It’s 9:40 a.m. on a crisp Thursday morning at the University of New Hampshire. Students in Associate Professor Kevin Healey’s contemplative media studies class are asked to turn off their phones and walk deep into the school’s College Woods and get lost. “I tell them that I hope they get lost,” Healey half-jokingly says. Before entering the woods, students are handed an envelope with instructions to find a place far enough away from the main campus that could feel like anywhere. Then, settle in. “Be in the space,” the instructions read. “Remember in-class discussions and readings about detoxing and the benefits of reconnecting with nature.”

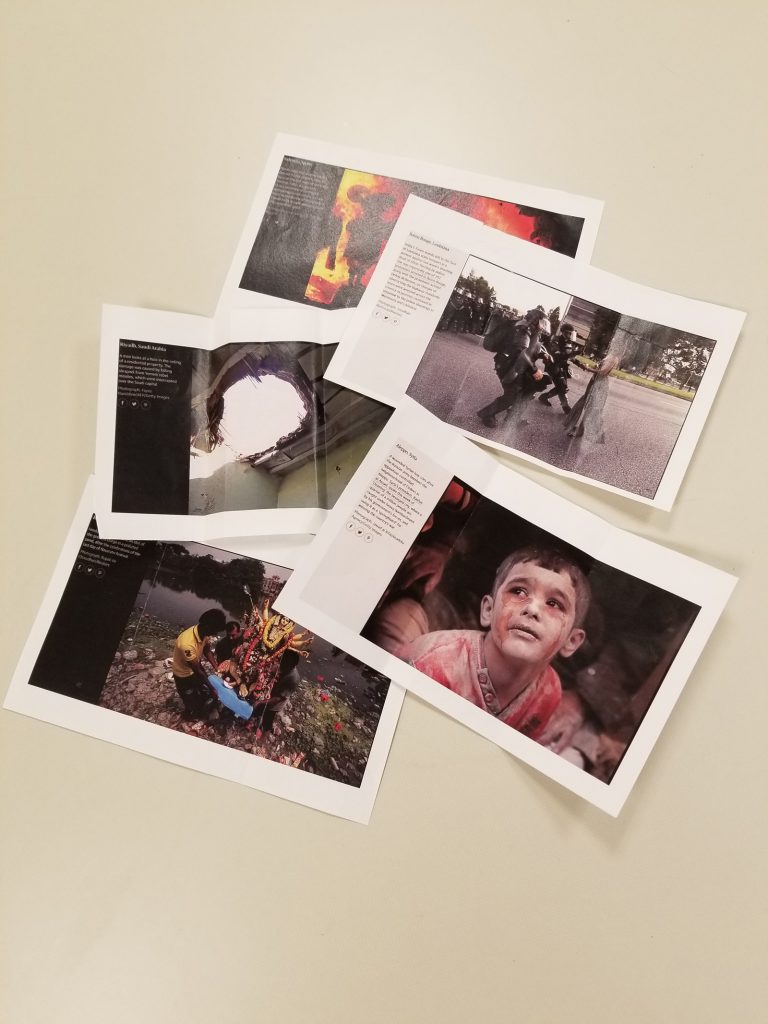

Students open their envelopes to find a photograph of a distressing news event: a woman and her two children in Bangladesh shielding themselves under a tarp as monsoon rains flood the area; a toddler crying as he’s lifted onto a rescue boat while a swiftly moving river rises in North Carolina; a landscape in the Bahamas littered with detritus after a deadly and devastating hurricane. Healey asks students to “be with the image, see what comes up for you, and notice where the image is coming from.” This encounter is based on what is known as beholding, a contemplative practice of pausing and thinking deeply about what is in front of you. It is a practice that is meant to change how we see. Without the distraction of their devices, digital natives—people who grew up with technology and the Internet at their fingertips—are given a chance to fully internalize a snapshot of a harrowing moment in time.

Emily Bourne, a senior communications major, had an image of a young boy escaping a flood in an inner tube. “All I could think of was that I am so privileged,” she said. “I’m here walking through the woods and this little boy is struggling for his life. I walked by a river in the woods and this was all I could think about.” Bourne saw it as a unique way to encounter what she might normally dismiss with a flick of a finger on her phone. “Often times I’ll get a news update from CNN or something, but then it’s gone and I never think about it again.”

Healey said he doesn’t want students to reject technology outright, but to be more intentional in how they use it: “I want them to slow down enough to see who or what is in the photograph and then ask themselves, ‘How does it make me feel?’”

Contemplative studies is an emerging field that combines empirical social-science research—including neuroscience, medicine, psychology, and psychiatry—with first-person contemplative practices like meditation, yoga, the arts, and music therapy. Contemplative practices are meant to not only enhance an individual’s well-being, but also bring about a greater public good.

Healey is one of only a handful of academics in the discipline of media studies who incorporates contemplative practices into their coursework. His unusual approach to pedagogy grew out of his students’ interest in yoga and meditation and a wider growing concern around young people’s tech habits. “It’s funny because they are hyper aware of their inability to connect with other people face-to-face,” he said. “They don’t like to do it.”

Karolyn Kinane is associate director at the Contemplative Sciences Center at the University of Virginia and a colleague of Healey’s who is familiar with his work. “The kind of practices he creates are embodied, contextual, and relational,” she said. “While it seems intuitive, it’s rooted in the best studies in educational theory of what makes for powerful and transformational educational experiences.” The exercise of taking a mindful walk in the woods disrupts the classroom setting. This environmental shift shakes the students out of their routines and primes them to stay open to the harrowing news story, and the absence of technological distractions encourages them to engage with it more fully. The tactile nature of this experience helps make the lesson even more impactful and easier to retain. “Then encouraging a particular kind of presence with an image adds another layer,” Kinane said.

Today’s college students comprise a generation whose attention is now a commodity. “They are growing up in circumstances where . . . government and commercial forces are competing for that attention,” Kinane explained. Contemplative practices to become more aware of habitual patterns around technology seem like a natural fit, and in an overly distracted world, they are long overdue. “It’s pressing to have vocabulary, skills, and space for working with awareness and attention and being aware of the pressures on our awareness,” she said.

Back in the woods, students also find in their envelopes words describing virtuous ideals: justice, forgiveness, bravery, persistence. Using the news images and words as inspiration, they photograph places in their surroundings that connect the disparate scenes and then discuss what they find on the student blog. One student took photos of a weathered, wooden footpath that reminded her of a path to forgiveness filled with twists and turns, bumpy and easy terrain with glimmers of light along the way. Another found a red, heart-shaped mushroom amid the darkened leaves and branches on the forest floor. To him it was about love, but also something more. “It symbolized how to see the positives in dark moments. Everything will be OK. We all just need to love and believe.”

Healey’s contemplative media studies course will be offered again in the fall of 2020, but what remains unclear is how the coursework affects student’s behavior in the long term. Student Emily Bourne said that being a mindful consumer of digital media is a work in progress. “I’m still not seeing these things on my phone and feeling them as much as I want to,” she said. What Bourne has realized, though, is why her generation needs these contemplative practices. “If you aren’t setting aside time to think deeply about what you want to do, you’ll never know. It can help you feel fulfilled in a different way.”

♦

The reporting for this article was supported by Public Theologies of Technology and Presence, a journalism and research initiative based at the Institute of Buddhist Studies and funded by the Henry Luce Foundation.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.