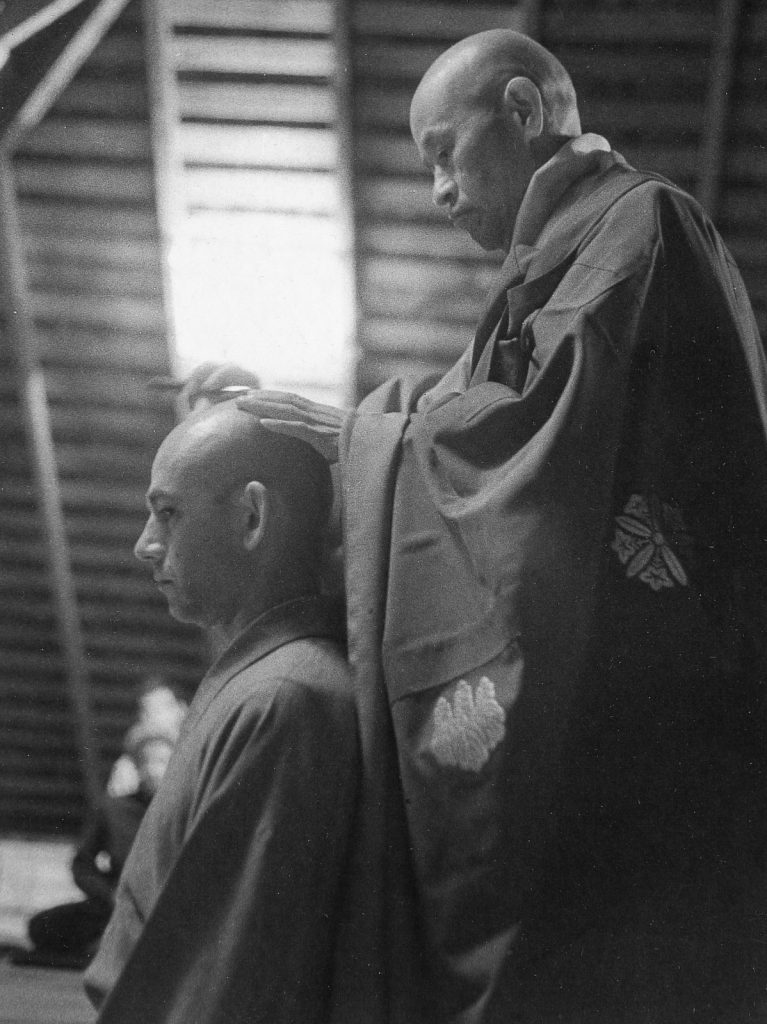

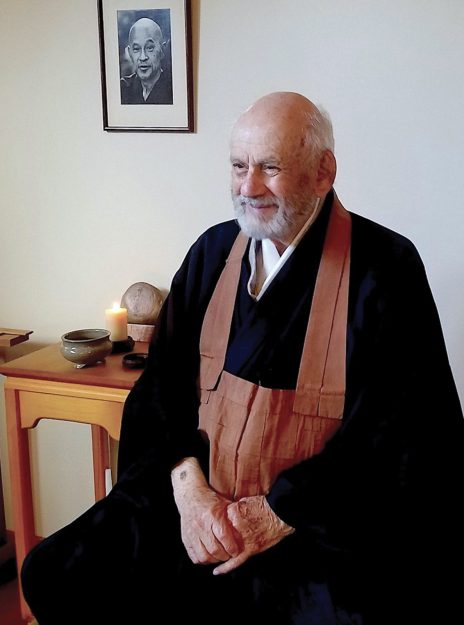

Alive or dead? In conventional terms, my teacher, Sojun Mel Weitsman Roshi, died on January 7, 2021, at home in Berkeley, California. For 53 years, he cultivated the empty field of zazen (seated meditation) at Berkeley Zen Center. More than thirty of his disciples received transmission, and hundreds of students loved him. We treasured Sojun’s warm, ordinary way—“nothing special,” just his unswerving commitment to zazen and community, learned from his teacher Shunryu Suzuki Roshi.

Alive or dead? This is the pivotal question in a well-known Zen koan—“Daowu’s Condolence Call,” case 55 in the classic 12th-century collection known as The Blue Cliff Record. Sojun Roshi reflected on this koan at a moment when his illness was visible to all. So he had offered to speak about birth and death to his students. This excerpt is from a talk given for the BZC “online zendo” on Saturday, November 7, 2020, two months to the day before his death. Sojun Roshi’s voice was clear and strong, his laughter bubbling to the surface, as he spoke to his students and answered their questions.

Regarding my teacher, Sojun Mel Weitsman, if I were asked, “Alive or dead?” I would stamp my foot three times and shout, “Alive! Alive!”

—Hozan Alan Senauke

Students often ask a Zen teacher “What is the most important thing?” Responses to that question depend on the moment and circumstances. Master Dogen, Shakyamuni Buddha, and all Zen and Buddhist notables say the most important thing is the problem of birth and death. We can never fully understand birth and death, but we make an effort because it’s the most important thing. When we are born, the most important thing is to just be born. When it’s time to die, the most important thing is just to die.

There is a koan in The Blue Cliff Record‚ “Daowu’s Condolence Call.” I call this an “old warhorse.” We drag out the old war horse and mount up again. We actually can’t discuss it too many times, because it may be our most important koan. Here is the main subject. [Editor’s note: The koan text is adapted from Thomas Cleary’s translation.]

Daowu and his disciple Jianyuan went to a house to make a condolence call.

This is in the 8th century, by the way. In order to express sympathy in those days, Zen monks did not do funeral services. They just went to visit the family to acknowledge the deceased.

Jianyuan hit the coffin and said, “Alive or dead?”

Jianyuan brought up the great question.

Daowu said, “I won’t say alive, and I won’t say dead.”

Jianyuan said, “Why won’t you say?”

Daowu said, “I won’t say.”

Halfway back, as they were returning, Jianyuan said, “Tell me right away, Teacher; if you don’t tell me, I’ll hit you.”

Daowu said, “ You may hit me, but I won’t say.” So Jianyuan hit him.

In time, Daowu died, and Jianyuan went to study with Master Shishuang. He told Shishuang about his exchange with Daowu and asked about his point of view.

Shishuang said, “I won’t say alive, and I won’t say dead.”

Jianyuan said, “Why won’t you say?”

Shishuang just said, “I won’t say, I won’t say.”

At these words Jianyuan had an insight.

Later, Jianyuan, carrying a hoe, went up and down in the lecture hall as if he were searching for something. Shishuang said, “What are you doing?”

Jianyuan said, “I’m searching for the spiritual remains of our dead teacher.”

Shishuang said, “Limitless expanse of mighty roaring waves; foaming waves wash the sky. What relic of the deceased teacher do you seek?

Now, here is the verse of Xuedou, the compiler of the record:

Hares and horses have horns. Cows and goats don’t have any. It is quite infinitesimal. It piles up mountain high. The golden relic exists; it still exists now. Foaming waves wash the sky. Where can you put it? No, nowhere. The single sandal returned to India and is lost forever.

So why would Daowu refuse to say anything about it to Jianyuan?

QUESTIONS & ANSWERS

STUDENT 1: It strikes me that Jianyuan only achieves enlightenment by asking a question again and again, to which he receives no answer. What does it mean to ask questions that our teachers will never answer for us, and how do we practice in this way?

SOJUN MEL WEITSMAN ROSHI (SMWR): The question bounces off the teacher back to you. You ask the question, and then it’s your turn to answer the question. The teacher only gives you certain hints or keys. “Answer” may not be the right word, but you’re supposed to answer somehow. If I tell you what the answer is, I would do you a great disservice by depriving you of working on your koan.

“Every moment is a moment of birth. Every moment is a moment of death. Birth and death are the two dynamics of life. Life itself doesn’t change.”

The key thing is, why won’t the teacher say? What is he withholding? The teacher is saying it’s your problem. Each one of us has to deal with this problem by ourself. Otherwise, it’s not our true understanding.

I want to say something about birth and death. I don’t use the term “life and death.” I use the term “birth and death.”

Birth and death are two sides of the coin of life. Within birth there is death. Within death there is birth. It can’t be just one way. So every moment is a moment of birth. Every moment is a moment of death. Birth and death are the two dynamics of life. Life itself is still. Life doesn’t change.

***

STUDENT 2: Of course, I did have that reaction—why won’t he say? I think there is an answer. But I’m trying to understand that there is no answer.

SMWR: There is an answer.

STUDENT 2: OK, what’s the answer?

SMWR: You tell me.

STUDENT 2: I think one of your main teachings is always to look at the

other side of things. So when we find ourselves falling into duality, to remind ourselves to look at the other side. It’s all one thing. I was thinking of it as an avenue between the two things, but in fact it’s the whole thing.

SMWR: Differentiation is important. Unity is important. It’s the unity of differentiation and differentiation of unity, which is what life is about.That’s not just about what we want. It’s not just about what we like. It’s not just about our fantasies. Our fantasies are truly seeing the world upside down.

In the new paradigm it appears that lies are truth. Lies are truth, and half of the country believes it. Our practice is to stabilize our mind and not let it get turned upside down.

***

STUDENT 3: The teacher is within the student; the student is within the teacher. But the student still has to polish the teacher’s relics.

SMWR: That’s an interesting statement. Is that a statement or a question?

STUDENT 3: I don’t know.That’s my understanding.

SMWR: If they have a real relationship, yes. At the same time, the teacher is always the teacher; the student is always the student. So tell me, what do you think the relics of the teacher in the student are?

STUDENT 3: Nothing. No difference.

SMWR: OK, well, I’ll give you a response. There is a difference, and there is no difference. Just saying “no difference” is a dualistic statement. So yes, there is no difference, and yes, there are many differences. Those two together make a complete statement of truth.

You and I are one, and you and I are many. Our true relationship is with the cosmos as well as here on Earth. I’m not trying to sound mysterious. That’s the way it is. We both belong to the cosmos. Our teacher is Shakyamuni Buddha. I’m your provisional teacher. We always have to remember that. So you may point to me, and I point to Shakyamuni.

“You and I are one, and you and I are many. Our relationship is with the cosmos as well as here on Earth. I’m not trying to sound mysterious. That’s the way it is.”

***

STUDENT 4: You said earlier that life is still, completely still. From that, I inferred that birth and death are activities.

SMWR: The activities of stillness.

STUDENT 4: The first precept says “Do not kill.”What does that mean if birth and death are activities of life?

SMWR: Don’t kill life. When you say “Don’t kill,” that’s not pointing to anything. It needs a subject—don’t kill what? Not killing is a koan, the first precept. All the precepts are actually koans. They all consider the impossible. There’s no way that we can kill anything. And we’re killing everything all the time. Everything is eating everything. The big fish eat the little fish, and so on. We transform life. Whales take in an enormous amount of krill, a tiny shrimp-like animal.

STUDENT 4: It sounds like the whale cannot kill krill.

SMWR: That’s right.

STUDENT 4: That’s a thrill.

SMWR: The whale gets a thrill from krill. [Laughs.] The whale cannot kill krill. Because nothing dies. There’s only transformation. Life is always transforming life. And life transforms life in various ways, through fires, freezes, and meltdowns. All this change—which we may or may not accept, like, or want—is reality.

That’s why Daowu said, “I won’t say. I won’t say.”

***

STUDENT 5: How does “not one, not two” fit into this koan?

SMWR: Does it?

STUDENT 5: I think it does.

SMWR: Don’t get stuck on anything, as my old teacher always said.

Don’t get hung up on oneness, and don’t get hung up on duality. Not one, not two.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.