I remember a three-month training period at Zen Mountain Center, when I was the chiden, the caretaker of altars and offerings. It was during the summer months, when the shaded gully of the San Jacinto mountains holds the heat of the surrounding Southern California desert. During a very formal memorial service, as I was carrying a tray of elegant, lacquered wooden offering cups between the Meditation Hall and the Buddha Hall, one of them toppled over. It bounced off the surface of the zendo deck onto some rocks. Scrambling after it, I saw that a chip was missing, exposing the red wood beneath like an angry scar, gashing the polished surface. I was devastated and desperately wanted to repair it, to replace it, to make good the damage done. I decided to order a new one from Japan and that evening in the dokusan room, I told this to Maezumi Roshi. He said, “Why! With the chip it is more valuable. See, just as it is.”

As the years pass after Maezumi Roshi’s death, this emerges as his great teaching for me. A cup is more valuable chipped. He was broken. I am broken. And when we can see that we are all chipped and broken, we begin to value our life as an expression of the teaching that we are truly perfect and complete, just as we are.

For many of us, schooled in a dualistic way of thinking, good is good and bad is bad. Like oil and water, they don’t mix. We are taught that we are born with original sin that predisposes us to evil but that by exercising our willpower we can do something about it. So right from the beginning there is this sense of deficiency and unworthiness, and we undertake spiritual practice as a course in self-improvement, hoping that by being a better person, we will be worthier of love.

But the Buddha’s teachings say that we are perfect and complete just as we are—chipped and broken. And this was a teaching Roshi knew intimately.

That Maezumi Roshi liked to drink was no secret. But around 1984, members of the Zen Center of Los Angeles confronted Roshi about his excessive drinking and about behavioral patterns associated with alcoholic addiction. Reaction in the sangha varied considerably; some denied any problem at all, whereas others left the Center utterly disillusioned. Some people argued that his drinking was his problem and had no effect on his teaching, and that enlightened mind could not be assessed in the same way as conventional mind. Still others acknowledged their responsibility in letting things go for so long, and sought to engage themselves in a process of learning from the experience and of investigating how a teacher and a community heal themselves. I was studying in New York at that time. Yet I closely followed reports of his response to his sangha, his ultimate willingness to enter a treatment center, to learn about addiction, and his subsequent return to his community. This was followed by years of publicly owning responsibility for problems that his drinking had caused, and engaging the sangha in dialogue and atonement.

All of this I saw from the other side of the continent, and as an adult child of alcoholics and a former substance abuser myself, I watched with more than just passing interest. Now I realize that I may have been drawn to study with Roshi for this very reason. It was as if his struggle gave me permission to turn and face my own scars, to embrace and make peace with that part of me that had once spiraled out of control too, that had been broken beyond repair. I wanted to study with a dharma teacher who had experienced the seductive and haunting quality of addiction, to study with someone whose life was dedicated to the dharma and who was also affected by the ravages of alcohol. I wanted to amplify my understanding of how the dharma works with an overt instance of human suffering—of how it deals with brokenness.

I was interested, to put it bluntly, in someone who was actively dealing with craving. And who didn’t hide it. I wasn’t interested in a perfect teacher. I don’t think there is such a thing as a perfect teacher. Being human is not about being perfect; it is about being human. And that means being brokenhearted. Sitting with me knee to knee in dokusan, intimate with himself, present to his own suffering, he would exhort me to do likewise: “Appreciate your life, Enkyo,” he would say.

Now, as I sit in the dokusan room, listening to a sexual compulsive struggle with his addiction, or a young woman agonizing over her eating disorder, I can hear Roshi saying, “Appreciate your life!” Our very life itself is the Buddha Way. There’s no gap between our life and our practice.

Once I was working on a koan about a Zen teacher who would personally bring out the rice pail at lunchtime and dance and laugh, saying, “Come, bodhisattvas, come and eat your meal!” It’s a very straightforward koan. And I gave my presentation, my understanding of it, and he approved. I was sitting there feeling very satisfied with myself, and he said, “ENKYO!” with a very fierce expression on his face. Slowly, emphatically, the words came out: “He had tears in his eyes to teach them because they did not see.”

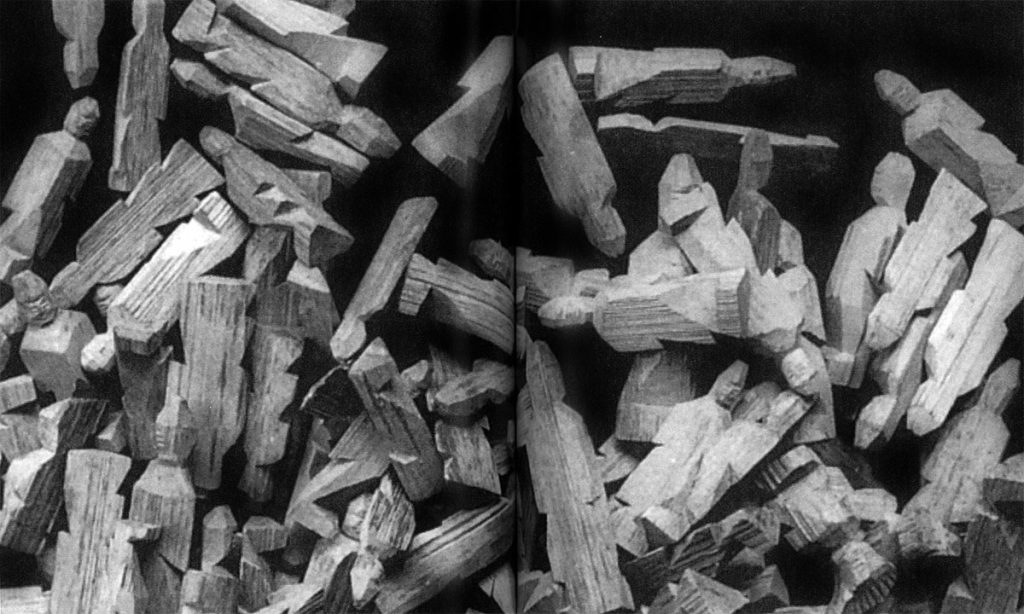

And that was Roshi. All his life he had tears in his eyes to teach us because we could not see. With tears in his eyes, with a tiny little body, afflicted with suffering, gashed and chipped. This was his teaching.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.