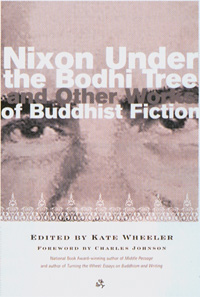

Nixon Under the Bodhi Tree

And Other Works of Buddhist Fiction

Kate Wheeler (Ed.)

Boston: Wisdom Publications, April 2004

280 pp.; $16.95 (paper)

Buddhism has been infiltrating English-language literature since Rudyard Kipling’s Kim more than a century ago, and vigilant readers may have noticed a growing number of novels with Buddhist themes. But you won’t see a “Buddhist fiction” shelf in most bookstores, or in local libraries, and you’re more likely to stumble upon a poem than a short story in your sangha newsletter. Buddhist fiction is out there, but it hasn’t been easy to find.

Until now. In Nixon Under the Bodhi Tree, Kate Wheeler, a Tricycle contributing editor, has assembled a marvelous collection of stories inspired, in one way or another, by Buddhism. They range in length from a few lines to several thousand words, and cover topics as diverse as driving, acting, politics, food, birth, rebirth, love, lust, death, murder, suicide, animal adoption, and lawn mowing. Half of the thirty stories are published here for the first time. Certain themes emerge—we meet monks and nuns of various sorts, and earnest and not-so-earnest meditators in foreign lands—but there are plenty of surprises. Keith Heller’s previously unpublished “Memorizing the Buddha,” about a tailor whose prodigious memory wreaks havoc until it is put to use preserving the dharma, provides a vivid reimagining of life in the sleepy Sri Lankan village of Ratna, 450 years after the Buddha’s death:

Ratna’s only road wound through dense undergrowth, and long ago wild brambles and creepers had been allowed to obscure the passing traffic with a natural latticework of branches. This helped to preserve the village from political upheavals and the various temptations that too much wealth and knowledge often give rise to, yet the isolation also doomed the village to being forever forsaken, its people as ignorant of the world around them as they were of the stars above.

Heller’s fable is a stark contrast to Jan Hodgman’s “Tanuki,” the much darker story of Koen, a Japanese nun living at a remote mountain temple. Hodgman’s powerful tale is filled with haunting images of loneliness and self-sacrifice:

Every morning at four Koen rose from her bedding on the straw-matted floor, dressed in her black monk’s robes, lit a stick of incense in front of the memorial plaque dedicated to her aborted baby (her husband convinced her that the threat of deformity was great since she had contracted mumps during her pregnancy), whispered a short sutra, and climbed the rocky path to the meditation hut. Her feet knew the bumps and turns of the trail even on the darkest of nights, though others found the leaf and moss-covered rocks treacherous.

Like so many of the stories here, “Tanuki” is wonderfully understated. We don’t hear about the abortion again (and her aborted marriage is described only as “tasteless”), but the image lingers, helping us understand why Koen chooses the solitary existence of a monastic, negotiating her way along that treacherous path.

There are many other gems. Ira Sukrungruang’s “The Golden Mix” is a funny and moving account of an ordinary guy who happens to meet the Buddha. Kira Salak’s “Beheadings” weaves a complex narrative about a journalist whose guilt-ridden brother takes refuge in Cambodia, and concludes with a startling vision of redemption through practice. As novelist and scholar Charles Johnson, also a Tricycle contributing editor, writes in his elegant foreword, these stories succeed because they “dramatize the dharma by taking us intimately into the lives of [their] characters,” and show us “how the Buddhist experience is simply the human experience.”

The book’s title story, an O. Henry Award-winner by Gerald Reilly, is a masterpiece. Its main character is Dallas Boyd, a failed actor who finally finds his true calling playing Richard Nixon in an obscure play. Boyd practices Tibetan tonglen meditation (taking on the suffering of others and sending them relief). Reilly conveys the mystical connection between the actor and the former president in warm, lyrical prose:

It is simply indescribable doing this meditation with Dick Nixon. Some days he finds himself thinking about Cambodia and all the bombs that were dropped and the black karma coming so thick that it clouds out the sun until Dallas feels he can hardly keep breathing and then, just before he panics, he is letting go, all the bliss and blue skies exhaling out to Nixon. It works counter to everything in the life of a struggling, up-and-coming actor, what’s supposed to make up your most basic nature, your survival instinct. You’ve changed, friends told him. He knew he had grown altogether more somber; he felt like he was wearing a jacket and tie all the time now. He was dying and yet he was worrying about poor Dick Nixon.

Wheeler’s own crisp, smart short stories, collected in Not Where I Started From (1993), would have been very much at home in this anthology, but she has chosen not to include them. In her introduction she explains that her precondition for taking on this project—conceived by Wisdom Publications’ Rod Meade-Sperry—was that “we would not define what the nature of the Buddhist connection had to be.” This ecumenical approach results in a few selections that contain no explicit references to Buddhism and probably wouldn’t be associated with the dharma if read in another context. Some others don’t seem to be fiction: Pico Iyer’s poignant contribution, “A Walk in Kurama,” is taken from his memoir The Lady and the Monk: Four Seasons in Kyoto, while Diana Winston’s entertaining “Mi Mi May” was originally published as a nonfiction article in Tricycle (Summer 2001). The excerpts from two novels—Keith Kachtick’s Hungry Ghost and Doris Dörrie’s Where Do We Go From Here?—are not entirely satisfying in their shortened form, but they at least whet our appetites for the complete books.

Not everything could be squeezed into a single volume. (Wheeler tells us the submissions “filled two large cardboard boxes.”) Buddhist-inspired genre fiction—such as Eliot Pattison’s popular series of Tibetan mysteries—is unrepresented, as is the work of Asian authors and most others not writing in English. But what’s omitted only serves to underscore what a vast landscape Buddhist fiction has quietly become. Taken as a whole, this volume is surely a milestone in Western Buddhist literature—and a book that fiction-lovers, Buddhist or otherwise, will very much enjoy.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.