Joanna Macy is an activist, scholar, practitioner, philosopher, and—always—a teacher. Initially inspired by her Christian social conscience, then by work in the civil rights movement, Macy ended up in India with the Peace Corps in the mid-sixties working with Tibetan refugees. Returning to the United States, she undertook her doctoral studies in religion at Syracuse University. When H.H. the Sixteenth Karmapa came to this country, Macy went to request a blessing for her scholastic work. “He grabbed my head like a football, and gave this long blessing, which must have been for Manjushri. I felt as though I’d gotten my head stuck in an electric socket. I couldn’t sleep for three weeks after that.”

In this opened state, Macy wandered into a class on General Systems Theory and ever since has integrated dharma and systems into her work. Systems theory, or “systems-cybernetics,” as it is sometimes called, arose from the life sciences in the thirties. The field deals with irreducible wholes: atoms, molecules, cells, organs, bodies, families, societies, ecosystems, and so on. It seeks to understand behavior of these systems in relationship to their environs. Still a young science, systems theory has had obvious and fruitful application in both the physical and social sciences. Gregory Bateson, one of its most famous proponents, said that cybernetics was “the biggest bite out of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge that mankind has taken in the last two thousand years.”

Joanna Macy continued her practical work over the years, cutting roads and digging latrines with the Buddhist-inspired Sarvodaya Movement in Sri Lanka, and launching, through her writings and workshops, the field of “Despair Work” for disillusioned activists and others. More properly known as “Despair and Empowerment,” this approach acknowledges despair and “burnout” as honorable, springing as they do from the interconnectedness of all being. Macy posits that if these feelings are not blocked or ignored or covered over, they can be a tremendous source of further energy.

Her most recent project is Nuclear Guardianship, a citizen effort that champions the need to keep a mindful watch on the weapons and toxins produced by a militarized society.

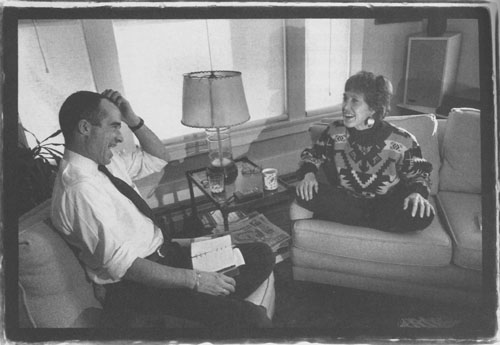

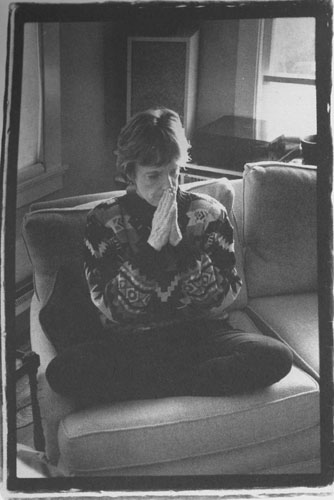

Macy is the author of Mutual Causality in Buddhism and General Systems Theory; Dharma and Development; and, with John Seed, Thinking Like a Mountain. Her latest book is World as Lover, World as Self, published by Parallax Press. This interview was conducted for Tricycle by Contributing Editor Tensho David Schneider. His biography of the late Zen teacher Issan Dorsey is forthcoming from Shambhala Publications this year. Photographs by Gaetano Kazuo Maida.

“Systems theory “—it sounds so dry. Did it strike you that way at the beginning? I remember spending a weekend at a little cottage with my family. My kids were in high school, and evenings we all did our homework. I would read a few lines of Ervin Laszlo’s Introduction to Systems Philosophy, and I would have to go outside and walk up and down, looking at the night sky and weeping. It was like whole-body knowing. It was like I already knew it. I thought about how lucky I am to be alive in a time when these elegant conceptualizations are available. Extraordinary tools to help us perceive the orderly patterning, the dynamic patterning of reality. In a way, it’s like being alive in a time when the dharma is taught. I was riveted. And images. All during that time, there were images of neurons and neural nets superimposed on Indra’s Net. I saw Indra’s Net being made up of neurons.

Let’s be reductive for a minute here about systems theory and dharma. Would you say that paticca samuppada—the theory of dependent co-arising—is a hinge between the two? The Buddha said he who sees the dharma sees paticca samuppada. He said other teachers can teach loving-kindness and generosity, but dependent co-arising is what buddhas and only buddhas teach. So it’s pretty central.

It’s a distinguishing mark, then, but as I understood it, it was a sort of bridge for you to the systems. There were a number of convergences that struck me right off the bat. One is that everything is in fluid, dynamic change all the time. Instead of separate, discrete entities, everything is flowing, interacting, and impinging on each other. We and the sun and the trees, all is perpetual flowing. It’s only the kind of senses we have that do this stop-photography. In actuality, everything is moving all the time, and it can be scary as hell.

There’s nowhere to rest. Right. There’s not even an experiencer alongside the flow of experience, which is a dizzying and powerful realization. That was one of the first things that I recognized in the systems vision. Unlike other philosophies, it doesn’t posit something outside of this rush of change. What the systems theorists seek to determine are the patterns and regularities they call invariances, in how things change. That’s what the Buddha was trying to figure out, too. The dharma is not about the essence of things so much as it’s about the way things work. You see, I was looking at it through Buddhist spectacles. In systems, the boundaries between organism and environment are very fluid. I found remarkable statements by system thinkers that were as resonant with no-self as any scripture.

Those two convergences are pretty convincing right there. Right. Like the Buddha, systems theorists are trying to figure out not the why, and not the what, but the how of things. That is the very meaning of dharma: how things happen. And, like the Buddha, systems theory shows that things arise and change through reciprocal interaction. In other words, nonlinear causality. That perception—of mutual causality—brings Buddhism and systems theory closer to each other than to any other school of thought. When I saw this, it was like an invitation to dance that I could not refuse. Another thing. I was struck right away that there was mind throughout.

Mind—as in consciousness—in both teachings? When I got to know the systems philosopher Laszlo—he took part in my dissertation committee, and I worked with him on a couple of projects—he asked me to write a one-sentence statement on his work for an exhibit. I wrote that his work demonstrates that mind is endemic in nature. You can’t reduce mind to what’s between our ears.

Systems theory makes the amazing assertion that nature is self-organizing. You don’t need mind, either divine or human, operating from above to make nature behave itself. The whole show is spontaneously self-regulating and self-evolving. Its very dynamics move toward complexity and intelligence. It is alive with mind. Laszlo suggests that mind is the interiority, or subjective dimension of every system. And matter, or physicality, is its externally observed dimension. These two dimensions are like the inside and outside of a house. You can neither separate them nor reduce one to the other. This is the most elegant resolution of the mind-matter problem I know. (Of course, the subjectivity of an atom is very rudimentary compared to our own, because the numbers of neurons and synaptic connections in our brains are trillions of times more complex than an atom.) But as in Buddhism too, consciousness is there throughout. I got very excited when I saw how the dynamics of self-organizing systems could explain why Buddhists teach that choice becomes possible in the human realm.

With self-reflection in humans? Yes. Buddhists say that among the six realms of existence, the distinctive feature of the human realm is that we can change our karma. Not even the gods can do that. Systems theory helps you see that self-reflexivity is just that: choice. The need to make a decision comes when you have a highly integrated and highly differentiated system, like the human brain. The alternatives are so plentiful, so rich in possibility, that in order to keep track of all the options, consciousness needs to jump up another level—in order to say, for example, “Do I finish this paper or go downtown?” or “Where did I put my keys?” That very process shunts us to a new perspective. Because it’s a step back from the concrete, it can also make us feel lonely and separate from other things.

You mean to handle all the information that comes from that integration? Consciousness is actually a continuous choicemaking process. As I often tell students at the outset of a course, among the many reasons that I teach is so that they can experience thinking as erotic. Not neurotic, erotic. We can’t afford to let rot any of this God-given or dharma-given intellect.

In my first excited reading of von Bertalanffy—the Austrian biologist generally regarded as the “father” of systems-cybernetics—bells went off and lights flashed, as I saw that here was an elegantly simple understanding of karma. By karma, I don’t mean reincarnation, but how we come to embody the fruits of our actions, how our actions matter.

And how was that? What shapes a system is its action. Just like the heart pumping. Von Bertalanffy says structure is the record of past function. Function is the source of future structures.

That’s karma, right there. Isn’t that gorgeous? So moral values are built into the nature of the universe. It’s the way things are. It’s not that there’s some big daddy god telling us how we should behave. But if we want to be conscious, or joyful, then there are certain ways we have to be.

To go along with it. Right, to participate in the dance.

Say you have a complicated, integrated computer system, taking in lots of data all the time. Would the systems view be then that that would also need this extra loop as you described it? And then is that conscious? Is that self-reflective? I don’t know. If a computer can change its karma, then it becomes conscious. That would be the test.

It’s clear that you found a lot of inspiration for your social action from your Buddhist practices and understanding. Do you also find inspiration in the systems work? Oh yes. I insisted on it.

What do you mean? Systems helped me see in fresh ways how a bodhisattva managed to be a bodhisattva. The prajna (wisdom) texts say that the bodhisattva has no place to stand. The bodhisattva flies on wings ofprajna and upaya (skillful means) and flies in the deep space of the great mother wisdom, and there’s no place to stand. With the systems perspective, I could say, “Of course.”

Because of that whole flow. Yes. Because it’s like we are nodes in the Net of Indra or neurons in the neural net, and all is happening through us. The loving happens through me. I don’t have to dredge up, out of my meager supply, enough caring and enough compassion and enough smarts to do it. I don’t need to.

You don’t have to own it. No. It’s there, it’s inherent in the web already.

Therefore action would be obvious. It wouldn’t be something you had to strategize. And that’s important because it relieves you of having to know everything, of having to have a blueprint. I think you don’t have to have a solution before you do anything. It’s like grace. It’s close to the Christian concept of grace, where the divine works through you, except that here, the power that flows through is the interdependence of all things, channeled through your choice-making. I remember thinking, Oh, the bodhisattva is a transformer. Intention becomes very powerful because you’re choosing what to do with the river, the current of energy and information. It’s what you do with it.

How you direct it. Right. Interestingly enough, systems theory emerged in the same decade that we split the atom. It came out of the life sciences: there were too many anomalies. Among them was the fact that life evolved into more and more complex forms. The fact that complexity and intelligence arise is a rather large exception to the Second Law of Thermodynamics, where everything is seen to run down. To understand this, von Bertalanffy looked at the interactive way biological systems adapt and repair and sustain themselves. The self-organizing properties he detected were soon observed in cognitive systems as well and were understood in terms of feedback. Feedback, the adjustment of output in terms of input, or behavior in terms of experience, generates form and intelligence.

That happens in feedback loops? Yes, that’s how nature self-organizes. Because living systems or wholes are in continual interaction. Feedback is just another term for this kind of conversation that’s going on all the time. A conversation between my lungs and the leaves of the tree. To act as if you’re separate from this circuitry is highly dysfunctional, because you’re actually an integral part of a larger system.

But you set yourself apart. Yes. You mislead yourself about this. Deception breaks the feedback loops. Systems require truth-telling to function well. Once you start lying, they begin to break down. There are certain natural precepts. Generosity is essential to life. All of life is a generosity. If you get nervous, thinking you’d better nail down who you are, and this is mine and this is mine, then the dance jams up.

Suppose you’re feeling tired and despairing, from having attempted social action, and you happen to run into this idea that nature is self-organizing. It would be a temptation to say “OK, all these problems we’re having, all this foolishness that human beings seem to be engaged in is part of some bigger organization, a bigger system that I don’t necessarily see. Why should I fight so hard?” People say the same thing about Buddha’s teachings, especially Mahayana. “If in the final analysis there are no separate beings for the bodhisattva to lead to nirvana…”

Why bother? He doesn’t really exist, and they don’t really exist and the path doesn’t really exist. . . So the answer to “Why bother?” is something of a mystery. But when a person says he feels no need to bother, and wi1llet things take their course, I don’t really believe it. I don’t believe it because, honey, you are built to survive. If I were to hold your head under water, you wouldn’t just say, “I guess she’s holding my head under water.” You’d come up with the strength of one hundred men. Sometimes I hear people say our species is so messed up it’s better we just bow out now and leave the scene. But I don’t think that’s dispassionate higher wisdom so much as denial of what they feel and what they are.

Of their real nature you mean? Yes, and of their pain, and of their hope for our world, which is such a mess. In system terms, expectations are the programs or codes around which a system self-organizes. In order to change, and let new responses or new life emerge, systems reorganize—the old codes break down. I like the term positive disintegration. We’ve done this countless times in our five billion years here. We have reorganized all the way along, by receiving and responding to feedback about what’s going on. Sometimes it can be pretty uncomfortable. Imagine when oxygen first came in, or when we were pushing around on our fins trying to find some water. We have to absolutely be open to feedback.

Aren’t we? No, the great danger now is that we block so much feedback, both through official secrecy and through psychological denial. We feel that the crisis is too big to let in. That’s why a major part of my work in the last fifteen years has been the despair work, to help us stop blocking feedback.

In this respect, television, as it functions in our culture, discourages me about our chances to pull through. We have evolved this incredible mental and sensory equipment—the brain, the most complex object in the known universe—and we turn it into jelly as we sit there, zonking out.

Because of the extraordinary circumstances we are confronting now, at this juncture of history, there’s a chance for wholesale transformation. Clarity and firmness of intention can have much more effect than in more stable times.

Because it’s all up for grabs now, in a way? Or about to be? Up until now we have managed by way of certain social technologies, like the ballot box. It is possible that collective consciousness could arise, because the ability to make rapid collective decisions is necessary for our survival. This pressure comes from the self-organizing nature of life itself. I’m not sure how it’s going to happen. Communication helps, but the shift to collective consensus, when it happens, will be felt by each of us. It’s like we are separate neurons in a larger brain, and we’re beginning to discover that the brain is starting to think, that we’re being thought through. This hardly means that we’ll lose our individuality, because systems demonstrates that the more integrated you are, the more differentiated you become.

Let me take that theme then, for a moment, down onto a very mundane plane. In terms of real social action, do you think there is a place for a distinctly Buddhist approach? Or should we join in with the Christians, who’ve been doing this pretty well for about one thousand years? Both. But I have no rational answer. My answer would have to do with things like weight and color and texture. I love dharma and feel so lucky to be born in a time and place where I can connect with it. It’s nice to hang around with people who feel the same way. But I don’t like saying that it’s because we Buddhists do things better. It just feels lighter to me, the way Buddhists go about social action. There’s an outrageousness about Buddhists. They’re willing to let the answer reveal itself. The path reveals itself, so you really don’t know what’s coming.

From World as Lover, World as Self:

The way we define and delimit the self is arbitrary. We can place it between our ears and have it looking out from our eyes, or we can widen it to include the air we breathe, or at other moments we can cast its boundaries farther to include the oxygen-giving trees and plankton, our external lungs, and beyond them the web of life in which they are sustained.

I used to think that I ended with my skin, that everything within the skin was me and everything outside the skin was not. But now you’ve read these words, and the concepts they represent are reaching your cortex, so “the process” that is me now extends as far as you. And where, for that matter, did this process begin? I certainly can trace it to my teachers, some of whom I never met, and to my husband and children, who give me courage and support to do the work I do, and to the plant and animal beings who sustain my body. What I am, as systems theorists have helped me see, is a “flow-through.” I am a flow-through of matter, energy, and information, which is transformed in turn by my own experiences and intentions. Systems theory seeks to define the principles by which this transformation occurs, but not the stuff itself that flows through, for that, in the last analysis, would be a metaphysical endeavor. Systems thinkers Kenneth and Elise Boulding suggest that we could simply call it agape—the Greek and early-Christian word for “love.”

This interdependent release of fresh potential is called synergy. It is like grace, because it brings an increase of power beyond one’s own capacity as a separate entity. I see the operation of this kind of grace or synergy everywhere I go. For example, I see it in the network of citizens that has sprung up along the tracks of the “white train” that carries the nuclear warheads from the Pantex plant in Amarillo, Texas, up to the Trident base in the Northwest on Puget Sound and across the South to the Charleston Naval Base on the Atlantic. Sitting up late at night to watch the tracks, they telephone to alert each other that the train is coming their way; then these ordinary citizens come out of their homes, to stand by the railroad line and vigil with lighted candles or, on occasion, put their bodies on the tracks to stop the train. Even though this network is scattered across thousands of miles and relatively few of its members have met face to face, it calls itself now the Agape community; for these people have learned to feel each other’s presence and support. And the tracks that bear the weapons for the ultimate war have become arteries interconnecting people and eliciting new dimensions of caring and courage.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.