As American Buddhists contemplate the present political moment, we may experience considerable confusion about what—if anything—we should do to make a difference. Isn’t the real work of Buddhists the individual inner work of rooting out the defilements (the kilesas) that impede our spiritual awakening? In 1992, while staying at a Thai forest monastery, I was told this by an eminent Western monk, who suggested that social work may help, but shouldn’t be confused with the heart of Buddhist practice.

This view, which I have also heard from Mahayana teachers, has a basis in Buddhist tradition. The central focus of the Buddha’s teachings was on individual transformation for monastics. A clear boundary separated the monastery and “politics,” which was understood (in a way very different from Western notions of politics) as related to the activities of kings. “Danger from kings” was a greater concern than danger from robbers, fire, or wild animals.

On the other hand, contemporary socially engaged Buddhists—such as Vietnamese Zen teacher Thich Nhat Hanh, the Dalai Lama, activist Joanna Macy, and Burmese dissident Aung San Suu Kyi—advocate connecting individual practice with a response to social conditions. “Mindfulness must be engaged. Once there is seeing, there must be acting,” writes Thich Nhat Hanh in Peace Is Every Step. “We must be aware of the real problems of the world. Then, with mindfulness, we will know what to do and what not to do to be of help.”

This view also can find support in Buddhist tradition. The Buddha sometimes expressed concerns about cultivating the conditions for social harmony, and intervened several times to prevent wars. The five ethical precepts—which urge us to refrain from killing, stealing, lying, sexual misconduct, and the harmful use of intoxicants —have often been interpreted as guidelines for society. The great Indian king Ashoka gave edicts based on the precepts—laws that stipulated the protection of animals and the elimination of the death penalty. The Mahayana movement popularized the inspiring figure of the bodhisattva, dedicated to the awakening both of self and of others.

But even if we want to be engaged, we face further challenges. What should be our guidelines, given that the Buddha gave relatively few social teachings, and that the contemporary world is very different from the agrarian world of the Buddha? How do we participate as Buddhists in contexts that are guided by secular assumptions, including the separation of church and state?

Should Buddhists endorse policies and political candidates? Does that cross a line, enmeshing us in squabbles, full of unwise speech and attachments to views and power? In Being Peace, Thich Nhat Hanh maintains that “a religious community should take a clear stand against oppression and injustice, and should strive to change the situation without engaging in partisan conflicts.” But how do we take a clear stand without sometimes being partisan? And the “progressive” activists, who often so accurately identify social problems—well, they sometimes seem so angry, self-righteous, and prone to one-sided views—so . . . un-Buddhist! With whom can we act?

These are koans of our times. In what follows, I give five basic guidelines for Buddhist social and political action, which, while they may not give definitive answers, can orient our approaches to these questions.

1. As part of your commitment to practice, take moral and spiritual responsibility for the suffering of the world.

The core of Buddhist practice is the transformation of suffering (dukkha) and its roots into wisdom and compassion. As the Buddha pointed out, we all experience physical and emotional pain. We all get sick, lose people we love, and each of us will die.Our practice is not to try to get rid of this pain, which would be impossible. Rather, it is to avoid constricting around our pain, or blaming ourselves or others for it, or lashing out when we feel attacked—somehow believing that by so doing we will get rid of or resolve the initial hurt.

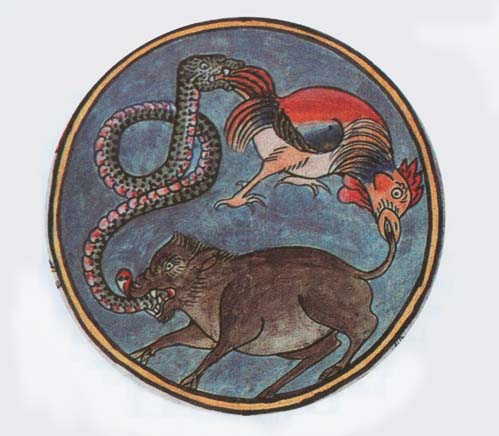

This cycle of reactivity is called suffering. The task of our practice is to transform such reactivity and the greed, hatred, and delusion that fuel it. It is to realize that it is possible to experience pain without suffering, without passing on the pain to ourselves or others.

Socially engaged Buddhists suggest that our commitment to this practice entails taking responsibility for all parts of our lives. We try to stop perpetuating these cycles of reactivity and violence not just in relation to ourselves but also in our interpersonal relationships, and in our role as citizens in a democratic society. The groundbreaking nonviolence of Gandhi and King was guided by the same intention—not to pass on the pain of oppression and racism by continuing the cycles of violence, and to bring compassion to those who are suffering. They echo the Buddha’s words: “Violence never ceases through hatred. It is only through love that it ceases. This is an ancient law.”

Our commitment to the ethical precepts can also give us a clear sense of our social responsibility, as well as safeguard our social and political involvement. Thich Nhat Hanh interprets the precepts as requiring our moral responsibility as Buddhist practitioners for the collective situation. His versions of the first and second precepts, in Being Peace, read: “Do not kill. Do not let others kill. Find whatever means possible to protect life and to prevent war. . . . Possess nothing that should belong to others. . . . Prevent others from enriching themselves from human suffering or the suffering of other beings.” We may be reminded how the Buddha in the Sutta Nipata originally formulated the social dimension of these precepts by guiding us neither to “cause others” to kill or steal nor to “approve of” them doing so.

2. Learn to see social and political phenomena through dharma eyes.

In mindfulness practice, we study our reactive tendencies. We study in depth, often more than we might like, our tendencies to be judgmental, or to overplan, or blame ourselves and/or others, or engage in endless inner dialogue about minor issues, or fixate on past or future events, or somaticize emotional difficulties. With extended stays in this “laboratory,” we can much more easily see similar tendencies manifest, somewhat more complexly, in our families, organizations, and communities, as well as in our social, economic, and political systems.

We can come to see the commonalities between events in the world and our minds, as Vipassana teacher Michele MacDonald suggests: “Today, reporting from Baghdad, my mind. A lot of sniping going on and an explosion on the edge of town.”

We can identify more clearly the “three poisons” of hatred, greed, and delusion around us—and in us. We can discern how the “war on terror,” and the jihad of Al Qaeda, like many conflicts, are in part expressions of vicious cycles of tit-for-tat, familiar from our personal experience. Enmeshed in collective hatred and anger, each side proclaims the crimes of the other and its own self-righteousness, is unable to listen to the other’s suffering and cannot look at the deeper roots of the conflict and how we must have enemies in order to maintain our rigid identities. We can also understand how our economic institutions are increasingly rooted in collective greed, which, as we know from our individual practices, stems from self-centeredness, the view that my desires are most important, a related lack of a sense of connection to others, and inattention to long-term consequences. Similarly, we can identify and clarify the structures of collective delusion, evident, for example, in the workings of the mass media, educational institutions, and our self-triumphant political ideologies, and rooted in our self-ignorance. As Shantideva suggests in A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life: “This entire world is disturbed with insanity / Due to the exertions of those who are confused about themselves.”

Going more deeply, we notice our “collective shadow” emerging from unresolved collective pain—such as from the near genocide of Native American peoples, the history of slavery and racism, or the violence connected with American foreign policy (since 1945, according to social scientist Johan Galtung, some 70 interventions and some 12 million to 16 million people killed, directly or indirectly). Our lack of awareness of this material manifests in collective denial (particularly of responsibility), projection, and further cycles of violence.

Seeing through dharma eyes also helps us to locate the rich, transformative resources embodied in American traditions—such as the (relative) freedom of information and expression; the great legacies of movements for social justice; the spiritual and creative gifts of those whom we have most oppressed, particularly those of Native American and African descent; the spiritual resources of democratic traditions articulated by Americans from the Founding Fathers through Walt Whitman and Rosa Parks; and the moral richness of longstanding practices of hard work, plain speech, openness, community, and grassroots activism.

3. Remember that you don’t have to do everything.

In conducting retreats that help to connect individual practice with action in the world, I often hear: (1) “I feel isolated”; (2) ‘I’m not doing enough”; and (3) “I don’t know what to do.” These perceptions and emotions can soon lead to burnout, despair, and withdrawal.

I have often responded by giving a model of three types of transformative action, developed by Joanna Macy. First, there are “holding actions” such as protests, political and legislative work, and civil disobedience; their aim is to prevent further harm. Second, there is an analysis of the structural roots of problems and the development of alternative institutions-such as in health and medicine, education, or economics. Third, there are practices, such as meditation, art, and immersion in wilderness, to name a few, that alter the way we experience and understand ourselves, others, and the world; our current moral, political, and ecological problems in many ways reflect a crisis of perception.

All three types of transformative action are very much needed. We might respond deeply to our present situation by developing an alternative school in our community. Or teaching yoga and a different way of experiencing our bodies. Or working full-time for an environmental organization. Or doing a long meditation retreat. When we ground whatever we’re doing in an understanding of transforming suffering and how the three forms of action are related, we can feel connected with others doing very different work.

My retreatants typically emit sighs of relief upon hearing of this model. We don’t have to do everything! We can be active in ways that express our callings and our gifts, and that respect our cycles of inner work and outer action.

Sometimes we need refuge and renewal, often for an extended period. There is also an important role in social transformation for contemplatives—’like the great Thai monk Buddhadasa (1906-1993), who received activists at his forest monastery, and wrote about spiritual responses to social ills.

4. In hard times, learn how to transform difficult emotions and tendencies to polarize.

As social activists we may become “burned out” by constantly being with people in pain. We may become confused and depressed when ten million demonstrators don’t stop the invasion of Iraq. We may be energized in our activism by deep bitterness and anger. Without transforming these often unconscious emotional reactions to the pain of our world, we often become paralyzed or reactive, incapable of wise action.

Joanna Macy and others have developed collective practices that help us to open to this pain for our world and to work through these emotions, guided by compassion and a deepening understanding of interdependence, and leading eventually toward renewal and action. In leading these group practices before and after the invasion of Iraq, I became further aware of the great weight we normally carry. I also witnessed how healing and trans formative it is to touch our pain for the world within a safe environment, how intermingled such pain is with our personal pain, and how important such work is for compassionate action.

It’s also important to shift our usual adversarial attitude toward our “enemies,” whether George Bush, Osama bin Laden, coworkers, or members of our sanghas. Of great value are traditional practices such as the brahmaviharas (the development of positive mind states), particularly lovingkindness and compassion practices; tonglen (the Tibetan practice of giving and receiving); as well as the cultivation of mindfulness. These practices are particularly important when we take stands or enter territory conducive to partisan conflicts. We come to see better the extent to which we form a kind of system with our enemy, each projecting the negative onto the other. Yet we can take the appearance of an enemy as an invitation to practice, remembering Shantideva: “I should be happy to have an enemy / For

he assists me in my conduct of awakening.”

5. Prepare for the long haul—and for immediate insight and transformation.

Although it is crucial for many to be active in the 2004 elections, we also need a long-term perspective. To get at the deeper roots of collective problems requires our being here for the long haul.

The qualities necessary for the long haul are the virtues of the bodhisattva: patience, equanimity, wisdom, and skillful means (upaya), among others. These qualities help us to stay balanced while remaining socially engaged. In the face of ongoing challenges, we need both determination and spaciousness, courage and lightness, opening to both suffering and joy-exactly the qualities that seem present in the Dalai Lama’s laugh, even as he lives with the horrors of the Chinese occupation.

As in individual dharma practice, we both prepare for the long haul and remain open to immediate insight and change. As we know from considering the end of apartheid in South Africa and the breakup of the Soviet Union, change sometimes comes unexpectedly and swiftly, for better or for worse. A number of variables of our larger systems-particularly economic and ecological ones-as well as some crucial events (like the attacks of September 11) are highly unpredictable.

The perspectives of both gradual and sudden transformation may remind us that, as the Buddha taught, every moment of mindfulness matters! When we are mindful of the nearby trees or respond skillfully to a sarcastic word from a coworker, we are “stopping the war.” The success of action may be measured, as Thich Nhah Hanh suggests in Love in Action, less by outer victory than by whether love and nonviolence have been furthered. And we may remember the words of the second-century teacher Rabbi Tarfon: “It is not upon you to finish the work. Neither are you free to desist from it.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.