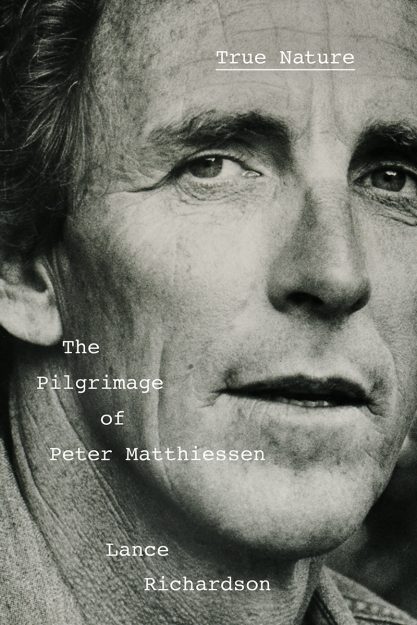

When author Lance Richardson approached Maria Matthiessen in 2017 with the idea of writing a book about her late husband, she told him he was committing to a subject that was far larger than he realized. Eight years and 736 pages later, I’m sure he agrees. But True Nature: The Pilgrimage of Peter Matthiessen is a magnificent literary biography, painstakingly researched, intricately organized, and beautifully written, fully worthy of its sensitive, restless, and driven subject, the only author to win the National Book Award in both fiction and nonfiction.

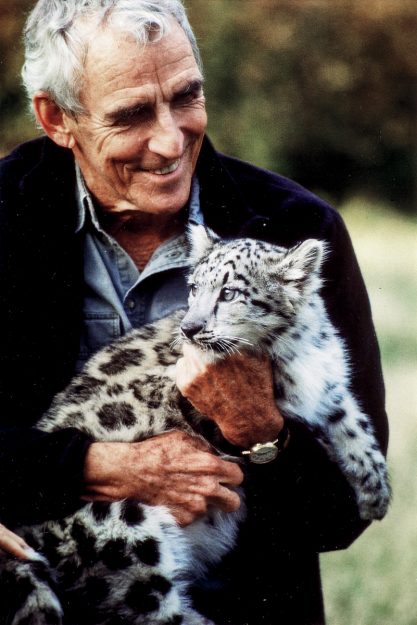

For members of my boomer generation, Matthiessen was a great nature writer and author of the iconic book The Snow Leopard. It was the story of a voyage to the East when the East had already begun to fascinate the counterculture generation, a journey that was both spiritual and physical, a quest that in one way did not succeed (he never saw the snow leopard) yet in another succeeded beautifully (as he mourned the death by cancer of his second wife). It synchronized perfectly with a cultural moment and became one of those books that everyone read.

Matthiessen, on the other hand, considered himself primarily a novelist. He came of age when the novel was king, when his famous contemporaries—many of whom were his friends—were writing massive blockbusters like Lie Down in Darkness and From Here to Eternity. In contrast, Matthiessen wrote offbeat novels like Far Tortuga, which didn’t get as much notice at the time but seem more interesting now. Matthiessen didn’t write his big novel, Shadow Country, until late in life, and, with it, he became not just a good but a great American novelist.

True Nature: The Pilgrimage of Peter Matthiessen

By Lance Richardson

Pantheon Books, 736 pp., $40.00, hardcover

Matthiessen was also a Zen priest who studied with Eido Roshi, Soen Roshi, and Taizan Maezumi Roshi, and received dharma transmission from Bernie Glassman. The Snow Leopard is full of information about Buddhism in general and Zen practice in particular. Matthiessen also published a book of journals about his Zen practice, Nine-Headed Dragon River, and at the end of his life wrote a Zen novel, In Paradise.

An undercurrent of spiritual seeking ran through his life, from his reading of Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows as a boy to an experience he had as a 19-year-old army recruit on a Naval vessel during a massive storm. “I lost my sense of self, the heartbeat I heard was the heartbeat of the world, I breathed with the mighty risings and decline of the earth, and this evanescence seemed less frightening than exalting.” He also did the Gurdjieff work when he was in Paris on his junior year abroad from Yale, and later, in the sixties, tried ayahuasca and used LSD several times.

Matthiessen became a nature writer (which Richardson amends to environmental writer) because his first two novels didn’t sell. He had always loved and reveled in nature, but his forays into it—even the numerous expeditions of his later years—were not aimless. “I’ve always had a longing for the primeval place, a primordial yearning for the lost paradise,” he said. But as Richardson points out, “Paradise was a state of being . . . to experience the world once more as a young child does: directly, immediately, without the burden of identity.” Indeed, if there was a shortcoming to his spiritual questing, it was that yearning for a special experience, to see the snow leopard, find Bigfoot (an odd obsession of his later years), and, in Zen, to experience kensho, the initial experience of insight into one’s true nature. That quest becomes tiresome in Nine-Headed Dragon River, but Matthiessen’s superb prose makes everything he writes interesting.

He had always loved and reveled in nature, but his forays into it—even the numerous expeditions of his later years—were not aimless.

There is another side to the questioning, and as much as Richardson admires Matthiessen—I do too—he doesn’t neglect it. Many teachings remind us that the paradise we’re seeking is right where we are, but Matthiessen was still obsessively heading off on expeditions into his 80s. Deep practice can help us see all experiences in meditation as important, not just a kensho that never seems to show up the way we expect. And human maturity sees that family life is as rich a place to practice as any monastery, if that is the path you choose. Matthiessen nominally chose family life, but he didn’t really live it.

His three marriages were to Patsy Southgate, with whom he had two children; to Deborah Love, with whom he had one child and adopted her daughter from a previous marriage; and finally to Maria Eckhart. All of the children resented Matthiessen for being neglectful and absent as a father, and for his volatile moods. The only child who got over his resentment was Alex, the 9-year-old whose mother had just died when Matthiessen went off in search of the snow leopard, but he reconciled with his father after the two men got together as adults and Alex laid out “the ways in which you were a shitty father.”

Fidelity was never one of his strengths. Though attractive to women all his life—“something terribly glamorous about such a loner,” one said—he developed a pattern in his relationships: Deborah Love, aware of his affairs, railed against them; he would apologize, promise to do better, then break those promises. The same dynamic played out with Eckhart.

Love’s death, nevertheless, shook Matthiessen deeply. He had begun his Zen practice with her but got earnest after she died, in the twenty-two months before he left for the Himalayas. He went on monthly sesshins at Dai Bosatsu monastery, in upstate New York, with both Eido Shimano and Soen Roshi. For a time, he was much more emotionally vulnerable and less sure of who he was. Eido Shimano was most helpful around the time of Love’s death, and sent him off to the Himalayas with his blessing, advising him to “expect nothing.”

Starting in the early eighties, at his home in Sagaponack, New York, Matthiessen had a habit of sitting every morning before he began his day’s work, and after a while, some neighbors began to join him. By that time, Matthiessen had moved his allegiance to Taizan Maezumi, eventually becoming the student of one of Maezumi’s dharma heirs, Bernie Glassman. It was Glassman who ordained Matthiessen as a priest and later gave him dharma transmission. By that time, the group in Sagaponack had grown into a full-fledged sangha, and Matthiessen began to give talks and lead sesshins. He was never entirely comfortable in the role, but his students appreciated him. “He was so personable and warm,” one said. “There was none of the coldness of Zen you sometimes get in that lineage.”

Matthiessen was still obsessively heading off on expeditions into his 80s.

Matthiessen had a longtime interest in Native American spirituality because it seemed to have a great deal in common with Zen, and eventually he grew interested in Native American political movements. After years of writing about the environment, he had come to believe in advocacy journalism; he wrote a massive volume on Leonard Peltier and the American Indian Movement, In the Spirit of Crazy Horse. He asserted Peltier’s innocence in the murder of two FBI agents (for which Peltier was eventually convicted), was sued for $49 million for that, and ultimately won, but only after Viking Press spent $2 million on attorneys.

Amid the difficulty, Matthiessen threw himself into his last great project, a novel about Edgar Watson, a notorious outlaw and killer whom his father had mentioned while fishing in the Everglades when Matthiessen was a boy. In a way, this was his ultimate exploration of a character who had shown up repeatedly in his fiction, “the specter escaped from the dark attic of the mind.” He saw his challenge as “finding common ground with a sociopathic killer” and believed that “fully recognizing man’s true nature, including its potential for great evil, is our only hope.” The Everglades in Watson’s day was the raw and oppressive natural setting that Matthiessen had often written about. This final project brought together all of his skills.

He first published a trilogy about Watson but never overcame the flaw that the second novel was connective tissue and didn’t stand alone. He eventually returned to his original idea of publishing the material as one novel, Shadow Country. I thought it was a masterpiece, and Matthiessen was shocked and gratified when it won the National Book Award, finally giving his fiction the recognition he felt it deserved.

Matthiessen’s death was sad and difficult, for a man who had spent so much of his life in strenuous physical pursuits; he died of leukemia at 86, three days before his final novel, In Paradise, was published. He had gone years before on one of the Auschwitz retreats that Bernie Glassman led, and at first tried to write a memoir about it but finally decided that fiction was a better vehicle. One hundred forty people went on the retreat, facing a darkness of humanity beyond even that of a man like Edgar Watson.

On the first night, Rabbi Don Singer led the crowd in a soft rendition of “Oseh Shalom.” Matthiessen watched as people began to join hands with the smiling rabbi, and “to dance, like a hora, or like a childhood game of Ring Around the Rosie. A few walked out in protest, seeing the dance as sacrilegious, but many others were transported by a surge of inexplicable joy. . . .”

As Matthiessen later explained to his sangha, “At first I thought this exhilaration derived from the energy and goodwill of so many good-hearted people. . . .

Now, I think I am just beginning to understand that the exhilaration came from the apprehension of a truth.” That truth, Richardson tells us, “was beyond easy articulation; it was like trying to describe kensho. Yet Matthiessen believed he’d glimpsed something vital about human nature.”

There are people these days who won’t follow an artist’s work because he fails morally in some way, and we hold our Zen teachers to an even higher standard than our artists (even though they have flaws like the rest of us). I suppose some people will avoid a biography for the same reason, but in this case, that would be a huge mistake. Matthiessen was no saint, obviously, and a massive failure as a husband and father. But he did, as the expression goes, write like an angel, and he spent his life exploring the spiritual and moral questions that obsessed him. Richardson was right to give so full a portrait of the man, and has written a book that is itself worthy of awards. It should be of interest to anyone drawn to the search for our true nature and the deepest truths of the human heart.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.