Just inside the gate to the grounds of Spirit Rock Meditation Center, in Woodacre, California, stands a modest “gratitude hut.” It honors teachers past and present who have inspired the inclusive style of this Vipassana retreat center nestled in the hills forty minutes north of San Francisco, in Marin County. Pictures of Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike paper the walls: the current Dalai Lama, Sri Ramana Maharshi, Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj, Sayagyi U Ba Khin, Maha Ghosananda, Anagarika Munindra, Thich Nhat Hanh, Kalu Rinpoche—to name a few—along with some of today’s most well-known Vipassana teachers. The center’s leading figure and cofounder, Jack Kornfield, draws freely from a broad range of spiritual traditions, citing teachers, political leaders, poets, writers, and artists in what he describes as an effort to speak to people using the language and metaphors they know best.

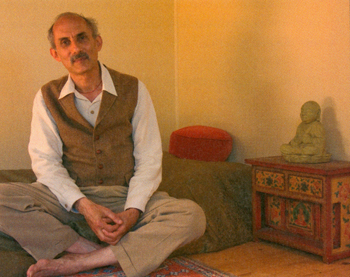

Tricycle caught up with Kornfield on a mid-afternoon in March, in a room used by teachers to interview students. Typical of the center, the room affords an incomparable view of the hills and valleys beyond. Kornfield has taken a break from leading a silent retreat and sits relaxed, casual, and ready to talk. His latest book, The Wise Heart: A Guide to the Universal Teachings of Buddhist Psychology, has just been published.

What do you hope people will learn from your latest book? Two things: The first is that Buddhism as a psychology has a great deal to offer the West. It provides an enormous and liberating map of the human psyche and of human possibility. Second, Buddhism offers a holistic approach. Often people say, “This part of life is spiritual, that part worldly,” as if the two can be divided. My own teacher, Ajahn Chah, never made a distinction between the pain of divorce and the pain in your knee and the pain of clinging to self. They are all forms of suffering, and Buddhism addresses them all.

One aspect of the Buddhist approach to psychology you call, “behaviorism with heart.” Can you explain what you mean? Western behaviorism grew out of rational emotive therapy, in which thought substitution—good for bad—and retraining an individual to establish healthy habits of mind were central. In behaviorism with heart, the Buddha instructs us to see that certain thoughts we have about ourselves or others are not compassionate. Through specific Buddhist trainings, like metta practice—a meditation in which we cultivate positive mind states toward ourselves and others—we can learn to release negative thoughts and replace them with positive ones. Where Western psychiatry has focused largely on mental illness, Buddhism focuses on the cultivation of a healthy state of mind through mindfulness, training in compassion, and so on.

You believe in the fundamentally compassionate nature of the human heart. In our own Western tradition this has been debated for centuries. Saint Augustine wrote, “If babies are innocent, it is not for lack of will to do harm, but for lack of strength.” Wordsworth, on the other hand, wrote, “Heaven lies about us in our infancy!/Shades of the prison-house begin to close/Upon the growing Boy.” Buddhists differ here as well. Is Buddhist practice a question of cultivation or allowing our “pure nature” to manifest? We can view our nature as being defiled and deluded, as Augustine might point out. Or we can view our nature as compassionate and loving. So then maybe we should add an “s” and talk about our “natures.” I believe it is most skillful to try to get people to focus on and cultivate the positive. In the Theravada sutras, the Buddha describes the nature of mind this way, “Luminous is the mind, brightly shining is its nature, but it is colored by the attachments that visit it.” [AN 1.49-51] I’ve found that pointing people to their fundamental goodness will awaken it. It’s more skillful than pointing to the negative. We are so loyal to our suffering and to seeing ourselves as damaged that it’s very easy to use spiritual practice to reinforce our self-judgment. That doesn’t help people become liberated.

In your book you point out that Buddhist psychology is not especially focused on the interaction between student and teacher. In Western psychology, the therapist-client relationship is central. Can you say something about this distinction? Of course the relationship between the student and teacher is important, and teacher-student contact is essential. But that’s only one part of it. Even more important are the inner practices, where much of the real transformation comes about. The root of Buddhist understanding of mind is that the mind can be trained and awakened to the nature of reality. Through training and practice we discover our true nature and find liberation. So this is a very different approach from focusing on two people sitting in a room together talking. You do the trainings your teacher offers, and through them you learn to transform and awaken yourself. This is what happens on our retreats.

You talk about the content of our stories—whether it’s the details of our personal histories or just what’s going on right now. In Buddhist psychology, how important is it to understand those contents and to what extent do they become a trap? Content can be a trap, and ignoring content can also be a trap. So one of my tasks as a teacher is to listen to both. There’s a great freedom in just being aware of thought and seeing that it’s empty. But when somebody says, “I think all the time,” I’ll ask, “What do you think about?” If they answer, “My son just died six months ago,” I might ask, “How do you work with grief?” Or if they say, “I’ve just inherited $4 million,” I might ask, “How do you work with planning and attachment?” So sometimes it’s helpful to know the content, and sometimes you don’t need to. When you see the content of thought, it’s not in order to rework it, it’s in order to see the whole pattern so that you can become free.

You claim that Buddhist psychology goes further than Western methods do. For instance, you write of the Three Poisons (anger, greed, and delusion) that “we reach below the very synapses and cells to free ourselves from the grasp of these instinctive forces.” Do you mean to say that greed, anger, and delusion are dealt with once and for all? If our goal is, as has sometimes been said in the Western psychological tradition, to reach an ordinary level of neurosis, then the goal of Buddhist practice takes us far beyond that. It is to free us from neurosis or to shift identity so that we are no longer subject to those forces in an ordinary way; we are liberated from the power of those forces. And the fact that this is possible for us as human beings is tremendously good news.

In your terms, nirvana is the Buddhist definition of mental health, the optimum goal of Buddhist psychology. You say that Westerners sometimes misunderstand nirvana as a transcendent state—I now refer to your previous book After the Ecstasy, the Laundry—but are you selling nirvana short by giving it such a mundane cast? When we’re idealistic, we—and many practitioners in Asian Buddhist countries as well—imagine that nirvana exists somewhere high in the Himalayas, reserved for monks who have meditated for the whole of their life. My own teachers—and other wonderful masters like Shunryu Suzuki Roshi—emphasize that nirvana is to be found here and now.

In the morning and evening chanting in the forest monastery we recite the Buddha’s words, that the dharma of liberation is ever present, immediate, timeless, to be experienced here and now by all who see wisely. Nirvana appears when we let go, when we live in the reality of the present. Sorrow arises when the mind and heart are caught in greed, hatred, and delusion. Nirvana appears in their absence. Nirvana manifests as ease, as love, as connectedness, as generosity, as clarity, as unshakable freedom. This isn’t watering down nirvana. This is the reality of liberation that we can experience, sometimes in a moment and sometimes in transformative ways that change our entire life.

So these moments in which we experience freedom from anger, greed, delusion—these, too, are nirvana? They are what my teacher Ajahn Buddhadasa called “everyday nirvana.” They are tastes of nirvana resting in awareness, the reality of the liberated heart and mind. He said, “There’s no difference between the absence of greed, hatred, and delusion for a moment or for a lifetime.” This is not an esoteric notion of nirvana, that it is someplace far away to be attained only after a long time. Nirvana is to be known here and now. Sometimes we experience this through profound meditation, other times through the simple direct opening to freedom.

Do you think it’s possible at some point in a person’s life that this experience of nirvana becomes complete—that one does not return to his or her earlier life or states of mind? Certain people describe their experience that way; others who also seem deeply enlightened say not. But liberation is only found here and now, the direct experience of freedom, beyond the concepts of nirvana or enlightenment. In our life, we can actually experience what the Buddha taught: suffering, the cause of the suffering, and the release of suffering. This is a direct and immediate experience, and the cessation of suffering is the experience of nirvana.

I explain these teachings as “The Nature of Enlightenments”—there are a number of ways to experience nirvana. Nirvana can be experienced as emptiness, as the void. It can be experienced as the absence of greed, hatred, and delusion. It can be experienced as silence, as pure awareness, as peace, as wisdom, as boundless love and as true stability. It has a number of different dimensions, like facets of crystal.

How, then, does traditional therapy fit into your teaching model? Western psychology also has skillful means to help us practice the Four Noble Truths: suffering, its causes, its end, and the means to that end. The best of Western psychotherapy is like a paired meditation: If you have a wise therapist, they can help you pay attention with compassion and mindfulness to difficulties that may not come up as you sit by yourself, or help you with past traumas that are too difficult to handle on your own because the trauma is too great. A wise therapist can assist you to practice in areas where sitting in meditation alone may not suffice. There’s tremendous value in some of the Western clinical tradition, and it can help you to know suffering, its causes, and find release.

You outline twenty-six principles that you call universal to Buddhism. Yet the different Buddhist traditions are fraught with contradictions, and some scholars find, say, the Mahayana and Theravada worldviews incompatible. One way some Mahayanists have dealt with this is to divide schools into “higher” teachings and “lower” teachings, setting up a kind of progression. But you seem to have no problem lifting from the Mahayana tradition—and many others to boot. Mystics and true practitioners don’t look at liberation from a scholastic point of view, but rather from the point of view of inner realization. And for the mystics of each of the great Buddhist traditions these same common elements exist and are expressed. There is almost nothing that I can find in the Mahayana or the Vajrayana or the Pure Land that isn’t also found in its root form in the Theravada. Within Theravada Buddhism there are teachings of what Vajrayana might call Dzogchen or Mahamudra and Buddha-nature. They’re found within every tradition. My own teachers from the forests of Thailand, for instance, talked about the original mind or original nature, jit derm in Thai. While this is a common Mahayana concept, it’s also the direct experience of Theraveda monks. Likewise, my teacher Ajahn Chah and his lineage of Theravada forest monks talk about the unborn nature of consciousness, and I’ve heard these same teachings from Tibetan lamas.

What did Ajahn Chah mean by original mind; is it the same as Buddha-nature? Yes, definitely. Ajahn Chah describes, “The original heart-mind shines like pure, clear water with the sweetest taste. To know this we must go beyond self and no-self, birth, and death. This original mind is limitless, untouchable, beyond all opposites and all creations.” This is his description of Buddha-nature. He goes on, “When we see with the eye of wisdom, we know that the Buddha is timeless, unborn, unrelated to anybody or any history. The Buddha is the ground of all being, the realization of the truth of the unmoving mind. So the Buddha was not enlightened in India. In fact, he was never enlightened and was never born and never died, and this timeless Buddha is our true home, our abiding place.” The scholars tend to argue. The mystics look at each other and smile.

Traveling in Palestine and Israel recently, I was with this great mystic—a Hasidic rabbi—who said, “I’ve been reading about Buddhism. Tell me first about luminosity of consciousness,” and we talked about that. “Now tell me about the void.” And I said, “Well, there are different ways you can experience the void.” And he was so excited. He said, “Oh yeah, we have them too. And this is how our luminosity appears in our Hasidic practice.”

Do you see the Buddha as a mystic, then? Absolutely. By mystic I mean one who looks profoundly into the nature of reality. The Buddha didn’t take the teachings of anyone and simply copy them. He looked deeply and had this extraordinary vision of the nature of consciousness and how beings arise and pass away and what brings us to freedom.

You draw from multiple traditions in your teachings. Your book is full of quotes from people outside of the Buddhist tradition—Mother Teresa, the popular American poet Mary Oliver, Jewish, Muslim, Christian, and Hindu sages, and so on. You even turn to a non-Buddhist, Sri Nisargadatta, to describe emptiness. Why is that? I believe that dharma is universal, and when Mary Oliver expresses the dharma of impermanence in a poem about a butterfly, and the ancient Zen master Ryokan expresses the dharma of impermanence in a poem about young bamboo, they’re both teaching the same dharma. I use whatever expressions best help to awaken us.

The dharma of liberation is ever-present, immediate, timeless, to be experienced here and now.

So in other words, you would see using material people are familiar with as a skillful means to teach the dharma? Yes. I also use the language of science, because one of the beautiful things about both Buddhist psychology and Western science is that they are both experiential and they both undertake to study experience as it happens and to record it and to replicate it. There’s a lot of commonality.

Where do science and Buddhism part, then? In the opening page of my book, I quote the Dalai Lama: “Buddhism is not a religion. It is a science of mind.” But again, there isn’t one Buddhism. Buddhism also functions as a religion for many people—there’s devotion, religious rites and rituals, cosmology. In this way it functions as other religions do. But when you go back to the fundamental teachings, the Buddha’s main focus was much more a science of mind: here is how the mind works, and this is how you liberate the mind and the heart from suffering, through compassion and generosity and the practice of meditation.

So it’s very phenomenological? Absolutely.

What happened, then? How did it become a religion? I can’t say I know, but in the Asian Buddhist cultures where I lived, Buddhism seems to function as both a religion and a science. There are some people who are primarily devotional by nature. They find enormous support and solace in prayers to the Buddha, by making offerings, by faith. There’s also another group that wants to do the practices of inner transformation in a systematic way, as the Buddha taught. Both are ways to meet the needs of humanity.

Different teachings for different temperaments? That’s a much simpler way to say it.

How is Buddhism different from the many traditions you draw from? For instance, as a Christian or Muslim you may think you have a soul. As a Hindu you may understand atman as a universal principle. You bring these teachings into your own teachings, but what is distinctive about Buddhism? There are many forms of Buddhism, but in its essence, Buddhism has a tremendously clear and systematic way to put into practice and experience the wonderful principles we learn in many religious traditions. Christ speaks about turning the other cheek; Muhammad talks about the compassion of Allah. But within Buddhism there are methods that teach you how to develop and practice these principles. There are systematic trainings in compassion and forgiveness, for example. Buddhism also has a unique emphasis on selflessness. It places no emphasis on a creator god, so the emphasis is on our direct experience of liberation, not on the adopting of an external faith.

Would you fall into the camp of thinking that fundamentally all of these traditions are talking about the same thing or hoping for the same goal? I wouldn’t go that far. All of the mystical traditions of Christianity and Judaism and Hinduism and so forth are trying to open us from the small sense of self to some greater reality. The ways that they do so may lead us to different experiences. In many cases, there are really strong parallels, but not always.

There are many skillful means. Even within Buddhist lineages, between one Tibetan master and another, there are differences. They may say, “I’ve got a slightly different—and better—way to get you to freedom.” But they are all a part of the great mandala of awakening, skillful means.

You’ve said that most American Vipassana teachers draw copiously from other traditions. And have practiced in other traditions, sometimes quite deeply, yes.

Why are they more likely than others—say, more traditional teachers or monastics—to do that? It’s harder for monastics to go outside of their tradition because their vows and their way of life prevent it. With vows you’re dedicated to your monastery and to your lineage, in a very beautiful way. There is a lot less opportunity than a lay teacher would have to practice in other traditions.

Now in the West we have the riches of all traditions translated into English. We’ve got Tibetan lamas and Sufis and Hindu gurus and Hasidim visiting Richmond, Virginia, and Kansas City, Missouri, to teach. In our own community some of our greatest teachers from Burma, India, and Thailand have come to our centers. Before they returned to Asia, they blessed us and said, “Now it’s up to you.” They gave us a freedom to find skillful languages, skillful means, and also to draw on other languages or teachings that were complementary.

My own teacher, Ajahn Chah, told me, “What’s important are not the words of the dharma but teaching the way that people can free themselves, so that they learn compassion and generosity and liberation. If you do better calling that Christianity, call it Christianity. Call it whatever you need to call it. The words aren’t important.”

EXTRA

Sitting in the Dark

An excerpt from Jack Kornfield’s new book, The Wise Heart.

Sometimes we forget that the Buddha too had fears: “How would it be if in the dark of the month, with no moon, I were to enter the most strange and frightening places, near combs and in the thick of the forest, that I might come to understand fear and terror. And doing so, a wild animal would approach or the wind rustle the leaves and I would think, Perhaps the fear and terror now comes. And being resolved to dispel the bold of that fear and terror, I remained in whatever posture it arose, sitting or standing, walking or lying down. I did not change until I had faced that fear and terror in that very posture, until I was free of its hold upon me …. And having this thought, I did so. By facing the fear and terror I became free.”

In the traditional training at Ajahn Chah’s forest monastery, we were sent to sit alone in the forest at night practicing the meditations on death. Stories of monks who had encountered tigers and other wild animals helped keep us alert. At Ajahn Buddhadasa’s forest monastery we were taught to tap our walking sticks on the paths at night so the snakes would “hear” us and move out of the way. At another monastery, I periodically sat all night at the charnel grounds. Every few weeks a body was brought for cremation. After the lighting of the funeral pyre and the chanting, most people would leave, with only monks remaining to tend the fire in the dark forest. Finally, one monk would be left alone to sit there until dawn, contemplating death. Not everyone did these practices. But I was a young man, looking for initiation, eager to prove myself, so I gravitated toward these difficulties.

As it turned out, sitting in the dark forest with its tigers and snakes was easier than sitting with my inner demons. My insecurity, loneliness, shame, and boredom came up, along with all my frustrations and hurts. Sitting with these took more courage than sitting at the charnel ground. Little by little I learned to face them with mindfulness, to make a clearing within the dark woods of my own heart.

From The Wise Heart: A Guide to the Universal Teachings of Buddhist Psychology © 2008 by Jack Kornfield. Reprinted with the permission of Bantam Dell.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.