It was a high-status job, but only within the bounds of the monastery. In there, if you held the title benji, you were somebody. That’s remarkable in a place where the clothes, the schedule, and most of the forms of daily life were oriented toward everyone being pretty equally nobody. If you were the benji, you had a special seat in the meditation hall, next to the shuso, the head monk. You could be invited to staff meetings. When the Abbot was resident, you might be invited to the elegant tea at his place after morning rituals. You played a significant role in any number of ceremonies. People might cut you a bit of slack with regard to timing, because you had a lot to do. Where the head monk went, you went. You were his or her attendant; you were the benji.

In point of fact, though, you were the garbageman. That’s what people—especially your friends—called you, the garbageman. You dealt with that. There were disgusting aspects to it, of course. If kitchen compost sat too long, or in warm weather, it would stink. The garden crew helped with the containers sometimes, taking them to the garden, sometimes even washing them, sometimes returning them. With its emphasis on precision and tidiness, Zen practice did not lead to, or tolerate, messy garbage areas for very long. Thus the containers in the kitchen, the dorms, the bathrooms, and the other places stayed mostly OK. The contents did have to be sorted. Primarily, this meant into Burnable and Unburnable. Opinions varied about what was burnable. Our monastery sat at the conclusion of a 14-mile-long dirt road through a national wilderness area in central California, and in the 1970s we considered a lot of things burnable. Plastic, for instance.

Smoke rising from the Burnable can could be quite foul, but the garbageman had to stay close to it, vigilant, because, well . . . national wilderness area, 14-mile-dirt road, and a coastal shrub ecology that loved to burn. Fire is and always has been integral to the health of local flora; but lightning and foolish campers started enough of those. A forest fire in the middle of the nowhere we were in would obviously not be good for the monastery.

In cold weather, it felt good to stand by that 50-gallon drum with its crosshatched iron grate lid. It was difficult, though, in the baking sun. No shade could be found, because there was no structure near the Burnable can. It sat raised from the ground on a low, broad concrete platform, in the middle of an open area near the creek. The can was punctured with a square vent at its bottom, to draw air. When Burnables were on fire in there, the only thing nearby was the garbageman with his shovel.

The job was physically demanding. The big Brute containers in the kitchen—they were about hip high, and most of a meter across at the top—did not make their way down and up the back stairs on their own. Someone had to carry them. Same with the knee-high compost buckets. If the gardeners didn’t get them, that was your work.

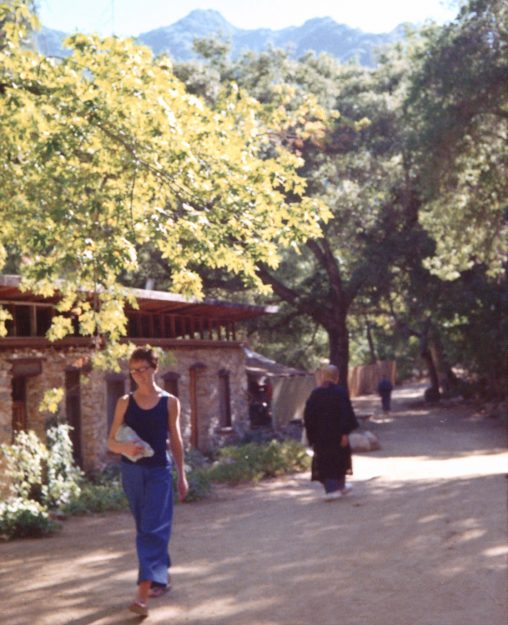

Some benjis before my time, and some who came after, used an old wheezing pickup truck to move the Brute containers around. I didn’t like to. The bed of our pickup was relatively high, which meant more lifting. And there was really only one wide earthen path through the heart of the monastery. It ran up through the middle of the main housing area, across a short bridge, alongside the central buildings—dining room, dorm, kitchen, meditation hall, library—on past the guest housing and the baths and out toward an empty, undeveloped part of the property, where it gave out. My objections to the truck were that it was a loud machine; that there were small children running around; and that we were, after all, living in a monastery. Most of the forms we used, the schedules we followed, and the clothes we wore for meditation dated back to feudal Japan. The truck, more than the small children, seemed out of place.

There was also an alternative: Garden Way carts. These had come onto the market not too long before, part of a blooming desire for high-end gardening merchandise. They worked like wheelbarrows, except that instead of having one low wheel up front, the carts had two large wheels, multi-spoked, like the kind you see on bicycles. This meant they didn’t tip from side to side. Where the hollowed-out metal bed of a wheelbarrow sat, Gardenway carts had a wide, light weight plywood box, open at the back and on top. You could put a lot in there; several Brutes at a time fit perfectly. The wheels turned easily, and the clever design put most of the burden over the axle instead of in the hands and arms of the driver. After loading the Brutes into the carts, transporting them, and unloading them, the garbageman had then to wash them before taking them back. For this last, I used a long-handled brush.

Physical work wasn’t the only thing causing tiredness; there was also the centuries-old Zen skepticism about sleep. The clock ran a little longer than six hours, from the lights-out signal at 9:20 p.m., to the wake-up bell, which began near 3:30 a.m. Some of us had duties that kept us up a little later or required us to get up a bit earlier, but six hours was the baseline. This was perfectly OK in an environment where there was little outside distraction—no phone, no television, no media of any kind, apart from irregular deliveries of paper mail—and a large daily dose of meditation. Still, sleepiness was for everyone just part of monastery life.

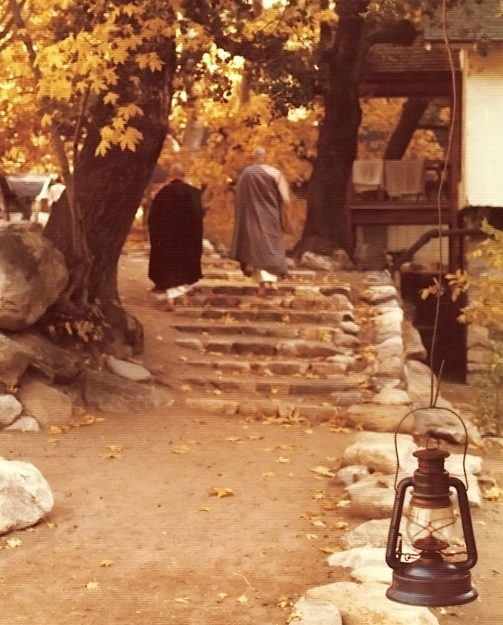

The monastery had two basic seasons, winter and summer. From September through April it focused on traditional Zen monastic training: two three-month practice periods, with a short break in between, and a sesshin—a week-long intensive meditation retreat—at the conclusion of each. Apart from sesshin, the daily schedule generally included five 40-minute periods of zazen, sitting meditation. There was little conversation, and meals were eaten in the zendo (meditation hall) in the formal fashion called oryoki.

The summer months centered around the guest season, which started in late spring. Guests paid quite a bit to be there—away from cities, in nature, with streams, pools, and hot springs they could soak in, and places where they could sun themselves, then dip into water of various temperatures and sun themselves some more. Zen students cooked and served meals for them, prepared and cleaned their cabins, and transported the guests over the single road in and out. Each year, the guest season provided the monastery’s main financial support. There were fewer zazen periods scheduled—four per day instead of five—but given the work load, not every student could make it to every period.

Throughout the year, just having a schedule reduced the anxiety of decision. We very rarely had to worry about a plan for the day, though there were two days out of ten with some unstructured time in them. This allowed for laundry, mending, head shaving, a short hike, or a nap. Exploratory hikes might take us into nature, but we never left the monastery for another place. We fundamentally all did everything at the same time, and in the same way. Meals, bathing, work, study, and religious devotions were all infused with ritual; if the schedule wasn’t exactly restful, it was at least very regular. For someone trying to walk the Buddhist path, it was like training camp. But if you followed the schedule, if you went along with the plan, it all kind of worked.

We often caught up on sleep in the zendo. During meditation. If you had been practicing it for some years, meditation became familiar, the opposite of exotic. The posture, too, could get quite comfortable, especially if you were tidily wrapped up in robes. It was usually dark outside during our sitting times, and the deep mountain valley, draining the hills to the creek outside the zendo, sharpened the bite of the damp and cold. Thus your pillow in the dry, fragrant hall could appear as a kind of sensual refuge. Dim, kerosene lamplight, the slow, mournful gong of temple bells . . . a person could easily drift into a snooze. The classical remedy, dating back centuries, was the stick-carrying hall monitor, the junko.

We took turns in this role, patrolling the zendo for most of the time, most periods, and whacking sleepy meditators back into alertness. It wasn’t brutal. The ritual was polite: the monitor would first lay the flattened end of the stick on a sleeper’s shoulder. That person, when they became aware of it, would bring their palms together, and bow, conveying the message “Ah, thank you for noticing that I’ve been asleep, wasting my time in dreams instead of meditating. Please assist me further by hitting me a good one on each shoulder. Here’s the first shoulder.” The sleepyhead would then present to the monitor a mostly horizontal back and shoulder, bending forward and to the left, then forward and to the right. The monitor would indeed try to hit them a good loud shot on each shoulder, aiming for the area between the shoulder bone and neck. If it was done right, it didn’t hurt. It was loud and startling. It was supposed to release any holding in the upper back, like an instant massage. The sound was supposed to help awaken others.

I seemed to be taking care of everyone’s garbage. . . . It certainly did not feel fair, especially for a high-status position.

It wasn’t always done well; if the junko missed the sweet spot, it hurt. There was risk in it for the junko too: if you hit someone the wrong way, you felt terrible. There was, of course, no talking in the zendo; no excuse, no apology was possible. You both simply bowed to one another again, as the ritual prescribed, and the junko went on down the row. But everyone could hear from the sound of the impact whether the blow had been a clean one or not. Despite the explanation that every sitter—even a sleepy one—was Buddha, and every hall monitor was Manjushri, the bodhisattva of wisdom, carrying a flaming sword that cuts through ignorance; despite deep bows from both parties before and after, it was still a loud public hit, and it brought up a lot. Goodness knows what baggage we were all carrying.

During my eight-month term as benji, I got hit a fair amount. I didn’t mind, mostly because I understood why and couldn’t really do much about it. Once, though, during sesshin, it got frustrating. People still made garbage, and the benji still had to deal with it. In fact, the kitchen may have produced more garbage during sesshin than during the regular practice-period days. The wastebaskets in the bathrooms may have filled up even more quickly. The benji had just as much work as ever but less time to accomplish it. We were all getting less sleep. The brisk meals seemed further apart from one another than they normally did. Thus I was, as we all were, tired and hungry; but I was also bodily worn out from work. I found it impossible to stay awake in meditation. I seemed to be taking care of everyone’s garbage and getting hit more than ever for it. It certainly did not feel fair, especially for a high-status position. I may have let roll a private tear at the injustice.

The incident I want to relate did not take place during sesshin, though for some reason I was out and about on that day, while most other people were either in the zendo or engaged in administration. “Out and about” does not mean what the phrase might imply in town: I was no flaneur strolling for pleasure or window-shopping. I mean only that I was walking, moving in fresh air, relatively unimpeded. Specifically, I was pushing about 80 gallons of human waste, contained in two big Brutes, loaded into a Garden Way cart. The same sociological impulse that brought us Garden Way carts and a retro high-tech approach to ecology had also brought us compost toilets.

The Abbot counted among his large and illustrious circle of friends a couple who were enthusiastic proponents of this movement. At their instance, the Abbot had seen how conditions both at our isolated mountain-valley monastery and at our coastal biodynamic farm were ideal for compost toilet technology. We would be able to diminish the stress on our antiquated septic systems and, eventually, enrich the soils with our purified, composted, organic nutrients. It would take work. The initiative would require patience and a properly isolated location for secondary and even tertiary composting. At the monastery, we certainly had time. We practiced patience. We were surrounded by miles and miles of uninhabited forest. The carpentry crew was constantly building things—an elegant two-seater shed to house compost toilets, for example—so we had a steady supply of sawdust. Sawdust was an essential ingredient.

One summer earlier, the compost-toilet couple had come to the monastery to survey locations, to advise on shed construction, and to provide general education and encouragement. They called what people deposited “a fluff.” There would be a fluff, toilet paper, and a coffee can full of sawdust added by each user. This would go down a chute into one of the large Brutes. Men would send fluid waste down a separate chute; women would let theirs go in with the fluffs. When the Brutes were sufficiently full, they would be switched out for a fresh set and taken away to the composting trenches. These had been dug with a backhoe and were about a meter deep and ten meters long. They were lined on the sides with cinderblock that rose above the ground another meter. Two such trenches ran parallel to one another, the idea being that when the material in trench one had composted long enough—a year?—it would be turned into trench two, where it would compost for another long stretch.

The trenches lay about 300 meters upstream from the monastery’s central buildings, in an area we called The Flats (short for its earlier names, Grasshopper Flats and Rattlesnake Flats.) This broad sandy field, littered with boulders and down wood, was a small alluvial plain bordered on one side by the creek, and on the other side, by a semicircle of steep hills—technically a hogback. We called it the Hogback. It took about 10 minutes to walk out there, longer if you were pushing a loaded cart. The trenches had been discreetly dug neither too close to the water—the creek flowed from there down along one side of the monastery—nor too close to the path that led up to the Founder’s Memorial Stone, on the Hogback.

As benji, I needed to go down below the compost toilet seats to the bricked-in area where the Brutes stood. I had to get them out, close them up, replace them with empties, and drag the full ones up a steep slope to the waiting Garden Way cart. Out at The Flats, I would peel back the layer of black plastic covering the working pile, add new material, cover it by shoveling on dirt, then replace the plastic, securing it with rocks. Obviously, the Brutes and lids needed to be washed. There was a standpipe, providentially located off the trail, about halfway out to The Flats.

As far as I knew, we were not expecting any visitors. I did not know very far, it turned out.

I used the water from the standpipe to wash the hell out of the compost toilet Brutes, scrubbing them with another long-handled brush that I used only for that. I did the lids as well, and left all these things to dry overturned on a pallet by the standpipe, behind some ceanothus bushes. After a few days I’d collect them and store them out of sight by the lower level of the compost toilets. It was an effective system, if a laborious one.

This particular day, I was passing the intersection where the public road ended, meeting the main lane through the monastery in a T. The outer road descended steep hills before arriving at our entrance, which we’d built out with a torii-style gate, a fence, and a little booth, for someone to be in during guest season. Vehicles that did not belong to the monastery mostly stayed outside.

As I proceeded behind the Garden Way cart, I heard the crunch of car tires on the gravel outside the gate. Thinking it might be one of our shop trucks, I set down the cart and went to see who was driving what, and whether they needed any help opening the gate. To my amazement, as I got closer, I saw an ordinary black 4-door sedan out there, rolling to a smoky stop in the dust.

This never happened. It was extremely rare that any car came down that road by accident. It wasn’t much more than a glorified wagon trail: plain dirt, narrow, rutted and ridged and entirely remote. If someone had made it to our torii gate, they had meant to do so. As far as I knew, we were not expecting any visitors. I did not know very far, it turned out.

I watched from inside the fence as a man got out of the car. I recognized him, but felt no great urge to run and greet him. He looked tough, for one thing, and he was reputed to be tough. Shaved head (like mine but different), sunglasses, suit but no tie. This was Jacques Barzaghi, then famous in California as the chief advisor to Governor Jerry Brown. He’d climbed out of the driver’s seat. Which meant that the trim, elegant man now getting out of the back seat, seeming to bristle with intelligence and darting perception, was Governor Brown himself.

So I went out to say hello, and to see how I could be of service. Barzaghi approached. I got distracted from him, from his walking toward me and speaking, by the third person, emerging from the back seat. Her I definitely recognized. The slender, pretty brunette in a silky dress, helped from the car by the Governor, and now shading her eyes against the morning sun, was Linda Ronstadt. The only words that came to mind were “Oh my god.”

Barzaghi said they’d like to see the Abbot. I told him of course, I would run go find him. They did not seem rushed. Like most people who’d come over that road, they appeared content to just stand there on bottom ground—no cliffs or drop-offs in sight. They were simply having a moment, taking in the colors, listening to the big, sudden silence, smelling the sulfur from the hot springs.

I went for help. I had to get word to the Abbot first; if I could, I had to find the guest manager. Outside the guest season, apart from ordering new sheets or doing inventory, there usually wasn’t much for the guest manager to do, until, like now, suddenly there was. We all switched jobs regularly—nearly every practice period—so we were all familiar with them, and we knew who was doing what. But we didn’t always know where to find them. As soon as the right people were informed, I went back to my Garden Way cart. I took a grip on the handle, cast a glance up at the road, and went on with my work. I’m sure that the Governor, his beautiful consort, and Mr. Barzaghi were seen to appropriately. I wouldn’t know. I was out at The Flats, shoveling.

Next morning, though, I had to spend time breaking up and flattening cardboard boxes; these we stacked and bundled and trucked out over the road to recycle. The tenzo (head cook) had told me there was a real mountain of them—an eyesore and fire hazard— out behind the kitchen. So after burning the Burnables, I headed to the area behind the kitchen, stopping for a drink of water by the coffee machine. To my astonishment, there stood Linda Ronstadt, alone, dangling a bag of tea in a cup of hot water. She raised and lowered it in the cup. I got my water.

“Excuse me. I’m so sorry to bother you. I just had to say, to tell you, that I’m a huge fan. Of your music.”

She looked at me with those big eyes. There was eye contact. “Thank you. It’s very sweet of you to say so.”

We nodded. That was it.

By the creek, at the bottom of the valley, in the middle of the mountains, in the National Forest, there was nothing more to say. If there was, I couldn’t think of it.

I heard later from the Abbot’s assistant that Linda Ronstadt liked our location. She’d said that it was the most romantic place she’d ever been; she’d said, in fact, that a person could fall in love there with Attila the Hun. My estimation of the Governor rose. I didn’t know about Attila, but as I staggered off to do the boxes my heart was pounding, my eyes were misting up and out of focus, and I was having trouble breathing. I was exhibiting all the symptoms.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.