When we take the one seat on our meditation cushion we become our own monastery. We create the compassionate space that allows for the arising of all things: sorrows, loneliness, shame, desire, regret, frustration, happiness.

Spiritual transformation is a profound process that doesn’t happen by accident. We need a repeated discipline, a genuine training, in order to let go of our old habits of mind and to find and sustain a new way of seeing. To mature on the spiritual path we need to commit ourselves in a systematic way. My teacher Achaan Chah described this commitment as “taking the one seat.” He said, “Just go into the room and put one chair in the center. Take the seat in the center of the room, open the doors and the windows, and see who comes to visit. You will witness all kinds of scenes and actors, all kinds of temptations and stories, everything imaginable. Your only job is to stay in your seat. You will see it all arise and pass, and out of this, wisdom and understanding will come.”

Achaan Chah’s description is both literal and metaphorical, and his image of taking the one seat describes two related aspects of spiritual work. Outwardly, it means selecting one practice and teacher among all of the possibilities, and inwardly, it means having the determination to stick with that practice through whatever difficulties and doubts arise until you have come to true clarity and understanding.

Every great spiritual tradition in every culture and in every age offers vehicles for awakening. These include body disciplines, prayer, meditation, selfless service, certain forms of modern therapy, and a variety of ceremonial and devotional practices. All of these are used as means to ripen us, to bring us face to face again and again with our life, and to help us to see in a new way by developing a stillness of mind and strength of heart. Undertaking any of these practices requires a deep commitment to stopping the war, to no longer running away from life. Each practice moves us back into the present with a clearer, more receptive, more honest state of consciousness.

While choosing among practices, we will often encounter others who will try to convert us to their way. There are born-again Buddhists, Christians, and Sufis. There are missionaries of every faith who insist that they have found the one true vehicle to God or to awakening or to love. It is crucial to understand that there are many ways up the mountain—that there is never just one true way.

Related: 5 Reasons I Haven’t Settled On A Buddhist School

Two disciples of a master got into an argument about the right way to practice. As they could not resolve their conflict, they went to their master, who was sitting among a group of other students. Each of the two disciples put across his point of view. The first talked about the path of effort. He said, “Master, is it not true that we must make a full effort to abandon our old habits and unconscious ways? We must make great effort to speak honestly, be mindful and present. Spiritual life does not happen by accident,” he said, “but only by giving our wholehearted effort to it.” The master replied, “You’re right.”

The second student was upset and said, “But Master, isn’t the true spiritual path one of letting go, of surrender, of allowing the Tao, the divine to show itself?” He continued, “It is not through our effort that we progress, our effort is only based on our grasping and ego. The essence of the true spiritual path is to live from the phrase, ‘Not my will but thine.’ Is that not the way?” Again the master replied,”You’re right.”

A third student listening said, “But Master, they can’t both be right.” The master smiled and said, “And you’re right too.”

There are many ways up the mountain, but each of us must choose a practice that feels true to his own heart. It is not necessary for you to evaluate the practices chosen by others. Remember, the practices themselves are only vehicles for you to develop awareness, lovingkindness, and compassion on the path toward freedom, a true freedom of spirit.

As the Buddha said, “One need not carry the raft on one’s head after crossing the stream.” We need to learn not only how to honor and use a practice for as long as it serves us—which in most cases is a very long time—but to look at it as just that, a vehicle, a raft to help us cross through the waters of doubt, confusion, desire, and fear. We can be thankful for the raft that supports our journey, and still realize that though we benefit, not everyone will take the same raft.

Many students have come to Insight Meditation retreats to learn the Buddhist awareness practice I teach after having sampled the numerous traditions that are now available in the West. They have been initiated by lamas, done Sufi dancing in the mountains, sat a Zen retreat or two, and participated in shamanic rituals, and yet they ask: Why am I still unhappy? Why am I caught in the same old struggles? Why haven’t my years of practice changed anything? Why hasn’t my spiritual practice progressed? And I ask them: What is your spiritual practice? Do you have a committed relationship of trust with your teacher and a specific form of practice? They often answer that they practice many ways, or that they have not chosen yet. Until a person chooses one discipline and commits to it, how can a deep understanding of themselves and the world be revealed to them? Spiritual work requires sustained practice and a commitment to look very deeply into ourselves and the world around us to discover what has created human suffering and what will free us from any amount of conflict. We must look at ourselves over and over again in order to learn to love, to discover what has kept our hearts closed and what it means to allow our hearts to open.

If we do a little of one kind of practice and a little of another, the work we have done in one often doesn’t continue to build as we change to the next. It is as if we were to dig many shallow wells instead of one deep one. In continually moving from one approach to another, we are never forced to face our own boredom, impatience, and fears. We are never brought face to face with ourselves. So we need to choose a way of practice that is deep and ancient and connected with our hearts, and then make a commitment to follow it as long as it takes to transform ourselves. This is the outward aspect of taking the one seat.

Once we have made the outward choice among the many paths available and have begun a systematic practice, we often find ourselves assailed from within by doubts and fears, by all the feelings that we have never dared experience. Eventually, all of the dammed-up pain of a lifetime will arise. Once we have chosen a practice, we must have the courage and the determination to stick with it and use it in the face of all our difficulties. This is the inward aspect of taking the one seat.

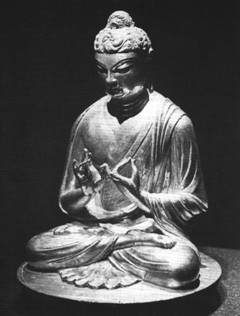

There are stories about how the Buddha practiced when he was assailed by doubts and temptations. The teaching about his commitment in the face of his challenges is called “The Lion’s Roar.” On the night of his enlightenment, the Buddha had vowed to sit on his one seat and not get up until he had awakened, until he found a freedom and a joy in the midst of all things in the world. He was then attacked by Mara, temptation in the mind. After flinging every force of temptation and difficulty at the Buddha to no avail, Mara then challenged the Buddha’s right to sit on that spot. The Buddha responded with a lion’s roar and called upon the Goddess of the Earth to bear witness to his right to sit there, based on the thousands of lifetimes of patience, earnestness, compassion, virtue, and discipline he had cultivated. At this, the armies of Mara were washed away.

We need to take the one seat, as the Buddha did, and completely face what is true about this life. Make no mistake about this, it is not easy.

Later, as the Buddha taught, he was challenged by other yogis and ascetics for having given up austerity: “You eat beautiful food that your followers put in your bowl each morning and wear a robe in which you cover yourself from the cold, while we eat a few grains of rice a day and lie without robes on beds of nails. “What kind of a teacher and yogi are you? You are soft, weak, indulgent.” The Buddha answered these challenges, too, with a lion’s roar. “I, too, have slept on nails; I’ve stood with my eyes open to the sun in the hot sands of the Ganges; I’ve eaten so little food that you couldn’t fill one fingernail with the amount I ate each day. “Whatever ascetic practices under the sun human beings have done, I, too, have done! Through them all I’ve learned that fighting against oneself through such practices is not the way.”

Instead, the Buddha discovered what he called the Middle Way, a way not based on an aversion to the world, nor on attachment, but a way based on inclusion and compassion. The Middle Way rests at the center of all things, one great seat in the center of the world. On this seat the Buddha opened his eyes to see clearly and opened his heart to embrace all. Through this he completed the process of his enlightenment. He declared, “I have seen what there is to be seen and known what there is to be known in order to free myself completely from all illusion and suffering.” This, too, was his lion’s roar.

We each need to make our lion’s roar—to persevere with unshakable courage when faced with all manner of doubts and sorrows and fears—to declare our right to awaken. We need to take the one seat, as the Buddha did, and completely face what is true about this life. Make no mistake about this, it is not easy. It can take the courage of a lion or a lioness, especially when we are asked to sit with the depth of our pain or fear.

When we take the one seat on our meditation cushion we become our own monastery. We create the compassionate space that allows for the arising of all things: sorrows, loneliness, shame, desire, regret, frustration, happiness. In a monastery, monks and nuns take robes and shave their heads as part of the process of letting go. In the monastery of our own sitting meditation, each of us experiences whatever arises and again and again as we let go saying, “Ah, this too.” The simple phrase “This too, this too” was the main meditation instruction of one great woman yogi and master with whom I studied. Through these few words we were encouraged to soften and open to see whatever we encountered, accepting the truth with a wise and understanding heart.

Whatever practice we have chosen we must use in this fashion. As we take the one seat we discover our capacity to be unafraid and awake in the midst of all life. We may fear that our heart is not capable of weathering the storms of anger or grief or terror that have been stored up for so long. We may have a fear of accepting all of life, what Zorba the Greek called “the “Whole Catastrophe.” But to take the one seat is to discover that we are unshakable. We discover that we can face life fully, with all its suffering and joy, that our heart is great enough to encompass it all.

♦

Excerpted from A Path With Heart by Jack Kornfield. Published with permission of Bantam Books, a subsidiary of Bantam Doubleday Dell.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.