Tantric or esoteric Buddhism is one of the great forms of Buddhist tradition. In the West, it is usually associated with Tibet, where tantric Buddhism has flourished for more than a millennium. Meanwhile—although it is approximately as old as Tibetan forms and has held major cultural and religious significance—the tantric tradition of Japan is comparatively little known in the West. This stems in part from the fact that the primary traditional forms of Japanese Buddhist tantra (Shingon and Tendai) have not made strong efforts to spread their denominations outside of Japan.

Japanese Buddhism experienced significant changes in the 20th century as the country modernized, fought a war with the West, was occupied by the United States, and developed into an urbanized technological society. Many new Buddhist movements appeared, including the group known as Shinnyo-en (“Garden of Absolute Reality”), founded in 1936. Like most new Buddhist movements, Shinnyo-en draws on multiple sources, but it is most directly connected to the Shingon tradition as practiced at Daigoji, a massive temple complex and pilgrimage site in southern Kyoto. Because it has a strong lay focus, Shinnyo-en has been able to grow quickly and establish practice groups throughout Japan, Asia, and in the West. Thus it is helping to bring more Western attention to the ancient tantric traditions of Japan.

Along with its tantric connections, one of the distinctive features of Shinnyo-en is its focus on the Mahaparinirvana Sutra (also called the Nirvana Sutra), one of the central works of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition. This text purports to record the final sermon of the Buddha before he passed away into final nirvana. The sutra deals with many issues important to the development of Mahayana thought and practice, but it is especially noted for its teachings on buddhanature. In part because it teaches that all beings without exception have the capacity to reach complete buddhahood, it has been treasured in East Asia and inspired reformers such as Dogen, Shinran, and Nichiren. This is true in modern times as well, as the followers of Shinnyo-en rely on this sutra for guidance in the chaotic contemporary world.

The following interview took place in New York this past summer, when Tricycle editors James Shaheen and Philip Ryan sat down with Shinso Ito, who was in town to speak at a conference. Shinso Ito is the current head of Shinnyo-en and the daughter of Shinnyo-en cofounders Shinjo and Tomoji Ito. The interview provided a chance to learn more about this growing Buddhist movement, particularly its approaches to the practices of engaged Buddhism and meditation.

—Jeff Wilson

Why is volunteerism and other social work so central to Shinnyo Buddhism’s practice? Master Shinjo understood that the training within the traditional Buddhist framework would lead to one’s own enlightenment as a monk, but he believed religion had to be able to help more people, including those who were not especially religious, in ways that suit their different circumstances. He incorporated new practices such as volunteerism so our sangha [community] could offer assistance to the widest range of people. People who are interested in traditional Buddhist training are always welcome, but volunteer activities provide an additional avenue for Shinnyo-en to contribute to the wider secular community. Since we are a lay-oriented form of Buddhism, we believe it’s very important to engage with the community around us and to express our ideals there selflessly and unconditionally. I think that is pretty common in other religious traditions, too. For us in Shinnyo-en, though, it’s a way to extend the Buddha’s lovingkindness and compassion, something we believe is innate in all of us. And that benefits both the receiver and the giver. For the receiver, the benefit is obvious. For the giver, it cultivates a stronger sense of compassion for the suffering of every living being. But it has to take concrete form. We have to actually do something physically.

At the organizational level, we can do things by donating the money we raise to various charities and working in harmony with other groups. But when we’re engaged at the individual level, it’s an opportunity to experience the joys of selfless service and attain the accompanying insights. For example, we realize our heart’s natural capacity for compassion, which is very liberating in and of itself.

There is the story of Chudapanthaka from various Buddhist sources. Basically, it’s the story of one of the Buddha’s monks who cleaned or swept his way to enlightenment. Chudapanthaka became an arhat[enlightened one] not because of his intellect—he was considered dumb or “slow” and couldn’t memorize any of the Buddha’s teachings—but because of his focused effort, or “one-pointed mind,” to clean; through that, he was able to see the true nature of existence.

True, selfless service, or true volunteering in the Buddhist sense, must contain this element of one-pointedness for it to lead to an authentic experience of the Buddha’s enlightenment. In Shinnyo Buddhism we sometimes describe it as “unconditional” service to others, something you engage in without attachment and without expectation of reward or recognition. The spiritual growth you experience is validated and confirmed by the sangha, and paradoxically, it lifts your idealistic aspirations for enlightenment to a new level by placing them within the context of everyday reality.

Another way to look at it is to say that selfless service brings balance to your practice. Since it engages the body, it balances the tendency we have to think and theorize rather than act. By channeling your energy into acts of service, you transform the ideal into the real. So cleaning the inside of a temple, or picking up trash at a public park, not only cleans the space used by others (this is where the selfless part comes in); it figuratively polishes your buddhanature. It’s palpable in the joy and satisfaction you feel.

This is related to the Buddhist concept of building merit. One of our daily chants goes:

May the merit I have accrued be transferred to others, and may

we, all together, follow the Buddha’s path to enlightenment.

This daily chant is an affirmation of our buddhanature, and any kind of sincere, correct practice builds merit, which counteracts and diminishes, or purifies, negative karma. Skillful and meritorious practices work on the deep, unconscious level of the mind, reorienting the psyche toward the boundless lovingkindness, compassion, joy, and equanimity that characterizes your buddhanature. And that’s what liberates us and makes us happy in everyday life, regardless of the external circumstances we may find ourselves in.

The engagement you describe as a practice is increasingly popular among Buddhists here in the United States. Does your school also emphasize meditation? Yes. Along with active engagement with society and volunteerism, meditation is an essential part of our practice. In general, our method of meditation is called sesshin, which means “to touch the heart or essence [of buddhahood]” in Japanese. It is “structured” in the sense that it takes place in one of our temples and is a guided meditation based on the principles of the Mahaparinirvana Sutra and esoteric Buddhist traditions.

Meditation helps people to bring out their inner goodness. We have trained spiritual guides who help people to meditate, to become aware of and “polish” that inner goodness, and to find contentment in life. Through such guided meditation, trainees become aware of things they hadn’t noticed before and discover how to walk the road to happiness.

Do you begin by focusing on the breath or on an object, or is it something else? Meditations are held with practitioners focusing their consciousness after having regulated their breathing and fixed their postures. We do not depend on any particular sitting posture. People have different ways of sitting, which are all OK. You can sit on the floor or in a chair. As we sit, we form the dhyani mudra [the meditation posture in which the right hand rests on the left, palms up, with tips of thumbs touching]. We do this as a figurative expression of the form that the Buddha Shakyamuni took as he sat under the Bodhi tree, calmed his inner mind, focused his consciousness, and then transcended that state of being in order to achieve enlightenment. Skilled practice is required to focus one’s consciousness. First we calm our minds.

Depending on the person, we may reflect on our recent actions or behaviors, or recall positive experiences by recounting the many blessings (both tangible and intangible) received from the world around us. Another point of reflection may be the teachings of our masters on how we can become a bodhisattva, a future buddha.

This process allows you to gradually achieve a more concentrated state of consciousness. As you become more adept at meditation, you can achieve this concentrated state of consciousness through mantras or contemplations in a short period of time. But the willingness to grow spiritually and discover your innate spiritual purity is crucial. The Mahaparinirvana Sutra talks about the experience of nirvana as being very personal, as an experience of your true self.

As you begin to meditate with the motivation to discover your pure and true self, a trained spiritual guide will come and sit facing you to help you bring that out. Through the workings of the spiritual union that takes place at this time, the guide is able to perceive the state of your consciousness. Sometimes the perception is shallow, while at other times it is quite deep or penetrating. Based on these perceptions, the guide then helps you to deepen your meditation by providing insight through either figurative or concrete examples. Through this process, you as the meditator are able to place your consciousness in an objective context by viewing your mind and actions with clarity, as if reflected in a mirror.

Through this guided meditation, you are able to examine yourself in a concrete and effective way. The process of probing into yourself, settling the mind, and concentrating becomes easier. Through this process, the path to awakening becomes clearer. In short, you leave the meditation with specific advice and objective insight into your karma or, more simply put, into what you can do to become happier.

Is this guide a friend? This person usually doesn’t know who you are or anything about you but is also meditating along with you and for your sake. He or she is able to discern something when sitting in front of you and conveys whatever that is to you. Many Buddhist sources, including the Mahaparinirvana Sutra, talk about this kind of special ability to guide others as being a natural result of Buddhist training.

In any case, the words conveyed to you will allow you to gain more insight into yourself and better see the attachments and false views that create suffering and hinder your happiness—in other words, how your thoughts and actions affect your contentment and well-being.

As a practice, it guides you to see things in your life from the perspective of a buddha. As you begin to mindfully apply what you learn through meditation, you gradually begin to uncover the Buddha—the awakened being—within you. We think of this as part two of the meditation experience, or the way to carry over your meditation into daily life so that you naturally get into the habit of reflecting on things occurring around you. You use daily life as your place of “sitting,” and for an advanced practitioner, that informal, unstructured type of ongoing meditation becomes the primary means of gaining insight.

So the aim is to realize the buddhanature, to recognize the buddhanature within oneself? That is correct. Among all the different forms of life and creatures great and small, we were born as human beings. As such, we are innately endowed with goodness and the consciousness to use it for others. It’s in our very nature as human beings to want to use that goodness for the sake of others, to be of help and service. So I want the people training themselves in Shinnyo Buddhism to be confident that they can offer something to the world, because that is how we can find true happiness and help others become happier, too.

What was it specifically in the Mahaparinirvana Sutra that your father saw that could bring Buddhism to everyone? The Mahaparinirvana Sutra is important in many ways, but we consider the following three points to be particularly significant. First, the Tathagata, the enlightened Buddha, lives on in the teachings of the sutra; second, we can all find a way out of samsara [cyclic existence or the world of suffering] to enlightenment, because we all have a buddhanature; and third, when you live your daily life with the same heart and mind as a buddha, your life will be full of joy. This is possible for both the renunciant and the layperson, whether one is male or female. These are the points Master Shinjo paid special attention to when he was establishing Shinnyo Buddhism, building on the Shingon tradition to which he became a successor.

The Buddha was born as a prince of the Shakya clan, but he left his princely life to meditate and devote himself to training. Eventually, he left many teachings to us. Among the many sutras that contain the Buddha’s teachings, Master Shinjo saw incomparable wisdom in the Mahaparinirvana Sutra, and thought excitedly, “This is it! This is what I’ve been looking for!” Master Shinjo felt the teachings in the sutra were the perfect doctrinal tool to emphasize lay practice and the idea that all people have the potential to attain unsurpassed enlightenment. For example, Chunda, the humble blacksmith, is a central figure in the sutra and is praised by the Buddha as an example of a householder who could continue living and working in society yet attain the highest enlightenment, thanks to the virtue of his sincere altruistic practice. In short, the sutra spoke to his original aspiration and calling to help people from all walks of life find true liberation.

First and foremost, our movement exists to provide a path to spiritual liberation for lay practitioners. However, to make sure it survives intact as a religious tradition, we also need to have leaders who undergo rigorous priestly training and dedicate themselves to facilitating people’s journey along that path.

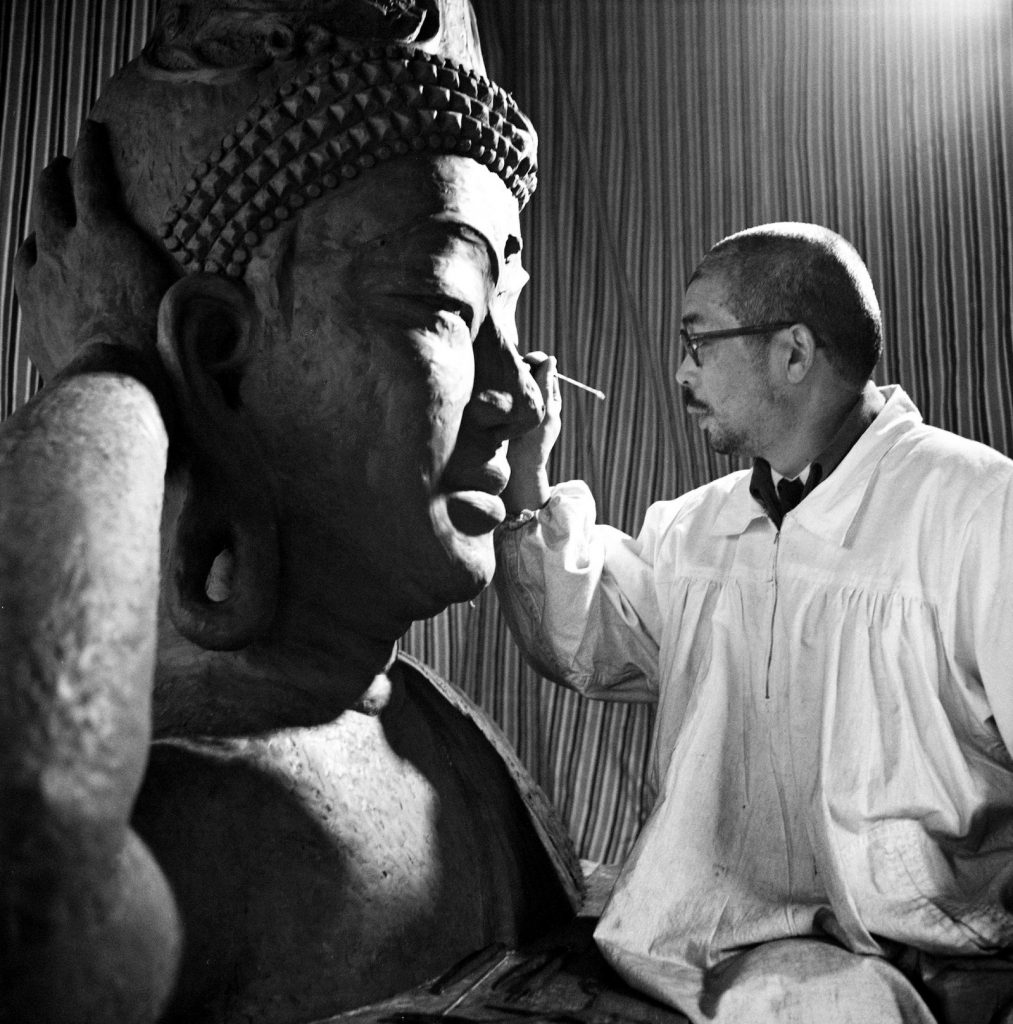

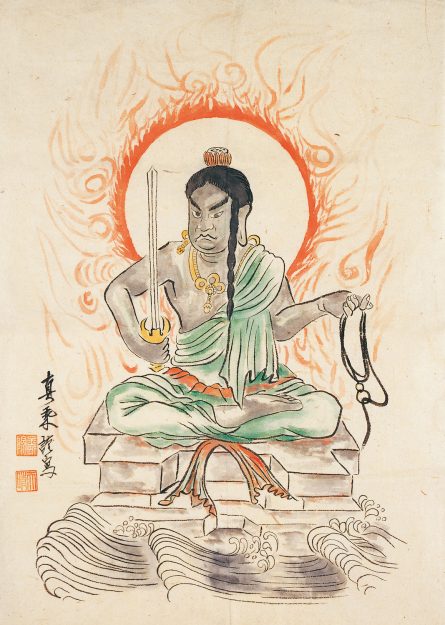

Master Shinjo was a prolific sculptor. How does his work facilitate that journey? Master Shinjo wanted us to understand that his sculpted buddhas represent what already exists inside you, the viewer. His Buddha images reflect the buddhanature that manifests differently in different people, so he created images of various buddhas. He wanted to teach people about their own goodness—that the buddhas you may have enshrined, the ones you like, or the ones you are drawn to, are the buddhas representing the qualities of buddhahood in your own heart.

These are especially difficult and confusing times. What opportunities do you see in this? The challenges can be taken as opportunities to polish one’s mind. I don’t want people’s minds to lean toward negativity. Rather, I hope that they will use this difficult time as an opportunity to acquire the strength to sustain a positive attitude at all times.

Young people are vulnerable to negativity, which could shape their future irrevocably. They often don’t know where to look for meaning and can easily take a wrong turn. I want to encourage young people, communicate and interact with them, and help them keep their hearts and minds pure and open—I believe there are ways for an individual to do that, even in times of difficulty. I want to help them see the value of working on themselves and developing spiritually. For example, if we take a crisis, even one that may seem far off, and use it to meditate and reflect and gain some insight based on that, and then apply that insight in daily life, we can make some truly transformative changes in our lives. And positive transformation is usually incremental. Small efforts, if concrete, will pile up and bring about big personal, and even social, change.

That’s part of seeing things with the eyes of the Buddha, beyond distinctions and dualities, which helps us to see the real nature of things, the true nature of existence. This is very liberating, as it allows us to let go of the idea that things are permanent, that things will always remain a certain way, or that there are differences between us, all of which prevent us from seeing the big picture—that we are ultimately free, interconnected, and of the same essence.

Buddhist doctrine discusses concepts like the Three Poisons [anger, greed, and delusion], with delusive desire being one of them. It’s easy to learn about them and agree, but it would be a mistake to think that you’ve freed yourself of their pull just because you’ve learned the concept. The practice—the challenge—lies in finding a way to apply that principle or doctrine to the reality of your life. This is where your sangha and teachers can help you to take a big concept like the Three Poisons and link it to the small things. In Shinnyo Buddhism, we think of society as our monastery, our primary training center, and so we stress reflection in daily life. Gratitude. Consideration for others. Putting yourself in other people’s shoes. We try to learn to find fulfillment everywhere. We practice being grateful for the small things we have. As a Buddhist, this is what I want to say. My responsibility as a teacher is to nurture other teachers who can pass on this wisdom and path to others so that humanity—one person at a time—can find the liberation and happiness that we all seek.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.