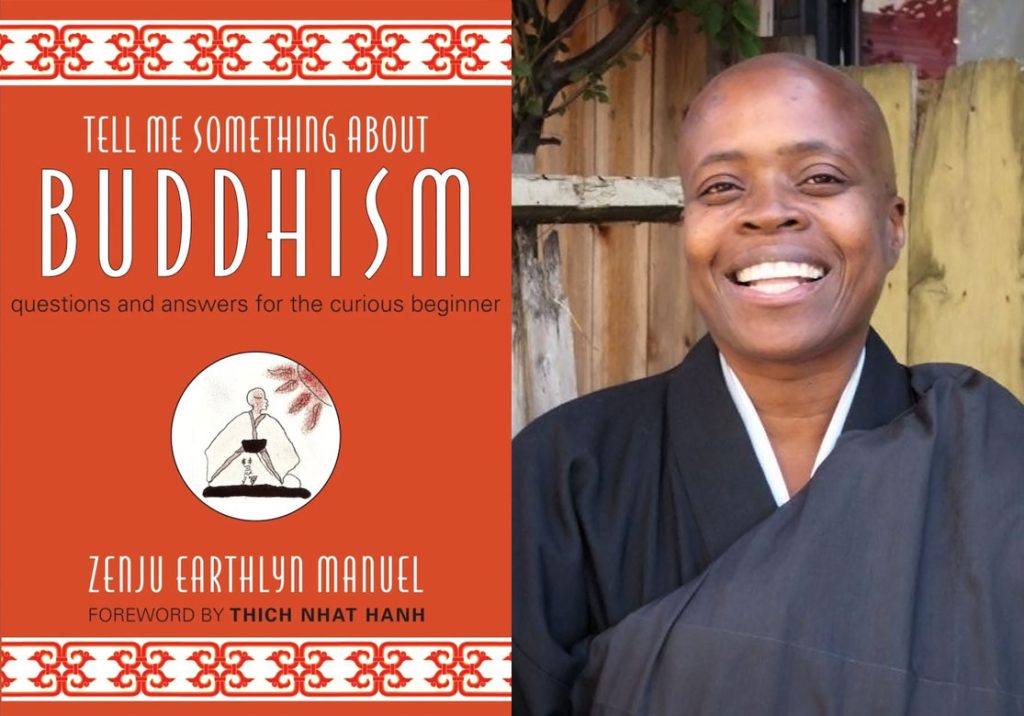

Rev. Zenju Earthlyn Manuel’s new book, Tell Me Something About Buddhism: Questions and Answers for the Curious Beginner, is a simple yet uncommon introduction to the Buddha’s teachings. Manuel, an African-American Zen priest, takes a direct and personal approach to the dharma. “What does Buddhism have to do with black people?” she recalls her younger sister once asking her. In Tell Me Something About Buddhism, Manuel reflects on the ways in which being black has informed and enriched her understanding of Buddhism. “The practice is to make companions of difference and harmony, see them both as oneness itself,” she writes. “We cannot take the teaching of harmony to serve the desire for sameness and comfort.”

After reading Tell Me Something About Buddhism, I wanted Manuel to tell me a little more about her life and practice. Read on for excerpts from our recent email exchange.

How did you come to Buddhism? I was introduced to Nichiren (Soka Gakkai International) when I was eleven years old at a shopping strip in Los Angeles. I remember being fascinated as I was dragged away by my Christian mother. Later the Soka Gakkai practice was introduced to me several times by friends throughout my young adulthood. However, at the time there was an inner pull from Christianity toward the African Yoruba spiritual tradition with a transplanted tribe from Dahomey (in modern Benin.) The tribe returned to Africa, begging me to join them, but I stayed knowing the call to that tradition was bound to resurface—but that is another story. Soon after moving to San Francisco, I was invited to dinner with two friends who had been practicing Buddhism but we first had to go to their Soka Gakkai meeting. After that meeting I began reading Buddha’s teachings and realized just how hungry I was. Finally, I heard what I had felt in my bones all my life—that everyone and everything is interrelated. I knew this but couldn’t understand why others didn’t, given my experience with discrimination and hatred in the U.S. I remained with Soka Gakkai for 15 years, learning how to face the wounds that had piled up at my feet throughout my life.

Why the move from Nichiren to Soto Zen? First I would like to say that the many teachings that have come to me, I carry to the next teaching. So, inside myself Nichiren still is in my cells. I did not move away from it. I still find myself chanting the the title of the Lotus Sutra (as a mantra) when I am in a tight negative situation. Which leads me to the reason I might have taken another path of Dharma. I found the Nichiren tradition as an excellent practice of concentration and learning how to participate wholeheartedly in Sangha. I also learned how to be a teacher in Nichiren as it is important in that tradition to raise leaders starting from the young ones to the old ones. However, I needed a different understanding about suffering so that I would not have to constantly chant but that I would begin to transform the suffering. I believe that can happen in Nichiren but I could not find my way to such change.

One day while doing silent walking meditation in a Zen Center, I realized that I had changed paths. It was seamless. It was time for me to be silent. I had learned how to deal with those tight negative external situations in Nichiren and needed to learn more about my own mind and heart. Even though I was a teacher in Soka Gakkai, I felt called to priesthood and that path was not available to me there. I also felt called to be a minister but the Church of Christ did not allow women to preach. With deeper and deeper spiritual aspiration, I went back to my Nichiren community and announced that I would be following another path. I would have liked to stay with my Dharma family there, but I felt there wasn’t any room for me to combine the two.

Leaving my first Buddhist home was difficult. I had no idea about Zen and knew no one who had practiced it. That was probably a good thing because I began as a baby in a new world, discovering new ways of walking Buddha’s path. I tend to do best in new situations when I have not figured it all out. Eventually, I was able to take the interpretations of Buddha’s teachings by Nichiren and combine them with that of Eihei Dogen’s (Zen) interpretations of the teachings. Therefore, I have a unique way of seeing how the Buddha’s path of liberation affects life from both a chanting and devotional place and from a meditative absorption of life.

How has being a black woman informed your understanding of Buddhist teachings? Buddhist practice is a lived experience for everyone. However, living in a dark female body in this country means the life material for understanding the teachings is constantly in my face. The insurmountable oppression, discrimination, and hatred directed at dark people comprise a thick workbook for Buddha’s teachings. When I walk out my door, it is guaranteed that someone or something will let me know that my dark skin is not good enough or let me know that I am not welcome. All I have to do is look at a billboard, be followed around in the store, or have the clerk smile to everyone but me. So, every moment the depth of my practice as a black woman in the Dharma is one that requires deep-sea diving and unbroken awareness. My understanding of the Dharma comes in living color, so to speak. As a black woman I can see and experience things others may not, which in turn gives me a 24/7 practice of compassion. I have no time to waste, protest, yell back, or play games. And it is exhausting to act out when I feel wronged. So, with Buddha’s teachings I understood that I could change my response to the human condition. I ask each day, how do I walk as vulnerable and as soft as I feel without looking over my shoulder? I walk with what I know to be true if I am awakened to the true nature of my own life. This is my face. I walk with it. That is how I understand the teachings from the body in which I was born.

You’ve said that practicing Buddhism has felt like separating yourself from your Christian upbringing and from other black people. Why was it worth it? How do your friends and family feel about it now? First let me clarify that no one from my family, friends, or those from the church I was raised in blatantly turned away from me because of my taking on a different religious practice. Most of what I felt was an internal process of transformation. I had a grip on what I knew religious life to be in the Church of Christ and I was moving away from it. Church was the place folks who migrated from the Southern region of the U.S. came to find their relatives, their home, their tribe. I was part of that tribe. It was a place I was born, grew up being loved by this one and that. So, leaving the people, the collective prayer, the songs, the communion, the knowing of Christ’s teachings as the way we survived as black people, was difficult. I was leaving home, following a call for something that spoke of freedom in the truest sense—not just freedom from poverty and injustice, but freedom within my heart.

In the end, I did not leave black people. I found us along many different paths once I came down those church steps into the world. We were everywhere. And yes, even when I stepped onto Buddha’s path there were many black people. However, in Zen the numbers were small or non-existent. And this is where I questioned my being a part of a mostly white Sangha. Why was it worth it? I can say that I have walked the hot coals of oppression in the white Sangha and survived. I can teach others how to survive by my being in the pit of our ignorance of each other. At the same time, I was astonished by the love I received in this Sangha that was entirely different than my black church. Even the people of color had different values than the ones I was raised with. So, culture clash was happening all around me. And in this clash I learned. I was no longer ignorant of my interrelationship with everyone, even if there was pain in our being together. I learned that I did not know how to love because my energy was taken up with who and what I hated. Yes, it was worth it to gain a few giant steps toward complete liberation. And I hope to wear my robes one day into my home church and do what I had dreamed of as a child—preach in the pulpit.

Tell me about the tension between “feeling African and being buddha.” How can Buddhist communities best honor multiculturalism and express the universality of the Buddha’s teachings? When I was taught Buddha’s Two Truths, I heard the choir sing hallelujah. There are two basic truths in regards to the nature of life—the relative and the absolute. These teachings are vast, but briefly, the relative is that which you can sense about life—what you see, taste, smell, etc. While the absolute nature of life goes beyond those senses, seeing into the true nature that we cannot touch or see. So, the tension between the two is inherent in our existence. We can find ourselves holding to the relative and not the absolute or visa versa. When I can be African or descended from Africans and be awakened to life, be buddha within my darkness, the tension dissolves. With Buddha’s teachings of the Two Truths, I returned to that expansive way of seeing myself before I was told that I could not go to a particular place because I was black. I returned to that original moment when I was born free from the hatred placed on darkness and on dark things and dark people.

As far as Buddhist communities honoring multiculturalism, I wonder how many white Buddhists are asked this question. When white Buddhists are asked this question as much as those of color, then we began to see the wheel of Dharma turning in a forward motion. We often want to look back and see what we haven’t done rather than look forward and change what we are doing. I feel it is crucial to support other kinds of Buddhist communities that will be created by folks from different cultures. Instead of re-shaping what has already been done, allow for something new to be constructed and not worry about whether it is too far from the root or not. We have already gone a long ways from Buddha’s days. If new relations look and sound different, existing western Buddhist communities must be willing to open to that difference rather than saying, “This is how we do it.” If not, what is different will disappear and what is left is the same. And perhaps keeping a particular sameness is the intention. If so, then that must be acknowledged and the quest for diversity set aside. I say this knowing there are many who will not want to or not able to honestly assimilate into the current western Buddhist communities and therefore the practice must take shape again and again for the people, the time, and the place.

Why do you like to think of the Buddha’s enlightenment as a “vision quest”? I like to think of Buddha’s enlightenment journey as a vision quest because it connects his teachings to the earth. It brings Buddhism back to its origins as an indigenous earth-based wisdom tradition. In the re-shaping of the path for U.S. culture, I feel there are many who like to distinguish Buddhism from pagan practices, from Shamanism, or spirit work. Yet, all that Buddha did on his journey was done in the forest, not in a Buddhist center. He sat in the dark, upon the roots of various trees, and listened to his heart, seeking answers from nature. This is exactly what one does on a vision quest, which is a practice in many indigenous spiritual practices.

Personally, holding Buddha’s enlightenment journey in this way allows me to integrate a sense of spirit as part of the path. It allows me to include what has been suppressed or taken out of many westernized Buddhist practices in this country. Recently, I watched a film called The Oracle by David Cherniack, where the Dalai Lama consults with other worldly spirits. It is an important “coming out” so to speak for the Tibetan tradition and Buddhism as well. In the title of the film Cherniack refers to the Oracle as a 400-year-old secret; but it is not a secret to those who have always held the sense of spirit pervading all. Buddha taught that everyone and everything is interrelated. We cannot leave out anything or make one kind of spiritual consciousness superior and the other inferior. I am so sensitized to that teaching, again, because of how I am embodied.

Finally, African spiritual traditions have existed 8,000 to 10,000 years and I do feel that because of such longevity other spiritualities, religions, or philosophies have been influenced by ancient traditions. Buddhism is not exempt.

What is the purpose of the Sangha on the Buddhist path? In Sangha, everyone has come together with an expressed willingness to deal with their suffering and its impact on others. There is an expectation that all will be good in the land of meditation. We expect the ground beneath Sangha to be stable and strong when, in truth, we are together in the confusion and challenge of living awake. One day, things are one way, and the next a relationship has changed. You feel you’ve made a mistake, and you begin to blame your discomfort on the forms, the Sangha members, or the teachers. Even though all experiences are valid, they still need investigation. This investigation can be carried out in the midst of the troubled souls, the Sangha, you have chosen to commune with. You could leave and find another community, but what happens for you when the earth begins to shake beneath the new Sangha in the same way as it did underneath the Sangha you left?

Many who take on the practice decide to practice alone. Perhaps their workplace, family, or other communities serve as Sangha. However, the difficulty with such Sangha is that the path of awakening can be unclear, or there may be no conscientious effort on the part of others to walk a path of awakening with you. You may not have the support you need to follow the teachings you have embraced.

In Sangha based on the teachings, you are reminded that you are not alone on the journey. At the same time, I have felt alone in Sangha. I have felt different than the others, and many times this difference stood out in a way that was uncomfortable. Then it was time for me to remember that everyone’s path is different. There is no one with exactly the same path as my own. So how do I respond to the uncomfortable situations?

Our Sangha friends are there to assist us by reflecting back to us the ways in which we respond to the events of life. This reflection doesn’t mean that these friends are to sit in judgment of our actions or inform us of any wrongdoings. The reflection is silent. It is in the way we see ourselves in each other. When a friend falters or experiences discomfort, we, in turn, are there to witness the faltering and the discomfort, sensing the familiarity of their situation in our own life. When a Sangha member is happy, we see the joy in our own lives.

Many have said to me that they do not need Sangha. My response has been, “Then where will you go when you begin to experience liberation? Who will know the journey you have taken and your vow to be awake?”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.