hint of what happiness might feel like. But of course I couldn’t tell Mom what I was feeling.

By the twenty-fifth day of the bet, I felt a tremor of joy deep down. I was only a quarter of the way through the experiment, but already I was beginning to question my entrenched belief that my life would always be terrible, as it had for the last ten brutal years. Did Mom have buddhanature? Did I? Was transforming our horrific family karma possible?

By the fifty-fifth day, still set on disproving this to Mom, I realized I had a problem: Mom was winning the bet. Everything on my prayer list was manifesting as I continued to repeat the daimoku, but more importantly, I felt happier and noticed that Mom seemed happier too. Something was shifting, but I did not want to admit it.

I followed Mom’s terms every day of the test. I chanted twice a day, went to a weekly meeting, and started learning how to turn the wheel of cause and effect in my life by transforming my obstacles into an invitation for inner growth. In a lecture, Dr. Ikeda wrote, “The times when we experience the most intense suffering, unbearable agony, and seemingly insurmountable deadlock are actually brilliant opportunities for doing our human revolution.” As I learned about this philosophy, my inner transformation truly began. I felt a kind of cellular vibrational shift, as if molecules were moving in my favor. Prior to this bet, I often wondered whether happiness really existed or was just a fantasy on TV. But each day as I chanted, sorrow lifted and hope started to replace it.

When the one hundred days ended, I realized definitively that I had lost the bet. I tested the power of the words initially in a very superficial way. But what I most remember was that—despite my disbelief in Buddhism—my despair was lifting. Pressing my palms together as I repeated the daimoku, I felt a smiling from within that I had never felt before. Mom knew she had won because I kept chanting and never asked her to quit. I had reluctantly joined her on this strange spiritual quest, and now, at the age of 13, I felt inside that I had become a full-fledged Jewish Buddhist. Though it might have been invisible to others, I felt like a once raggedy orphan who was now wearing a shining tiara of hope.

Life for us four improved day by day. Mom’s drug use and rages slowly decreased. Gradually, as I learned that every obstacle in life contains its own source of transformative energy, my own practice expanded beyond the realm of tangible desires and focused on a deeper spiritual understanding. This was the key to the striking vitality that my mother had seen in Melanie—and that, in the depth of her despair, she knew she wanted for herself.

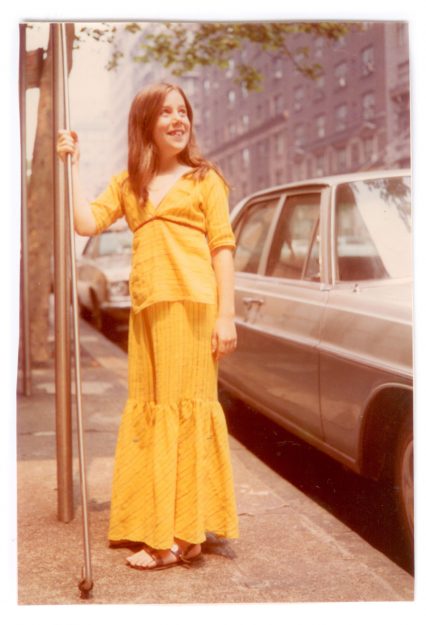

My mother and sisters and I have had many challenges on the road to healing. But as our mentor Dr. Ikeda writes, “When you look back, you’ll find that the difficulty that was causing you so much heartache became an opportunity to dynamically expand your life-state.” Certainly that turned out to be true, both for my mother and for me. And now, in retrospect, it almost seems like a wonderful joke. My mother went to a beauty parlor that Saturday morning because she didn’t want to leave this earth with bad hair. Instead she found her way to a very different kind of beauty, a beauty that was still shining from her face when, shortly before her death in old age, she asked each of her daughters once again for forgiveness. It was a beauty that she dared me to find for myself—in a bet that, for the rest of my life, I will be grateful for having lost.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.