“Mr. Glassman, can you hear me?”

Bernie, lying in bed, stares intently at the doctor.

“Can you raise your right hand, Mr. Glassman?”

Nothing moves. Dr. Glassman, I think numbly. He’s a mathematician; it should be Dr. Glassman.

“Can you say something, Mr. Glassman?”

Bernie’s dry lips twitch, say nothing. His eyes veer toward me, toward his daughter, Alisa.

We’re in Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Massachusetts, two days after his stroke. It’s a beauty. He’s lost all feeling and movement in his right side, and he can’t say a word. His sister, Sally, told me: “Bernie couldn’t talk at all for the first two years of his life. We all wondered what was wrong, but once he started he never stopped.” Never stopped talking, planning, strategizing. But he’s stopped now.

I think back to a conversation we had a month earlier. On the verge of turning 77, Bernie dropped most of the administrative and teaching load he still handled for Zen Peacemakers, which he’d founded in 1979. Back then it was a local New York sangha of students working in the inner city of southwest Yonkers, providing jobs to the unemployed at the Greyston Bakery, building homes for families with no homes, and running a childcare center and an AIDS facility. Almost 40 years later, it was an international family of Zen practitioners and affiliates actualizing their understanding of oneness through service and social action throughout the world. By the end of 2015 he had canceled traveling and teaching engagements and let go of leading bearing-witness retreats, which he had done for many years, at sites of great suffering: places like Auschwitz-Birkenau, Rwanda, Bosnia, and the Black Hills of South Dakota.

I sat down to talk to him one day: “Bernie, I’m seeing you with time on your hands for the first time that I can remember. But I have a lot to do, and I’m not much for hanging out or entertaining people.”

“I know.”

“So what are you going to do?”

“That’s what I don’t know. But I’ve found that when I let go of things and make time, something new pops up.”

Less than a month later he has a major stroke, six days before his birthday.

A tiny movement of one toe informs the doctors that his right side is not fully paralyzed. He raises his bloodstained left arm anchoring multiple wires and IV needles, perplexity written all over his face, and I, along with Alisa and Bernie’s assistant, Rami, tell him: “You had a stroke. You’re in the hospital. You’ll be fine.” We repeat this 20 minutes later, and 20 minutes after that.

“Fine” means different things. First it means you’ll probably live. Then it means you’re going into rehab, where you’ll regain some things, probably not all, we don’t know how much. And it’s in rehab, with Bernie propped up like a limp doll to have his body, bed, and linens cleaned by nursing aides, that we finally see the loss. He leans against one side of the bed, I stand on the other, and we look into each other’s eyes. I feel like a newborn seeing things I’ve never seen before, like the face of my husband slowly realizing that he can barely move, can’t sit up never mind stand, can’t toilet himself, and that his terrific mind has changed. Don’t you dare shut your eyes, I tell myself. Don’t look away just because everything has broken down. Life is showing you something completely new unless you mess it up, avert your gaze, argue with the staff, google for alternatives.

His speech comes back first. Why does that not surprise me? In fact, within a few weeks lots of words come back, except for one. “I—can’t—remember—that—word,” he says very slowly from his bed.

“What word is that?”

“What—I—had.”

I think a minute. “You like bowling, right?” He loves The Big Lebowski. “Think of bowling. What happens when you get all the pins down?”

“Strike,” he says right away.“Stroke. Bowling-strike-stroke.”

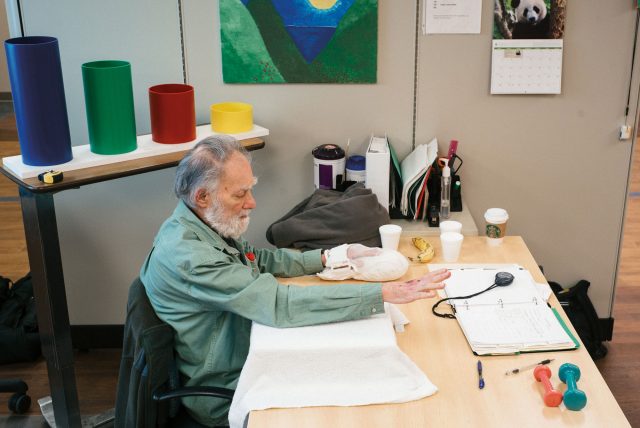

It takes four people to help him take his first steps: Bernie holds on to a rail with his left hand, a physical therapist out front gives directions, an assistant picks up his right foot and puts it down step after step, and I push the wheelchair behind him in case he tires. Like most of us, Bernie moves his chest forward and assumes the legs will follow. That doesn’t happen now.

“Whoa, we don’t want you to fall, we want you to move,” Tara, his remarkably cheerful physical therapist, tells him.

“Before my—” he pauses, trying to remember, “bowling-strike-stroke I used to move pretty fast.”

He had the reputation of prodding and pushing students to always do more—bake more cakes, build more homes, do more street retreats, bear witness to more places of genocide, organize more peacemaker circles in more countries—with the result that they often felt overwhelmed by both his pace and his scope. “I took so-and-so around Greyston,” he’d tell me upon his return from Yonkers. “Did you show him where the bodies are buried?” I’d ask. He told me that his teacher, Maezumi Roshi, used to caution him: “Tetsugen, when you move fast, people stumble.” Now Tetsugen, known as Bernie, moves very, very slowly.

“Don’t stand on the leg you know can hold you,” Tara tells him, “stand on the leg you don’t know can hold you.”

Bernie tries to say something—about not-knowing?—but the words don’t come out; he sighs, lets it go.

“Curl the toes on your right foot. Read this sentence. Shrug. Move your right shoulder. Flatten the knee. Try to swivel. Where’s your right foot? Always check your right foot before you stand. Lift this finger. Keep the elbow straight. Do it again. Roll over. Speak louder. One more step. Now one more. Again. Again. Again. Where’s your right foot!”

There are moments of darkness, but not many. He swings his legs slowly over the edge of the bed, reaches for the padded socks with his left hand and puts on the pair of heavy shoes he’ll wear winter and summer, and suddenly his flailing right arm shoots up: “Eve,” he tells me, “I just hit my face with my right hand, what do you think of that?”

The speech therapist reads questions out loud:

“Tell me something that is rough and round.”

Bernie: “A head with a crew cut on it.”

“Three things that get smaller when you use them.”

“A sponge. A penis. A chocolate bar.”

“Three things that slither.”

“A snake. A woim. A goniff.”

“Three things that hop.”

“A kangafoo. A one-footed Frenchman. A bounceria.”

“Bounceria? What’s a bounceria?”

“I made it up.”

Mariola Wereszka and Godfried de Waele, two European Zen Peacemakers, arrive to help us, and Bernie grows thoughtful. “What’s the matter?” I ask.

“Mariola asked me—what is the meaning of Zen,” he says. “I have been asked that question hundreds of times and I always had an answer. This time I didn’t know what to say.”

“Mariola asked me—what is the meaning of Zen,” he says. “I have been asked that question hundreds of times and I always had an answer. This time I didn’t know what to say.”

Seven weeks after his bowling-strike-stroke, Bernie comes home to a downstairs office turned into a sunny, Get-Well-card-bedecked bedroom, with dozens of goldfinches outside at the feeders, grab bars in the bathrooms, banisters alongside the stairs, and a ramp in the garage. I got organized, lifted weights, rolled back rugs, directed furniture moves and alterations, checked things off a long list, in short: Gibraltar. If there are two things I know, it’s how to be strong and how to spring into action. Springing into nonaction is something else entirely.

Two days later, on a Friday evening when the two of us are alone for the first time since the bowling-strike-stroke, Bernie crashes to the floor. They warned us it would happen, but it’s a shock, followed quickly by a second one: he can’t get up again. In fact, he can’t do anything to help himself. I try to pull him up from different directions, I push, encourage, implore. Nothing.

“I—need—a—pillow,” he says weakly from the floor. “I—need—a—blanket.”

I call 911. The wait feels like forever. Bernie shuts his eyes while I sit by numbly, staring at a wall and a world where willpower and competence have no meaning. Within minutes the first responders arrive to find an elderly man supine on the wooden floor in a back room, under a blanket, his wife sitting frozen on the adjoining bed.

As his speech improves, Bernie begins doing video conference calls with groups of dharma successors. “I don’t want to teach,” he says to the faces on the screen, “I want to hear from you.” But they want to hear from him, so he tells them that after his bowling-strike-stroke, resting between therapies, he’d entered a state of meditation that took him into the most profound space of not-knowing he’d ever experienced. It felt so natural and organic that he thought nothing of it until someone asked him if he was bored lying in bed and staring into space.

But when he’s asked more questions about that, tears come into his eyes. “You don’t understand,” he says. “The real question is what does this have to do with being a mensch, a human being? If we can’t answer that, what are we doing?”

I’m not used to seeing him cry.

In April a Dutch Zen Peacemaker, Petra Hubbeling, organizes a plunge to help African, Asian, and Middle Eastern refugees at camps in Piraeus, Greece. “Plunges” are how we refer to bearing-witness actions, usually initiated by a Zen Peacemaker, that self-organize through Facebook and other social media. They are plunges into the unknown, for there is little central organization, setup, or game plan; the group arrives, bears witness to the situation at hand, and works accordingly. Petra is joined by people from as far west as the United States and as far east as Australia.

I grow restless. Bearing witness has been a practice that Bernie and I have shared for many years. We have already missed planning meetings with Native Americans for the summer retreat in the Black Hills. We will miss the plunge at Cheyenne River Reservation in the summer and the fall gatherings at Standing Rock. There were years when we spent at least a third of our time traveling, and I’d count the days and weeks till we returned home.

“Janet said I can walk without you,” Bernie tells me proudly. “I can walk on my own.” He has been gingerly walking with a four-prong cane for several weeks, always with a belt around his waist and someone holding the belt’s other end to prevent a fall. A village of people has supported him with every step, including Godfried and Mariola, Rami, Reuven Goldstein (Bernie’s acupuncturist); fellow board members Grant Couch and Chris Panos overseeing the Zen Peacemakers’ work and organization from a distance, and gifts, prayers, and loving wishes from around the world.

But there is nothing impeccable about walking alone. In fact it’s downright scary. Bernie’s foot drags, his knee buckles, his leg shifts from side to side; Hamlet never felt so undecided. And to make things worse, the Great Obstructor has appeared.

In his 13th year, our dog, Stanley, is completely deaf and at least half blind from cataracts. Gleefully, he accompanies Bernie everywhere, finagling his way between cane and legs, squatting down on his belly right between Bernie and the chair he’s aiming for, or else conveniently turning into a statue at Bernie’s approach.

“Obstructor!” Bernie shouts out, pounding the floor with his cane.

Therapists warn you that most falls happen on account of rugs and pets, but Bernie appreciates Stanley because the dog makes him figure things out. If Stanley’s blocking his chair Bernie has to circle around to get in from the other side. When Stanley blocks the hallway Bernie has to walk around him, and when the dog suddenly stops going down the stairs, as is his wont, Bernie has to come to an abrupt stop, too, without falling.

Stanley guards the bathroom with his life. Bam! bam! goes the cane on the floor, like a modern kyosaku, or “wakefulness stick.” “Obstructor!”

Stanley, in his great wisdom and compassion, doesn’t move.

“Maybe we should pay him a salary,” I suggest.

There’s a Zen koan made famous by the 18th-century Japanese Zen master Hakuin Ekaku: What is the sound of one hand? We know the sound that two hands make when they come together, but what is the sound of one hand?

Bernie can’t feel his right arm or hand. The fingers are clenched tight unless we put his hand in a splint, which can be painful, and the arm automatically bends at the elbow. His right hand invariably lies between us on the bed like some strange, floppy thing, splotched with red spots, blue bruises, and lots of Band-Aids. In the early days I’d open my eyes to see him examining this object in bewilderment. What is this? What is it doing here?

“That’s your arm, Bernie.”

“Is that so?”

Sometimes he slaps me with it in the middle of the night, which he never feels.

One day he looks down at both our arms. “That’s funny. My watch is gone.”

“What do you mean?”

“There’s a different watch on my arm,” pointing at the rose gold watch on my wrist.

“That’s my watch, Bernie, that’s my wrist. Your watch is around your wrist, look!”

He contemplates it for a long time. “Funny,” he says slowly. “All my life I’ve talked about John and Mary.”

He’s referring to his most basic teaching on the one body, which he has repeated many times: “Imagine this is Mary,” he’d say, pointing to his right arm. “And this,” pointing to his left, “is John. Only Mary and John don’t know they’re one body, they think they’re separate. One day John gashes himself. Mary looks at all the blood dripping and says, ‘Yuck, get that mess away from me.’ Or she thinks: I’m not a doctor, if I try to help John I’ll get dirty, or I’ll get sued. What happens? John dies, Mary dies, Bernie dies. But one day Mary and John go through an epiphany, or a great enlightenment experience, and they realize they’re one body, they’re Bernie. So now when John gets hurt, Mary doesn’t even think about it. She goes to the bathroom, shoves John under the water to clean away the blood and bandages him up.”

“I can’t feel John,” he now says. “I can feel Mary, but I can’t feel John.”

A month after beginning to go up and down the stairs, he’s thinking of going someplace else.

“So Bernie,” Jean says on Skype as we both look at her face on the screen, “what goal do you want to achieve out of your work at our clinic?” She is interviewing Bernie for intensive walking therapy at the clinic that Edward Taub, a giant in neuroplasticity, founded in Birmingham, Alabama.

“I’d like to be able to go to Auschwitz,” Bernie says.

Jean, bless her heart, doesn’t so much as blink.

“I want to be able to walk all the way to the Selection Site where we sat, like Marian did,” he tells me later.

At our retreat at Auschwitz-Birkenau, we sit by the train tracks at what was once the Selection Site. Marian Kolodziej was a leading Polish stage designer and camp survivor who kept silent about his experiences for five decades, suffered a stroke, returned to Auschwitz, and spent his remaining years creating his Labyrinth, large murals hung in the cellar of a nearby Franciscan monastery showing emaciated skeletons holding their empty bowls while surrounded by goblins with sharp teeth and roaring, rapturous grins. But the artist was every bit a koan as his creation, for he harbored no hatred toward anyone. He would sit on a chair in our circle, leaning a little forward on his cane, contemplating the camp he helped build as one of the first Polish prisoners sent to Auschwitz. By his side sat a beautiful woman, Halina, his wife. In the end there is only love, he would say.

In November, ten months after his stroke, Bernie goes to Poland. He can’t walk that long, long way down the tracks. But he gets to the church cellar to see Marian’s pictures; he visits the lonely tree in the center of the big ash field in back of Birkenau, the one by the small crematorium they called “the little white house,” and finally the hospice that was built in the town of Oswiecim, one of many undertakings that have come to fruition out of this 21-year-old retreat. In an evening council he speaks of how much he loved Marian, and when he leaves the central circle he totters back to his seat without his cane because he left it elsewhere.

“Now what?” I ask him when he returns. He’s glad he went, but the long flights exhausted him and he had to sleep for three days.

He doesn’t know. Something will pop up.

Nothing Solid

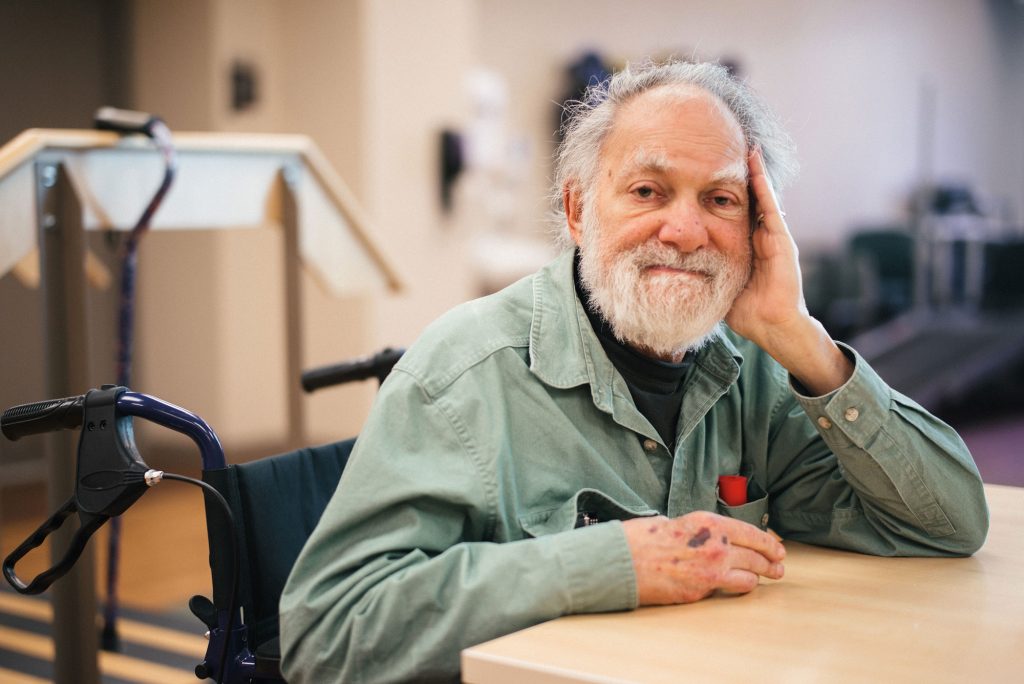

Bernie Glassman speaks about his stroke and rehabilitation.

You’ve been a longtime advocate of what you call “plunges,” retreat experiences that are designed to drop you into a place of not-knowing. Would you consider the stroke to have been a kind of life plunge for you? The term “plunge” came out of the idea of plunging into water when you’re afraid of getting in. You don’t go thinking about it too much—you just plunge. But the stroke led to more than a plunge. Or it was still a plunge, but a plunge like I’ve never had before.

How so? I’ve been doing a lot of rehab to recover from the stroke, and in between the exercises, I need to rest. As I lay there, it turned out I was plunging into a space I had never plunged into. I had no thoughts, no thinking at all. I didn’t think much of it at the time.

During rehab the doctors would tell me that I’ve been moving forward much faster than a lot of other patients. Later on I started hearing about all the research behind rewiring the brain. There are many exercises and techniques that help to do it, but the actual rewiring happens when you’re sleeping or at rest. And if you could go into a state of total not-knowing, with no thoughts, that’s the best environment for the brain to rewire. So now I think that because of the state of not-knowing that I was plunging into, I was able to rehabilitate faster.

You’re saying that your Zen training led to a faster rehabilitation? Yes. Of course, I should also say that we don’t want to recommend having a stroke just so you can plunge that deeply. [Laughs.]

You’ve also been an incredibly active teacher and manager for 60 years. Has your appreciation of interdependence changed in any way now that you are more reliant on others, and on the receiving end of so much support? [Pauses.] It’s taking me some time to answer, because it’s such an important question. Before the stroke I was very active. I went very fast, building all kinds of things. So I was very focused on doing, and in regard to other people, if they couldn’t do things with me, I didn’t deal with them.

The stroke changed me into someone who is now more concerned with compassion and feelings. I get sad now. I didn’t get sad before.

Really? Very little. I was much more concentrated on doing, and sadness didn’t fit. Now it’s completely different. It does fit. I see now as a new era, because after 78 years of operating out of doing, I’ve started to operate more out of compassion. That’s exciting for me; I’m looking forward to exploring that.

You mentioned that sadness has been a new emotion for you. I’m sure other difficult ones have come up as well during this experience—frustration, self-pity? For a few days after the stroke I seemed unconscious to most people. But I had some thoughts, and during that time those thoughts were that I wanted to kill myself. I thought that I was a burden. But I couldn’t communicate and I couldn’t move. So I wanted to kill myself, but I didn’t see how I could accomplish that. [Laughs.]

After a few days, that changed. It seemed to me that if I really, really threw myself into rehab, I could change the situation. As far as I’m concerned, from that time on there was no frustration. There was no self-pity. A determination to exercise and get out of the situation was all I could think of. And that has lasted, except for one thing.

My wife reminded me the other day that there was a period where I went through a deep depression that was linked to the antidepressant pills the hospital gave me [which they often give to stroke patients to aid recovery]. I’ve never needed them in my life, so I went off them, and I went into a deep depression again where I felt suicidal. There was no feeling of “Why is this happening to me?” but there was a feeling that this was happening to me, and I didn’t want it to be happening. I went back on the pills, and it hasn’t happened again.

You’ve been trained as a clown; even the stroke announcement on your website is laced with jokes. What role has humor played in your recovery? I put a lot of value in humor, and I find it in weird places. For me, it’s very healthy.

Can you tell us a weird place where you found it in the recovery period?

Rami [Bernie’s assistant]: I have one. The first or second night after Bernie returned from recovery, he fell. It was ten or eleven on a Friday. Eve, his wife, called me as well as 911. It took me 20 minutes to arrive, and I didn’t know what had happened—I didn’t know if you were hurt or how badly or anything. When I finally got here, I found you and Eve just cracking up. You were bouncing jokes and impersonations back and forth. I couldn’t tell whether the tears you guys had were out of laughing or out of the shock, because it was a very shocking thing for you to fall for the first time.

But I do remember how tender it was to come and see this married couple definitely distraught, but laughing.

Bernie: I don’t remember that. Of course, I remember falling. We had a hospital table that was on wheels, and it slipped away. So I fell and she couldn’t get me up, and I couldn’t get me up either. It was a fucking mess, definitely the kind of situation that you could be upset over. And while I don’t remember what we were laughing about, I’m not surprised that we were. I mean, most situations that are terrible, I find humor in them. What can I tell you? I’m a little weird. [Laughs.]

Is that because of your Zen training as well? No, that’s because I’m a Brooklyn Jew. [Laughs.]

Any final thoughts about the stroke or your recovery? For a long time, I’ve had the opinion that everything’s opinions; there are no truths. In Buddhism, many people say that Shakyamuni Buddha had four major truths. I find that to be strange. I say that he had four major opinions, because there can’t be truths if you’re talking about Buddhism.

Everything changes. I’ve experienced that in a deeper way due to my stroke. There’s nothing solid. Nothing solid.

–Emma Varvaloucas, Executive Editor

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.