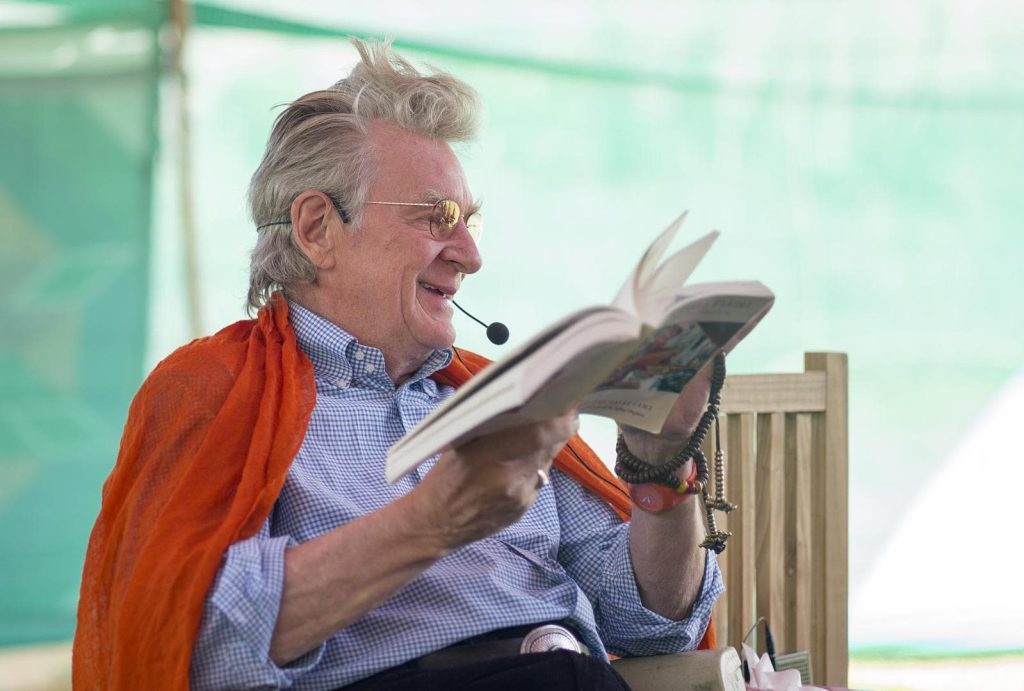

The first American to have been ordained a Tibetan Buddhist monk, Robert A.F. Thurman, Ph.D., has been a personal friend of the Dalai Lama for over 40 years.

The New York Times has recognized him as “the leading American expert on Tibetan Buddhism” and Time magazine named him as one of the “25 Most Influential Americans.” He is co-founder and president of Tibet House U.S., a non-profit organization dedicated to the preservation and promotion of Tibetan culture and civilization, and is president of the American Institute of Buddhist Studies.

Dr. Thurman has translated many Sanskrit and Tibetan Buddhist texts, and is the author of 16 books on Tibet, Buddhism, art, politics and culture. He earned a Ph.D. from Harvard in Sanskrit Indian Studies, taught at Amherst College, and is now a professor of Indo-Tibetan Buddhist Studies at Columbia University.

Dr. Thurman and I spoke on August 14, 2010, at Menla, which also is known as The Land of the Healing Buddha, as one of the Dalai Lama’s Tibetan medicine healing centers. In a verdant valley setting—where the Dalai Lama says he had had his best night’s sleep outside of Dharamsala—Dr. Thurman and psychiatrist/author Mark Epstein, M.D. were conducting their popular summer workshop “Integrating Buddhism and Psychotherapy.”

Can you talk about the difference between a guru in some spiritual traditions and a “spiritual friend” in the Tibetan tradition?

In most levels of Buddhism the authority of the teacher is de-emphasized because the burden is on the students to find things out for themselves. So the basic model of the spiritual teacher is that of a virtuous friend or an auspicious friend, one who brings you good luck, and by giving teachings helps you gain knowledge and experience. As a friend, he or she helps you on your way, but you still have to do it.

It is important to remember the patriarchal context of Indian society. In traditional Indian knowledge fields the guru is a big authority figure, like a father figure, while there is a de-emphasizing of the father figure in most levels of Buddhism. In monastic Buddhism, the abbot is not a big boss and obedience is not a big virtue for the Buddhist monk or mendicant. In the Mahayana tradition, the spiritual friend is a teacher emphasizing how you have to get out there and do your own bodhisattva deeds and become a Buddha.

But in the Tantric and esoteric teachings, the guru figure, which in Tibetan is translated as the “Lama,” is brought back into play. In Tantra you’re dealing with the unconscious; therefore you need someone upon whom to project different things to help you work out new relationships, like you do in psychotherapy. Also, there’s the initiatory practice of seeing the guru as the living embodiment of the Buddha when the teachings are transmitted to you. The Tibetans have a proverb: “The best guru is one who lives at least three valleys away,” which means you receive the teaching and some initiatory consecration—and then you don’t hang out with that person to see how ordinary they are!

Let me jump to what you might like to say to Western psychotherapists. Would you have any general comments on what you think they—we—are doing wrong or are missing?

My general comment would be that I hope they resist the temptation or pressure—and I’m sure most of them do, actually—to define sanity and insanity in terms of today’s society. The ancient Buddhist understanding is that the worldly person is insane from the point of view of the spiritual person, while the spiritual person is considered to be insane by the worldly person.

The worldly person lives for the purpose of this life. They want to get everything out of it: belonging to society, making money, getting fame, and having relationships. That’s really what they’re living for. But the spiritual person is seeking to become an infinite being—in the theistic tradition, becoming one with the divine, and in the Buddhist tradition, becoming a Buddha. For spiritual people worldly success is defined in a different way: this life is seen as an evolutionary opportunity for them to evolve toward becoming an infinite being. Therefore they are not that interested in the goals of status and success within the context of this life.

How this applies to people who do psychotherapy is that perhaps they should think twice about whether whatever is unusual about the client and whatever might be thought of as deranged or neurotic might actually be used to that person’s spiritual advantage. I would encourage therapists to not think of their job merely as re-socializing a person into a society that is really quite insane—a society that pollutes and destroys the Earth, that focuses on money and fame, and that thinks there is no future existence, no future life, no heaven or hell, and “when you’re dead you’re just dead.”

How can Buddhism and psychotherapy complement one another, especially in a non-Buddhist country like the United States?

I used to say when giving lectures to Buddhist groups that if people became enlightened in following the practices of Buddhism that they should combine their study of it with the study of psychotherapy and psychology. Because the best livelihood in this society for someone who is a little enlightened is to be a healer and a psychotherapist. This way they can help people within a framework that is understood here. Otherwise they go back to do something that has nothing to do with sharing their enlightenment, or they try to become a professional guru—and that has terrible problems associated with it.

Being a “guru” is not really institutionalized in our society. It is something weird, and when people try to become professional gurus here they are tempted to play guru games and do all kinds of dumb things. They might go around thinking they are enlightened or pretending that they are, and it’s very hard for them. I’ve often told gurus and lamas that while they are training their students for enlightenment, that they can be building toward a livelihood where that enlightenment can be wielded altruistically for others in a socially accepted and understandable way.

In a way, psychotherapists may wish to consider themselves the vanguard of a new kind of society—a society that truly does value its individuals, where one individual’s development of psychological integration, compassion, emotional expansion, wisdom and insight to the nature of reality is the purpose of the whole shooting match.

To end, I’d like to ask you about a quote from renowned Canadian novelist and poet Margaret Atwood that goes back to your suggestions about positive psychology and increasing our capacity for growth. She said “the Eskimos have 52 names for snow because it was important to them: there ought to be as many for love.”

I think that’s absolutely true. There’s a wonderful passage in the Vimalakirti sutra where he talks about the love of the bodhisattva and the love of the Buddha. To have perfect love, you actually have to be perfectly happy yourself; you have to be happy, since love is what wills the happiness of the beloved. If you don’t know yourself what happiness is, then how can you really be willing their happiness? You may be willing them to do something that you think might make them happy, but that won’t necessarily be what does make them happy.

When you have a reliable type of inner bliss awareness—a sense of connectedness to the universe where you feel the bliss of life flowing up and bubbling up within you—then you want others to have that. And that naturally overflows in the love that wants the beloved to be happy, because you realize that happiness is everyone’s birthright. If you are really blissed-out like a Buddha, you see the bliss in the very cells of the beloved and you realize it’s trapped by their own experience, by some notion that they have—that bliss is not theirs, or that they don’t have it. So your whole drive becomes to try to help them remove the blinders that have been placed on them by their experience, by their fear, by their culture, by whatever notions they have that have not allowed them to feel unreasoned and unreasonable bliss, and then you do whatever it takes to free them.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.