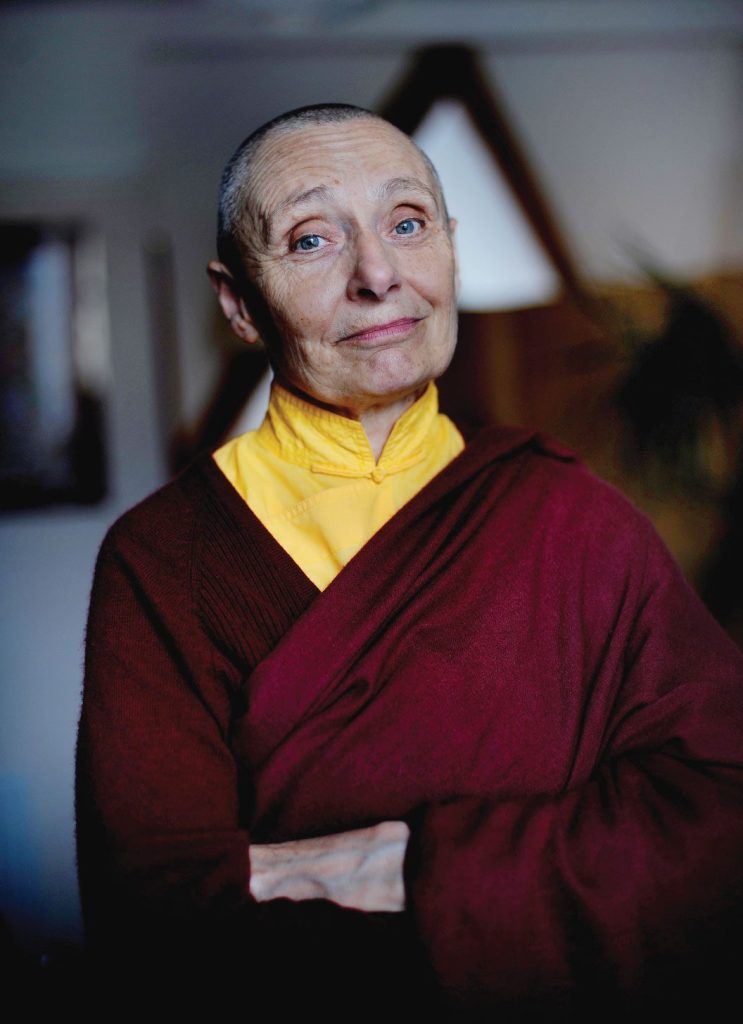

Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo was born Diane Perry during the Blitz, in 1943, the daughter of an East End charlady and a fishmonger. She decided she was a Buddhist in 1961, at the age of eighteen, traveled by sea to India in search of a teacher, and met her root guru, the eighth Khamtrul Rinpoche, on her twenty-first birthday. She became the second Western woman to be ordained as a Tibetan Buddhist nun three weeks later. At thirty-three, with her lama’s blessing, Tenzin Palmo took up residence in a six-by-six-foot cave, 13,200 feet up in the Himalayan valley of Lahaul, and lived there for twelve years. Since then, she has given her uniquely practical teachings around the world in an effort to raise awareness and funds for the Dongyu Gatsal Ling Nunnery, in Himachel Pradesh, India, which she founded in 2000.

Lucy Powell interviewed the sixty-six-year-old nun while she was in London this year, giving her final teaching tour before retiring to India.

Your example is at once inspirational—that a Westerner, and a woman, could meditate in solitary retreat for such a prolonged period—and dispiriting: unless we can sit in a Himalayan cave for over a decade, we won’t make any real progress on the path. Certainly we have to do the work. This is true. It is really very impressive how many excuses we can invent for why we aren’t sitting. This idea we have that when things are perfect, then we’ll start practicing—things will never be perfect. This is samsara!

I remember once I was in the cave getting all depressed because the snows would melt in the spring and water would run down the back wall, making everything wet. Finally, I thought, “But didn’t the Buddha tell us it was this way? What is the first noble truth, after all? What do we expect? Why make such a big fuss when we suffer?” After that, I didn’t have any trouble.

Call something an obstacle, it is an obstacle. Call it an opportunity, it is an opportunity. Nothing is extraneous to the spiritual life. This is very important to understand.

So why retreat? Retreat is, in a way, a quick fix. I often think of the nuns of Mother Teresa’s order: they’re not picking up the dead and dying all day long—half the day is spent in prayer. If one is everlastingly giving out without breathing in, one becomes stressed and burned out.

Twelve years is an extremely long fix. Each of us has something to do in this lifetime; we have to find out what it is and do it. Retreat is what I was born to do. I was extremely happy in the cave and very grateful to be there. It was a rare opportunity.

Did you experience periods of doubt or fear? I find talking about my time in the cave extremely boring; it was a lifetime ago. But, no, nothing made me worried or afraid. Hundreds of thousands of hermits through the ages have done exactly the same thing, and ninety-nine percent of them were fine. You’re very busy doing your practices—you’re not twiddling your thumbs all day—and you get into a state of mind where you accept that whatever is happening is happening. Even the most awful things that happen, if you’re centered, you’ll be okay. If not, the most trivial thing will send you off. It has nothing to do with the experience or the circumstance: it is the attitude that’s important. We have to stop clinging to the conditioned path and learn to be open to the unconditioned path.

How do we develop that attitude of openness? This is the question. Our fundamental problems are our ignorance and ego-grasping. We grasp at our identity as being our personality, memories, opinions, judgments, hopes, fears, chattering away—all revolving around this me me me me. And we believe that that self is actually a solid, unchanging entity that sets us apart from all the other entities out there. This creates the idea of an unchanging permanent self at the center of our being, which we have to satisfy and protect. This is an illusion. “Who am I?” is thus the central question of Buddhism. Do you see?

Most of the time, what we do is work to try to protect this false me, mine, I. We think the ego is our best friend. It isn’t. It doesn’t care if we are happy or unhappy. In fact, ego is very happy to be unhappy. And we must be conscious of not using the spiritual path as another conduit for the ego—a bigger, better, more spiritual me.

There are practices we can use against this egocherishing. In the company of very sick people who are suffering, one can visualize that one is taking in their fear and pain, in the form of dark light or smoke, pulling out sickness and negative karmas, and directing them toward the little black pearl of our self-concern. And it will start to disappear, because, really, the very last thing the ego wants is other people’s problems.

If we do experience pain or suffering ourselves, we can use it. We’re conditioned to resist pain. We think of it as a solid block we have to push away, but it’s not. It’s like a melody, and behind the cacophony there is tremendous spaciousness.

What do we do when thoughts arise in meditation? The thoughts are not the problem. Thoughts are the nature of the mind. The problem is that we identify with them.

How do we learn to dis-identify with them? Practice.

What of emotions like anger? The Buddha said that it’s greed, not anger, that keeps us on the wheel. Nobody’s chaining us down: we’re clinging on with both hands. Many people come to me saying that they want to eradicate anger; it’s not difficult to see that anger makes us suffer. But very rarely do people ask me how to be rid of desire.

We have to cultivate contentment with what we have. We really don’t need much. When you know this, the mind settles down. Cultivate generosity. Delight in giving. Learn to live lightly. In this way, we can begin to transform what is negative into what is positive. This is how we start to grow up.

Can you explain a bit about the difference between love and attachment? Attachment is the very opposite of love. Love says, “I want you to be happy.” Attachment says, “I want you to make me happy.”

Do you detect a rising spiritual consciousness in the West? What I see is that modern society is based on what Buddha called the three poisons—greed and aversion arising from [delusion, which is] a very strong sense of self. That’s what our society encourages, believing that the more greedy and self-assertive we are, the happier we will be. So the very path to suffering is now being touted as the path to happiness. Naturally, people are very confused.

Nonetheless, I feel that people in the West have an advantage. Having so much material prosperity, they have already experienced everything our society tells us will give happiness. If they have any sense at all, they can see that it does not bring happiness. At most, it gives pleasure, which is very short-term; genuine happiness must lie elsewhere. If you’ve never had those things, you can still imagine that they would give the kind of satisfaction their promoters assure us they do. But as the Buddha said, desire is like salty water—the more you drink, the thirstier you become.

So why are we still drinking? The crux of the matter is laziness. Even when we know what we should be doing, we choose what seems to be the easier path. We’re gods acting like monkeys. We’re standing in our own light: we don’t see who we really are.

But how do we step out of our own light, step onto the unconditioned path, and realize our limitless potential? Our mind is a treasure. But it’s very absorbent, so we must also be very discriminating in what we hear, read, and see. And in the spiritual life, our fence is our ethics. If we know we are living ethically to the best of our ability, the mind will become peaceful. We will attract the same kinds of people we really are. If we have a mind full of defilements, we will attract that to us. Therefore we have to purify our mental state, because whatever is within we will project out. You bring people toward you by your work and by karma. You have to be ready, when someone of a higher level is in front of you, to meet them. You do this by connecting to your source.

But if the Buddha were here, all he could encourage you to do would be to practice. Nobody else can do our work for us—it’s up to us to do it or not. Swimming upstream toward the source takes effort and determination. Sorry, there is no quick fix. But in the end it is the only thing that’s worthwhile. The key is practice. But don’t put it on the shrine: take the key, open the door, and walk out of the prison. There are no obstacles.

♦

Dharma Talk: The Eight Worldly Concerns with Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.