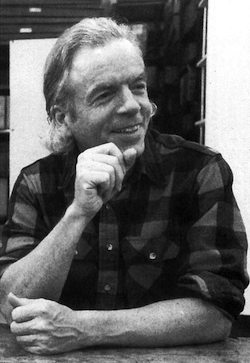

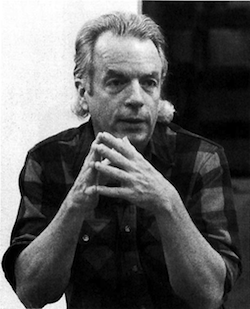

Spalding Gray, a writer, actor, and performer, has created a series of fourteen monologues which have been performed throughout the United States, Europe and Australia, including Sex and Death to the Age 14; Booze, Cars and College Girls; A Personal History of the American Theater; India and After (America); Monster in a Box; Gray’s Anatomy; and the OBIE Award-winning Swimming to Cambodia.

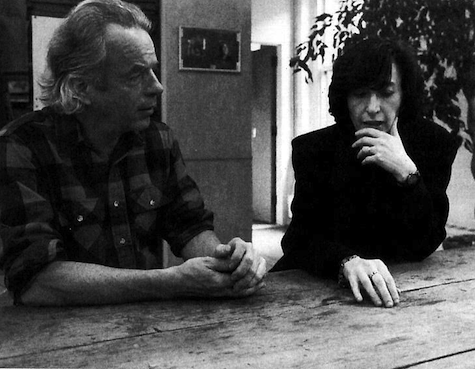

Francine Prose is the author of eleven books of fiction. Her latest book, Guided Tours of Hell, will be available in January from Holt/Metropolitan. She interviewed Gray in the Spring of 1996 in New York City.

Prose: Do you think of yourself as a Buddhist?

Gray: No. Some people think that I am, I don’t know why. They say “us Buddhists,” or “you Buddhists.” I only got interested in Buddhism when I read that it was supposed to be a philosophy. And I thought, “Well, I’m interested in philosophy.” I got to the point where I could read or discuss the philosophy of Buddhism. But I couldn’t get around the religious construction. As soon as it got to be dogmatic in any way, as soon as the philosophy was no longer open, I’d get claustrophobic.

Prose: What was the original attraction?

Gray: The original attraction was the concept of no self: the self as an illusion. For me that’s a dangerous business, as it was for all of the beatniks that grabbed on to it. Now, one of the best lines I ever heard, speaking of the beatniks, is when Gregory Corso was teaching out at the Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado. Everyone was working on trying to lose the ego, which was the big thing to do in the early seventies and the sixties, and I was figuring out how to lose mine. I heard that Gregory Corso ran into one of the classrooms, you know, no teeth, and just yelled, “How many of you here think you have an ego to lose, raise your hands.”

So, the not-self was an original attraction for me, and now I am trying to figure out when I first experienced it, or if I ever experienced a self. Or maybe I’m really looking at Buddhism because I’m experiencing a pathology in me, and I’m equating the pathology with a philosophy, and that they don’t really interconnect.

Prose: Once you start talking about the self, it gets very terrifying. But when you talk about self-consciousness—good or bad—I can understand the desire to lose that.

Gray: Yeah. See, I don’t see self-consciousness as a pejorative. I think of self-consciousness as consciousness of self. I see it as awareness.

Prose: It’s good and bad. There are people so paralyzed by self-consciousness that they can’t do anything. But, on the other hand, if you’re not conscious of yourself, how can you become conscious of the world? Where do you start paying attention?

Gray: Where are the boundaries? Certainly something that led me to the philosophy was the Buddhist idea of interconnection. Because ultimately, I do have a sense that that’s an essential truth. For me there’s also a paradox because I have a struggle in my own life with boundaries.

Prose: The last thing you need is no boundaries!

Gray: Yeah. So a lot of what attracted me in the Buddhist philosophy was egocentric, in the sense of “Oh my God, here’s a philosophy that kind of sounds like what I am.” But it’s integrated. I got a head start on it, but I’ve individualized it and not integrated it.

In other words, I’m having boundary problems with my accountant now. We kind of overflow. I know that we’re all the same, but at the same time, he’s got my money. You know, I don’t want to share my money with him.

Prose: It’s good to have boundaries with your accountant.

Gray: Yeah. The other day I had what I would call a Buddhist experience, or something that would tie into the Buddhist philosophy, but it was also my own experience. I was having a pita stuffer up on West Broadway, outdoors, because no one was outside and it was real claustrophobic in, and I was sitting there thinking, “I don’t even know if I can eat this thing because I am really feeling fragmented today.”

Prose: Too fragmented to eat?

Gray: I couldn’t find my mouth; I felt very Picassoian inside. And I started going, “But, wait a minute. I am feeling fragmented. Who’s this I that’s seeing the fragmentation?” And then I went, “Uh-oh, here’s another I. It’s seeing I that’s seeing the fragmentation. Oh, my God, here’s this one that’s seeing that.” And it really got dizzying. I just went into a little trance. Actually, what brought me out of it was a woman passing by. I just focused completely on her. That brought me completely back into the world.

Prose: At that point what you didn’t really want was the sandwich.

Gray: No, I didn’t want the sandwich or the woman. I wanted to get lost in the hall of mirrors. But I kept thinking, “Is this a Buddhist thing?” And, “How will I ever make a living?” And, “Is this what it’s all about? Is this insanity or what?”

I think that there are parts of us that are thinking like Buddhists all the time. So when Buddhism descended on America, or was brought into America, we suddenly thought, “Oh, but I think like that. Does that make me a Buddhist?” No, it makes me a human being.

Prose: What confuses me about Buddhism is that all those things seem Buddhist. I mean, the consciousness of the self eating the sandwich, and the self watching the self eating, the self . . . and then the getting completely beyond that and just eating the sandwich.

Gray: Right. That’s what finally happened, actually. In my new monologue I say I’m out skiing and I got hungry. “The Zen Miracle,” I call it, because it’s not just looking at my watch and saying, “It’s lunchtime.” It’s a feeling of real hunger and being in contact with that and then simply eating the food. And probably that is the full circle that, when it’s working, happens. You go the whole trip. You go, “No self. No self. Eat.” I don’t know if that’s what happens at death. One of the things, certainly, that’s annoyed me recently about what I would call very dogmatic or formulaic Tibetan Buddhism has been this book—and it’s a very popular book—The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying. I haven’t read the whole book, but its fear factor and its hellfire and brimstone factor go something like this: If you—I’m paraphrasing—if you think you’re confused now—which I do—just wait till you die. You know, it’s like finger-shaking. You will go into total disorientation and such confusion for forty-nine days. If you’re not on top of it, you’ll probably slip into a dirty old womb somewhere and you’ll have a really low birth.

I used to sit in Robert Thurman’s Buddhist studies classes at Columbia University, and he’d say, “Imagine the following: a small wooden ring is floating on top of the Pacific Ocean. On the bottom, a blind turtle is crawling for eternity. And every one hundred years this blind turtle comes up. The chances of its head going through that wooden ring are your chances of being reborn as a human being again.”

Prose: And what are the options if you don’t get to be a human?

Gray: You’re stuck as a scorpion. But then you get into all these discussions of class. Well, is an unconscious scorpion suffering? I mean, I look at a seagull and say, “Do I want to be that?” Well, I don’t want to be that unless it implies having the disease of consciousness. That is, being aware. I fluctuate between thinking consciousness is a disease and thinking that it’s the most beautiful thing in the world.

And of course I think that one of the wonderful things about Buddhism that attracts me is the great paradox. It’s that quality of being able to stand away and still be compassionate. That is a paradox that is operating in real Buddhists—the lamas and the people that are steeped in that school. Or I project that on them. There’s a warmth and compassion, and there’s also a disengagement. They’re in the world and not of it, and I think that’s always been attractive to me, and I don’t know why. Because I think compassion is so lacking, and that self-centeredness is so enormous. But, then again, maybe that’s the human condition.

Prose: What’s most attractive to me is that compassion, and that consciousness and mindfulness that make it possible to put compassion into practice. That’s very different from sitting in your loft and saying, “Oh, compassion is so important,” and then going out and having someone cut in front of you in line at the post office and just wanting to blow him away with a machine gun.

Gray: Yeah, most of the so-called American Buddhists haven’t got it down yet. But I think that the living Buddhists in our midst, the ones who have come here because the Chinese have kicked them out of their place, are still probably living examples of that. But then again, I’m secretly looking to see all Buddhists corrupted. Because the first thing I tell myself is that they’re not exposed to the same daily shit. They’re in a more protected environment and that enables you to be more that way. Even I’m compassionate when I stay in my loft until one o’clock in the afternoon and then I go out. If I was rushing out to work at eight o’clock in this city, it would be a lot harder. Although Trungpa Rinpoche used to say, “New York City’s the ultimate challenge. If you can sustain any kind of enlightenment here you’re in.” But the living, working world is really probably too much for most Buddhists, and it requires this kind of special location: a little island.

Prose: When you interviewed the Dalai Lama for the first issue of Tricycle, he managed to sustain it in a motel in Santa Barbara.

Gray: Right, and I said, “What do you do when you come into a motel like this?” He said, “I look around and try to see what’s interesting and then I meditate.” Well, that is a perfect setup. What do you find interesting in this motel? And that’s the big question that I missed. I’m depressed about that to this day. I faltered. I wasn’t my usual self because what I would do is usually ask that question and hold the meditation as the next question. But, I was so interested in what his meditation was that I jumped on to that. And his answer about the meditation was actually so complex that that’s one of the first times the translator kicked in. It was a very long answer and it was mainly translated. And then I realized that he isn’t doing Vipassana meditation, in which you watch your mind. He is doing a whole series of visualizations and praying for the whole world. On a lower chakra level, that’s an obsessive-compulsive nightmare. On a high chakra, it’s visualizing the world.

Prose: Do you have Buddhist friends?

Gray: They call themselves Buddhists. Do your Buddhist friends seem different from other people?

Prose: Sometimes. There’s something that comes from years of sitting there and believing in it. I certainly see those monks and think they’re different. But you’re right. Their smile looks so sweet, but how can we even read that smile?

Gray: They get into a place that has to be a very special, protected place, and not in the world, because the world is so removed from the original Buddhist concepts.

But here’s one of my bottom lines: In the face of death any coping system, any compensating system, any system of mental health that exists, must operate, in my opinion, with enormous denial. Because I have only a few more years to live, I’m enraged. I don’t want to die. I know I can’t live forever. I know all that rational stuff. But I’m operating on a two-year-old level. And that is the terror of death. I’m afraid of death. I don’t want to die forever. But all I know is that the rage and the fear is operating in me. And I don’t think it’s ugly and I don’t think it’s dishonest and I don’t think I can do away with it.

Prose: Or be told that it doesn’t matter, or that it’s just attachment to this life or this body. What I’m jealous of is not so much people who think it doesn’t matter, as people who think that there’s an order behind it, which is not exactly Buddhism, right? Maybe it’s a Catholic that I’ve always wanted to become.

Gray: I don’t know much about Catholicism because it was the other side of the tracks. I grew up as a Christian Scientist with no imagery at all, and we were just simply told that there was no such thing as matter, that we weren’t here, which you can translate as a kind of Buddhism.

Prose: They do share the idea that earthly reality is unreal compared to a higher reality.

Gray: Well, it“has”no reality compared to the other reality of death, or whatever you want to call death: eternity, infinite, infinite time, no time, space. But whatever is out there is so much larger than what’s here that it keeps undermining what’s here. So I understand the illusion part, and that’s part of why I—this may be a huge giant excuse—am so relentlessly autobiographic. Because I’m still trying to pierce the illusion. To fictionalize it would be a double illusion. I’d be too far away. I’d be floating around in space.

Prose: Which illusion?

Gray: The illusion that there’s permanence. It’s like grasping the earth all the time, saying my narrative. Saying, “I’m here. I’m here. I’m here.” Grasp. Grasp. Grasp. Grasp. And then people that are more involved in the spiritual life will say, “Oh, Spalding’s a grasper,” you know, “He’s a clinger.”

Prose: But Spalding, you’re telling stories. And that’s the thing I like best about Buddhism, or Western religion, are bible stories and teaching stories and stories about this monk and that monk. They’re not abstract; I can understand them. They’re human interest stories, and human experience, finally, is the most interesting thing.

Gray: I think so, but there are a lot of people who are trying to separate human experience from religious experience. And that’s where the agenda and dogma come in that drive me nuts. There was a reaction I had after I interviewed the Dalai Lama that actually drove me back to rethinking and remembering the existential writers, and particularly Camus. I began to think that—although I think that the Dalai Lama is a great man and a wonderful balance between the spiritual and political—my real heroes still are people that can live with the mystery and with doubt, with lack of closure, and still have some sense of humanity or morality in the face of what at best we can call the mystery, at worst, chaos, or the chaotic mystery—but just not knowing.

People ask me why I don’t laugh a lot, and I say it’s because I don’t find things funny. I find them absurd, and it makes a different kind of feeling in my stomach. In essays, Camus says the absurd is born out of the confrontation between the human need and the unreasonable silence of the world. I love that statement. It brought me back to how I, we, they, are all talking too much about whatever—Buddhism. And I keep coming back to my favorite line from Shakespeare: “The rest is silence.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.