Larry Rosenberg is the founder of the Cambridge Insight Meditation Center (CIMC) and a guiding teacher of Insight Meditation Society (IMS) in Barre, Massachusetts. His new book, Breath by Breath, was recently published by Shambhala. Born to Russian-Jewish immigrants in 1932, Rosenberg grew up in Brooklyn; his father, who had Marxist leanings, came from fourteen generations of rabbis, but thought “that only an idiot goes into religion.”

Rosenberg went to Brooklyn College, and received his Ph.D. in social psychology from the University of Chicago. A highly coveted job in the Department of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School followed. But this turned out to be a “staggering” disappointment and he returned to the University of Chicago, where he began to experiment with hallucinogens. During a trip to Mexico in the 1960s, he met a cowboy-turned-holy-man who told him, “Don’t waste your time with drugs; you should start meditating.”

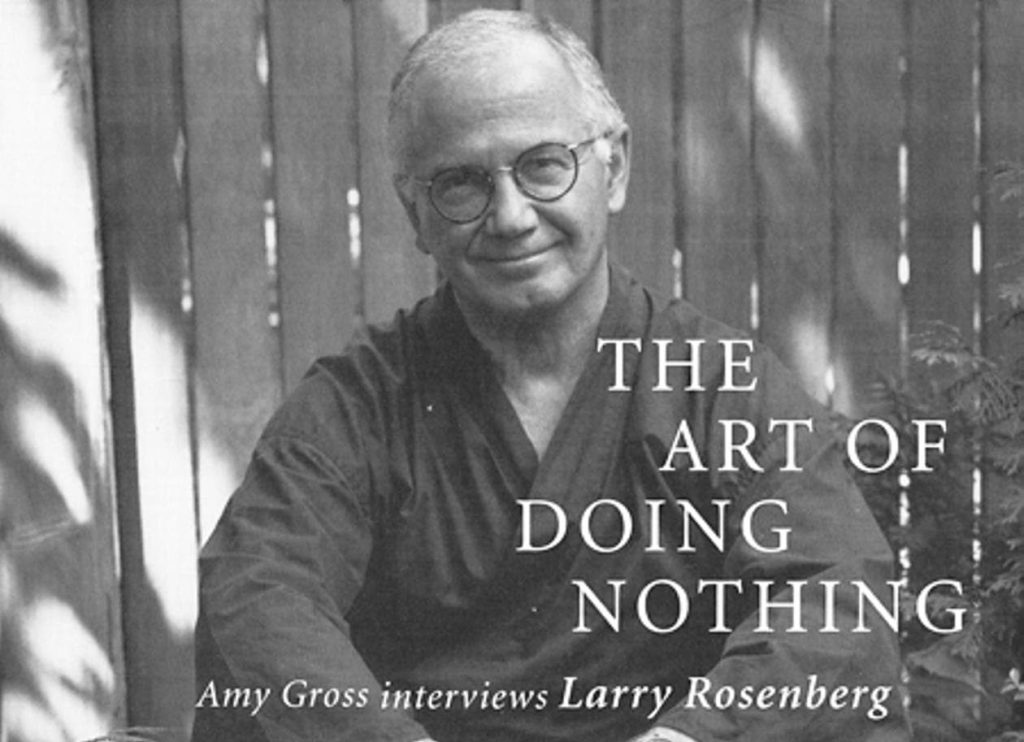

Thirty-five years later, Rosenberg is sitting in a wing chair in CIMC, talking to Tricycle’s contributing editor Amy Gross about the evolution of his own practice.

***

Tricycle: Who was your first teacher?

Rosenberg: Krishnamurti. I met him in 1968 while I was teaching at Brandeis University. Brandeis had this program where they’d invite a person to give talks for a week. I didn’t know who Krishnamurti was, but fortunately for me, no one else did either so we started taking walks and talking. I’d never met anyone so awake. I’d never been listened to so totally and I found it quite unnerving at first. Then, as I got to know him, I just felt so at home with him. I told him that I was a professor, but the whole academic thing was dying out from under me. I’d been extremely ambitious—on fire to get a Ph.D. and a good job—but now I thought the old cliché “publish or perish” should really be “publish and perish.”

Before Krishnamurti I’d never verbalized how I felt because I didn’t have the confidence. What he did that was invaluable was, he confirmed my perception. He said, “Just go on teaching and start paying attention to yourself. Start noticing how you actually live.” That’s a phrase he’d say over and over—“how you actually live.”

Tricycle: Where did you go from there?

Rosenberg: I started doing everything. Krishnamurti. Vedanta. I was on my way to India for a Sanskrit-Vedanta training program when a friend of mine introduced me to Seung Sahn, a Zen Master from Korea. I went on a retreat, and after that, there was no reason to go to India. I thought, “Boy, I’ve accomplished more in four days of meditation than in all the years of talking about texts.”

Tricycle: How did you know what you were trying to accomplish?

Rosenberg: I’d had a taste on drugs of a pristine clarity and a feeling of tremendous joy and peace and love. And once or twice I had it doing a primitive kind of meditation, the best I could do based on books and what Krishnamurti had said.

And that was the beginning of the end of my academic career. What I’d learned at Harvard was that I was looking for happiness in the wrong place, because if I couldn’t be happy at Harvard, where could I? And finally, the last two years or so at Brandeis I knew that I had to drop out of the university and go into this full-time.

Tricycle: How did you live after you dropped out?

Rosenberg: For about a year-and-a-half I just crashed in different places, including Asia. Somehow I always had a place. For a while I lived at Seung Sahn’s center near Providence, Rhode Island, wore the robes, and studied with him. He was grooming me to teach and I traveled with him as his aide.

Tricycle: What was your practice then?

Rosenberg: Mostly koans. And after three or four years he suggested that I spend a year at his monastery in Korea, which I did.

Tricycle: What led you from Korean Zen to vipassana?

Rosenberg: After Korea, I went back to the Zen Center, where there was a huge amount of ritual—chanting twice a day, bowing, robes, a stylized way of eating, so many ceremonies it seemed we were celebrating something every other week.

Then my close friend Jon Kabat-Zinn—we’ve gone through all these things together for thirty-five years—went on a vipassana retreat, and he pretty much grabbed me and said, “Larry, I found what you’ve been looking for.” Because I’d always say, “If we could only get rid of all this ceremony, all this stuff.” But I said, “Look, Jon, Zen is fine for me; I just want to stay here.” He said, “If I have to tie you up and throw you into my pickup truck, I’m going to take you on the next retreat.” So for my birthday he gave me a present of a retreat—it was led by Jack Kornfield.

Tricycle: And was it just what you were looking for?

Rosenberg: It was love at first sight. The retreat was basically sit-and-walk until you’re blue in the face. Breathing was the main method, and making mental notes. There was no chanting. There was no special way to eat except mindfully. Oh my God, what a relief! I didn’t realize how much I didn’t want to carry around all that Asian form and custom and just be an American guy who wanted to do this stuff.

The heart of the whole thing is understanding. Not intellectual understanding, although that’s a way to begin. It’s deeply seeing into yourself. And that to me is different from concentration, which can of course facilitate such clear seeing. Many things help you with concentration, like chanting or bowing, so they can be useful parts of practice. But finally, there is no substitute for insightful seeing or for understanding how you create suffering for yourself; and in the process—in seeing into and through it—how to let go of it. It’s a life of awareness. That’s my passion. Now, there’s a school of Zen that emphasizes just-awareness of what is, and I could easily have gone in that direction. That’s Soto Zen, and a practice called shikan-taza—just sitting—and when that ripens, that to me is mature practice. It’s nothing. You sit and you’re just totally attentive to what’s there. What I teach, anapanasati, leads to that, to more and more simplicity until finally we don’t need techniques and methods, even the breath. [Anapanasati is where breathing is used as an exclusive object of attention to develop concentrated focus; then awareness grounded in the breathing is used to see clearly into the impermanent and empty nature of all formations. Letting go into freedom emerges into insight. —LR] I don’t impose it on people. I let them come to it naturally. But for me, I’ve always been much more drawn to just awareness of the way things are. Krishnamurti—whose teaching is a brilliant modern commentary on the fundamental teaching of mindfulness—started me that way, and I’ve always come back to it.

Tricycle: It’s a hard way to start, don’t you think?

Rosenberg: I won’t say it’s impossible, but yes, I agree, it’s a hard way to start.

Tricycle: Why did you open the Cambridge Insight Meditation Center?

Rosenberg: I’d: been teaching at a bookstore two nights a week. And a lot of people started coming, and then they started saying we needed a center. I wasn’t thrilled with that. I had avoided certain kinds of responsibilities my whole life. But after a few years it became obvious that it would really be great if there was some place—IMS plus this urban place—because people were coming back from their long retreats at IMS and there was no place to practice. Also, I was evolving a way of teaching that took daily life very seriously.

Tricycle: You mean in contrast to retreat time?

Rosenberg: Yes, the idea was that people could go off and do retreats and we’d keep the sitting practice alive and also encourage them to go back to their families, school, job, and then tell us about it. And we would respond not like therapists but from a dharma point of view. Could the practice be helpful to the work and the marriage and school, etc.? It’s quite a challenge, one I welcome: What do these teachings have to offer in terms of how people can live in the world?

Tricycle: How did that differ from your own studies?

Rosenberg: Most of our teachers had been celibate monks from Asia. They had very little direct experience with women, some of them had never had a job or touched money, etc.—and they were giving us advice. To me, some of their advice seemed limited. Their advice to men about women—I’m making a bit of a joke about it, but it was sort of like: “Take care of the wife and kids so they’re adequately fed and housed and get some schooling, so they’re not a problem.” Basically it’s so that you can get on with the real thing, which is to sit. It isn’t seeing marriage itself or children or work as dynamic situations that have a lot of energy in them, that are quite challenging, and that if looked at in a certain way are not inferior to sitting as a way of growing spiritually.

Tricycle: That view westernizes the dharma, doesn’t it?

Rosenberg: Yes, I think Westerners lack respect for their own spiritual maturity. It’s as though Asia owns spirituality, and we’re these barbarians, beseeching, “Oh, Bhante, please come over and tell us how to live.” But I’ve been to Asia, and they’re just as screwed up as we are. And there’s some real wisdom in our culture; the West has a tradition, too, of compassion and wisdom. And some people who aren’t even religious have it. When I was in Asia I totally did whatever an Asian layperson would do—I have the deepest respect for this tradition—but Asia does not have a monopoly on kindness. In Asia, being a layperson is—from the point of view of meditational practice—considered second-class. I personally think that the monastic life does optimize your possibilities for breaking through to awakening. But it’s by no means a guarantee. Most monasteries are hardly crammed full of enlightened people.

But we need a teaching that addresses the lives we actually live. We do need to handle money. We are in relationships. We do need to eat more than once a day. The problem isn’t eating or sex or money; it’s that we don’t know how to use these energies. The monastic strategy is: Don’t touch it; it’s dangerous. So the monks don’t handle money, etc. To me that’s not in and of itself particularly holy. It’s a strategy, a monastic strategy to get free. I’m all for it—if you’re going to be a monastic.

Tricycle: And for lay practitioners?

Rosenberg: Our challenge is to learn how to use money and food and relationship correctly and not to look at these realms as tainted. And I didn’t see fully adequate help coming from Asians. What I’ve learned, I’ve learned from the Buddha’s teaching of the Four Noble Truths and my own pain, from not knowing how to do these things.

Tricycle: Could you describe how your own practice has changed over the years?

Rosenberg: Throughout all sorts of different schools and practices, two things have survived. One is an abiding interest in the breath. And the other is just ordinary mind power, just awareness itself. That’s what I got from Krishnamurti, and it’s in all the Buddha’s teachings. It’s just to be attentive to the way things are. In Pali, the word for mindfulness is sati and one of the definitions of it is “that which sets things right.” I don’t know if you’ve seen this in the practice, but when mindfulness touches things, they’re less problematic or not a problem at all. It’s magical. What I learned from anapanasati was that the breath is not simply to calm yourself or steady yourself or develop concentration; it can nourish awareness throughout. You use the breath the way everyone else does—to calm down—but it stays with you as you investigate the body, feelings, and all the different mind states, and begin to see that they’re impermanent and lack an enduring core; they’re not self.

Tricycle: So the breath is like background music or—

Rosenberg: It helps keep you on target. It can sustain and strengthen the awareness. It can cut down unnecessary thinking and even eliminate thinking, for periods of time anyway. It’s particularly helpful with difficult emotions that are hard to observe. It’s like a soothing friend holding your hand as you walk into fear or loneliness or anger, encouraging you to stay with it. And if you feel like running away, observe that. And the breath is always there, in, out, in, out. In the communities I’m used to teaching in—highly educated, intellectual people who live complex lives, whose work involves coordinating many activities, the use of computers, social relations—their minds have become very, very complicated. Too complicated. For those people, the breath is a relief. It’s like, “Phew!”

Tricycle: What happens to you now when you sit?

Rosenberg: The breath is still there. But my practice now for the most part is doing nothing. I just sit there. I know it sounds dopey [laughs]. Typically I’ll start off with the breathing, but sometimes not. I get calm and clear pretty quickly. Sometimes I’ll just spend a whole sitting really deeply in samadhi, which is very useful, especially if I’m tired—tremendous energy comes from it. So I’m not investigating it; it’s not vipassana at all. I give exclusive attention to the in-and-out breathing. And it strengthens the mind. It’s like a sanctuary that you can drop into to get away from everything for a while. Even five minutes of conscious breathing, and I’m ready to do what has to be done in terms of people and work. So typically, I start off with the breath. And sometimes that’s all I’ll do. But ninety-nine percent of the time, I just open the field of attention. If I had to put it into words, it’s learning the art of doing absolutely nothing. So you’re sitting there, attentive, and enjoying the show.

Tricycle: What’s “the show”?

Rosenberg: Whatever comes up. A thought. A sound. A sensation. You don’t reach out for anything. You just let life bring stuff to you. Or there’s silence. Many people have some ambivalence about silence—they fear it, or don’t value it. Because we only know ourselves through thinking and speaking and acting. But once the mind gets silent, the range of what’s possible is immeasurable. So first you taste the silence. Then you realize that it’s not a vacuum or dead space. It’s not an absence of the real stuff; it’s not that the real stuff is the doing, the talking, and all that. You get comfortable in it and you learn that it’s highly charged with life. It’s a very refined and subtle kind of energy. And when you come out of it, somehow you’re kinder, more intelligent. It’s not something that you manufacture—it’s an integral part of being alive. And it’s vast. We’ve enclosed ourselves in a relatively small space by thinking. It binds us in, and we’re not aware that we’re living in a tiny, cluttered room. With practice, it’s as if the walls of this room were torn down, and you realize there’s a sky out there.

Tricycle: Have your reasons for practicing changed over the years?

Rosenberg: I’d say that what got me into this doesn’t bear a lot of resemblance to why I do it now. The original motives were immature and romantic, having to do, at first, with wanting to get a natural organic high without the side effects of drugs. But after a while, getting high from meditation is beside the point. The point is getting free. That’s not only of benefit to you—I say this to people who think the practice is very self-centered: The greatest gift you can give to others is to become less of a problem through understanding yourself. We don’t know how to live together as human beings. To me, practice is not an act of ideology; it’s an act of intelligence or wisdom.

“Terms like ‘enlightenment’ or ‘awakening’ are important because sometimes people forget what this practice is really about. It’s not about making yourself happier. It’s not liberation of the self; it’s liberation from the self.”

Tricycle: Is getting free the same as getting enlightened?

Rosenberg: If you say, “Am I practicing in order to get enlightened?” the answer is yes. But that sounds stupid to me. The process of liberation is right now. Anyone who has practiced for a while knows there are dramatic openings—that “Wow!” where you see things very clearly. It helps a lot when you have that. But throughout any ordinary day there are so many points where, if you pay attention, you can see how you’re suffering unnecessarily. Awareness sees it and in the seeing of it, there’s letting go and you’ve liberated yourself. So liberation isn’t just a goal. It’s actually a practice. You are liberating yourself in this moment—and that’s all we’ll ever have, these moments. If you have even a little glimpse of clear mind, or that in us which is untouched by any kind of cultural conditioning, it’s hard to settle for anything less. And terms like “enlightenment” or “awakening”—which I prefer—are important because sometimes people forget what this practice is really about. It’s finally about enlightenment, about awakening, about liberation. It’s not about making yourself happier. It’s not liberation of the self; it’s liberation from the self.

Tricycle: As we evolve an American Buddhism, do we need an alternative to the phrase “not-self”? We’re raised to develop an independent, strong self. I don’t know if Asians have an easier time with the idea of the end of ego.

Rosenberg: Ego is a universal thing. Egomania is wherever you look. It’s hard for everybody to understand this “not-self” stuff. I say, Are you willing to look at your mind and learn? See what happens when you’re an egomaniac. If you find that it’s not a skillful way to live, that you’re getting hurt over and over, this is why. But you have to see that yourself. It’s not a new ideology to adopt: “I believe in not-self.” So what? Beliefs are so easy to come by. That isn’t what the Buddha is saying. The Buddha is saying, “Investigate what you call your own personal identity, and find out what that really is.”

Tricycle: Are you different from when you started?

Rosenberg: I think there’s been improvement in behavioral qualities, personality. But what practice is about is something that is beyond measure, and if you practice, you will taste that. And it doesn’t mean that you will have a perfect personality if you taste awakening. People think that’s true. But you have to express yourself through the vehicle that you have. Maybe my packaging has improved, and I don’t think that’s trivial—I’m probably easier on the people in my life. But in another sense, I don’t want to overestimate it. There’s a story that I like very much. The Zen master Sawaki Roshi was walking with a disciple who described himself as a shy, awkward person. Sawaki Roshi was a very confident, charismatic person. So they were walking and the disciple said, “If I keep practicing with you for the next thirty years, will a weak person like me become stronger?” And Sawaki Roshi said, “No. Meditation is useless. I was just born this way.” He was trying to make it not a means-end kind of thing. When people would ask Sawaki Roshi about the value of meditation, he sometimes said, “Oh, this sitting? It’s absolutely useless. But if you don’t do this useless thing wholeheartedly, your life will be useless.” Figure that one out. In a certain way you just practice. Don’t worry about “Am I getting better?” and the rest of it. Just practice dharma for its own sake and let things take care of themselves.

Tricycle: You’re suggesting that the changes wrought by practice are very subtle, but in your case, practice redirected your life.

Rosenberg: I think one of the things practice does is bring you to your own unique way of flowering. Some people are afraid, “If I meditate, will I have to quit my university life or end my marriage?” I don’t know. I think it shows you what’s true for you, and then it’s up to you to live that or betray it. You don’t have to leave the world. It’s not about being in or out of the world. You can be a monk and be ruled by ego.

Tricycle: Can you be a CEO and not ruled by ego?

Rosenberg: Why not? I think Buddha was a great CEO. Jesus was an amazing CEO. They were incredible in the way they mobilized people and orchestrated things, got a lot done in just one short life. I’m not saying that it’s easy, but in principle, why not? The suffering isn’t in functioning as a CEO; it’s that you think you are a CEO. Dharma ultimately is about finding out that you’re absolutely no one. What a relief. When you’re no one, finally you’re real. I mean, you’re living from full presence rather than from all these representations of the self that you identify with: I’m a CEO! I’m a great editor! You’re more alive than you’ve ever been. And when you practice, you don’t have to wait a long time. We all have our moments of clarity, even now.

How Breathing Really Is

It is important to emphasize, in discussing the art of meditation (and the practice as you continue it becomes an art, with many subtle nuances), that you shouldn’t start out with some idea of gaining. This is the deepest paradox in all of meditation: we want to get somewhere—we wouldn’t have taken up the practice if we didn’t—but the way to get there is just to be fully here. The way to get from point A to point B is really to be at A. When we follow the breathing in the hope of becoming something better, we are compromising our connection to the present, which is all we ever have. If your breathing is shallow, your mind and body restless, let them be that way, for as long as they need to. Just watch them. If you find yourself disappointed with your meditation, there’s a good chance that some idea of gaining is present. See that, and let it go.

One place where ideas of gaining typically come in, where people get obsessive about the practice, is in the task of staying with the breathing. We take a simple instruction and create a drama of success and failure around it: we’re succeeding when we’re with the breath, failing when we’re not. Actually, the whole process is meditation: being with the breathing, drifting away, seeing that we’ve drifted away, gently coming back. It is extremely important to come back without blame, without judgment, without a feeling of failure. If you have to come back a thousand times in a five minute period of sitting, just do it. It’s not a problem unless you make it into one.

Each instance of seeing that you’ve been away is, after all, a moment of mindfulness, as well as a seed that increases the likelihood of such moments in the future. If you already had some kind of laser-like attention that never wavered, you wouldn’t need to practice meditation at all. The object of these two contemplations isn’t to make your breathing perfect. It’s to see how your breathing really is.

♦

Excerpted with permission from Breath by Breath: The Liberating Practice of Insight Meditation (Shambhala)

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.