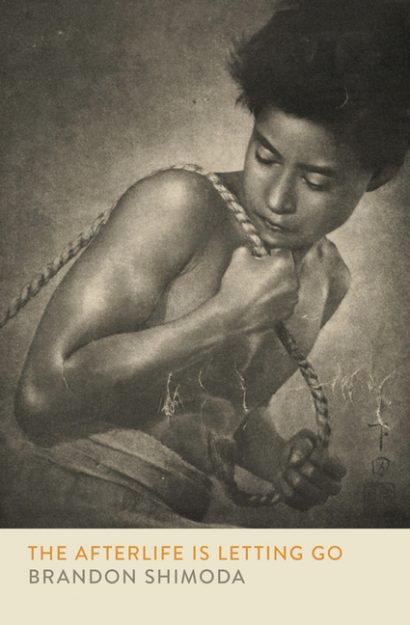

The following excerpt is from The Afterlife Is Letting Go, an essay collection by Brandon Shimoda that examines the ongoing legacies of the US government’s mass incarceration of Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans during WWII. Drawing from years of archival research, visits to the ruins of incarceration sites, interviews with survivors and their descendants, and the author’s own family history, the book explores themes of history and memory, mourning and memorialization, ancestors and ghosts, and the resonances between forms of oppression and state violence across time and space.

***

After their first winter in prison, and after the snow melted, the Issei at Fort Missoula noticed, all over the prison grounds, stones. Stones of infinite color, shape and design. “Perhaps this is the site of an ancient river or sea,” wrote Iwao Matsushita, one of the prisoners, in a letter to his wife, Hanaye, “for polished pebbles are strewn all over and everyone is immersed in collecting these stones,” adding: “like children” (March 9, 1942).

Hanaye received Iwao’s letter at home in Seattle. She would soon be removed to Puyallup, then Minidoka. Iwao was detained by the FBI in the hours after Pearl Harbor. He arrived in Missoula on December 28, 1941. The valley that Sunday was covered in snow. In the spring, the ground softened, stones grew like flowers. The men gathered and polished the stones, made jewelry, sculptures, gifts for their families. Iwao mailed stones to Hanaye. “So avid is this stone picking,” he wrote, “that it is said that anyone not involved in this hobby is not human.”

Gathering stones was a way to be, in the midst of being criminalized by the country to which they had committed their futures, “human, like children.” But children did not need to be a likeness, the innocence of the men, or the emphasis of their condition. They were there too—in the camps, stone-picking their own prison grounds. “We were children, hunting stones,” writes David Mura, in his poem “An Argument: On 1942.”

I moved to Missoula in August 2004 to begin my first semester in the MFA program in Creative Writing at the University of Montana. The commitment to be, or becoming, a poet was less about enrolling in a graduate program, and more about being close to my grandfather.

I felt his presence, especially at night. Some nights I heard his voice. Distant, the amplitude of an ember. I wanted to bring his presence and his voice to where I was, or bring myself down to where I felt him to be: buried—beneath the accumulation of withholdings and refusals by which the truth of his experience was obscured. By buried I mean also arrested: that some part of him had not managed, or been permitted, to be released, to join the rest of himself in the future.

I spent four years wandering Fort Missoula. I did not know what I was looking for. I felt like the woman in Brynn Saito’s poem, “Stone Returns, 70 Years Later,” who, visiting Manzanar, “paces the length / of the barrack blocks, // the dead weight of midnight like a sea.” She drops a stone into her pocket, “slips into the night to stand in the field // and summon ghosts.” The woman caresses the stone like a rosary. What, if and when the ghosts come, will happen? What will she—what will I—do? Stop pacing? Go home?

I brought with me Imprisoned Apart: The World War II Correspondence of an Issei Couple, a collection of Iwao and Hanaye Matsushita’s letters. My grandparents, who met shortly before my grandfather was sent to Fort Missoula, did not write letters to each other, none my grandmother saved or could remember. Iwao and Hanaye’s letters became surrogates, idealizations. They wrote beauty and sadness, about when they would see each other again. I was drawn especially to their inventories of the weather, wildlife and wildflowers:

“Frozen fog makes branches beautiful with snow flowers against the azure sky. . . . Spring is deep, but the weather is unsettled. . . . Garden flowers are blooming one by one, but we have seldom chance to see them. . . . I’ve enjoyed the dry pressed flowers enclosed in the last letter and cried with nostalgia remembering the fun days we’ve had. . . . Listening to the quiet rush of the river in the morning, I feel as though you are calling to me. Even the coyote’s howl is nostalgic. . . . I haven’t heard any coyotes recently, though once in a while I see a scorpion. . . . The spring flowers don’t move me as much since I saw them all last year. . . . Almost a year has wasted away since we parted. . . . I plan on turning to ashes.”

I read the letters in the barracks, the long fields, the road, by the river. I had a hard time believing the barracks, so undemonstrative, with their charming, willowy air, corresponded to my grandfather’s prison. Iwao’s letters were written not far from my grandfather. If I could hear Iwao’s pen moving across the paper, then I might be able to hear the sounds that surrounded his pen, his breathing, the sounds in the room, that surrounded the room, out the door, my grandfather somewhere on the edge of those sounds.

I was not introduced to the work of a single Japanese American poet in graduate school. Nor, for that matter, in any classroom between preschool and Missoula, Montana. There were no Japanese American poets on any syllabus or reading list, none were mentioned in class. It could have been construed from their absence that they were not relevant to the study of poetry. The tradition by which I was meant to understand myself was predominantly white, European American. If I was going to have a relationship with non-white poetry, especially by Asian Americans, especially by Japanese Americans, those relationships would have to be fugitive—trysts.

The Mansfield Library was named after Senator Mike Mansfield. Statues of him and his wife, Maureen, stand in a small grove of trees in front of the library, Mansfield gazing into campus with cryptic determination, Maureen gazing worshipfully, yet apprehensively, at him. Mansfield served on the board that interrogated the Issei at Fort Missoula. I could not go to the library without being forced to feel that same gaze pressing into my grandfather, and the gazes of all the hoary white men who believed, as Mansfield did, in their ability and authority to assess the fitness of a Japanese man to be free.

Poetry was in the basement. I never saw anyone. I was always alone. I discovered, down there, in that solitude, my first Japanese American poets: Mitsuye Yamada, Lawson Fusao Inada, Janice Mirikitani, all of whom were incarcerated—Yamada as a teenager in Minidoka, Inada as a young child in Jerome and Amache, Mirikitani as an infant in Rohwer. Their names glowed on the spines. Time froze, flowed backwards. I sat on the floor, and floated into the attention of these uncanny poets, their voices close, more precise.

In the introduction to Legends from Camp, Inada, sitting in a petrified forest on a summer night, shares a “simple show-and-tell” about Japanese American history, using stones scattered around the forest as reference points. “For starters,” he writes, “let’s say these rocks over here are Japan. And this smooth one where we’re standing—with the sand on it, see?—is Amache, in the Colorado desert, not all that far from here. While we’re at it, let’s let that little stone by your foot stand in for Leupp—a ‘mini-camp’ right here on the Navajo Nation. (And, yes, we had major camps on other reservations; so you might say that it makes sense that the chief camps administrator went on to become chief of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, where he ‘re-deployed’ his policy of ‘relocation.’ Which included, yes, ‘termination.’ Which reminds me—down the ridge, in Europe, our relatives had base camps in Italy, France, Germany, and some of them liberated a camp called Dachau.)”

In Mitsuye Yamada’s “Search and Rescue,” an old man, thought to be “out of his head,” wanders beyond the barbed wire fence and disappears. A search party goes out. Yamada describes the “feel of freedom” of following the man’s “twisted trail” through “gnarled knuckles” of greasewood. Where did he go? Maybe he was not “out of his head”—maybe he was not even old—but in his right mind, leaving behind him a “twisted trail” to throw the search off. Maybe he was trying to get free.

In “Shadow in Stone,” Mirikitani visits Hiroshima (August 1984), wanders along the Motoyasu, the tributary of the Ota nearest to where the atomic bomb detonated. “The river speaks,” she writes, then the river speaks. “I received the bodies / leaping into my wet arms,” the river says. People, on fire and melting, jumped or fell into the water and died, many of them immediately, against each other. “I seek solace in the stone,” Mirikitani continues, “with human shadow burned into its face.” The bomb emitted a flash so bright, it imprinted people’s shadows onto the ground. A man sitting on the steps of a bank, for example, waiting for the bank to open, his memory made permanent on the steps. “I want to put my mouth to it,” Mirikitani writes. I was shocked by the nakedness of her desire to kiss or breathe life into a shadow, but what was more shocking? “The Americans / have licked the core / of your inner organ!” wrote Seishu Hozumi, tanka poet, hibakusha.

I visited Hiroshima for the first time when I was 10. My sister (13) and I walked along the Motoyasu, the reflection of the skeletal Genbaku Dome wavering in the black-green water. I do not remember my parents. They were there, they brought us, it was their idea, where were they? The question seemed to be: What does it mean to be American? Or, what does America mean? Or, what does America do? Or, what does it mean to be you?

“The atomic bomb was part of incarceration,” Emiko Omori said. She and her sister Chizu, both of whom were incarcerated in Poston, were visiting my class—Literature of Japanese American Incarceration, Colorado College (2023). We watched their documentary, Rabbit in the Moon, the day before. We talked about the processes of dehumanization at which the United States excels, and how the dehumanization of the Japanese American community helped shape the national disposition towards the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki into a debate over whether or not the mass murder of over one hundred thousand people in an instant—the spontaneous release of a million suns; the incineration, first thing in the morning, of children on the banks of the Motoyasu—was “justified.”

Rabbit in the Moon begins with Emiko Omori speculating on why she did not have children. Over images of children holding hands in a circle, twirling parasols, playing with a dog, eating noodles in highchairs, Omori says, “Like me, my child would be an American, trapped in the body of an unwanted alien race. Could I conceal from my child how I wished he or she was more white, so as not to suffer the rejection I had just because of my face?”

This question, and these images, are preceded by a story about stones: “In the 1950s a Wyoming farmer unearthed a 55-gallon oil drum on land that was formerly a World War Il concentration camp. It had been buried by the inmates. It was filled with hundreds of small river stones . . . each one carefully inscribed with a Japanese character . . . coming to light like fragments of memory.”

The story is also told in the final pages of both Karen Ishizuka’s Lost and Found: Reclaiming the Japanese American Incarceration and Duncan Ryuken Williams’s American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War. The Bureau of Reclamation, operating a road grader near the cemetery, hit the oil drum. There were almost two thousand stones. They were given to the white couple who owned the land (Nora and Les Bovee), who gave them as gifts to people who visited Heart Mountain. “They were my guiding light,” Emiko Omori told me, about the stones. “Whenever I wavered or wanted to throw in the towel when working on Rabbit, the little stones kept me going.”

According to American Sutra, two Japanese scholars determined that the characters on the stones were written by Nichikan Murakita, a Buddhist priest and master calligrapher, who was incarcerated with his wife, Masako, in Heart Mountain. They determined that Murakita had written one character per stone, the Scripture of the Blossom of the Fine Dharma, the Lotus Sutra.

In “Picking Up Stones,” Lawson Inada tells the story of another Buddhist priest, Nyogen Senzaki, also incarcerated in Heart Mountain, who:

went about gathering pebbles

and writing words on them—

common words, in Japanese

with a brush dipped in ink.

Then he’d return them

to their source, as best he could

Other incarcerees made a game out of gathering Senzaki’s stones, but:

it was difficult to tell

which was which:

“his” pebbles, just plain pebbles,

or those of which, in his hands,

had remained mute, dictating silence . . .

In her poem “The Well,” Amy Uyematsu suggests that the stones were not the work of a single individual, but were

each inscribed

by a different hand,

each crying out.

And that each stone was inscribed with something different: the name of a person, a family, a single kanji

snow wind cold sky

shame home bird.

The Bovees donated the rest of the stones to the Japanese American National Museum. A man named Shinjiro Kanazawa wrote a letter to the museum saying that the stones were written by the parents of deceased children and should be treated accordingly. “When a child died,” Ishizuka writes, paraphrasing Kanazawa, “grieving parents would write passages from sutras—and sometimes their children’s names—on pebbles and build the stones into piles in order to help the deceased safely enter the other world.”

There is a place children go when they die that is filled with stones of infinite color, shape and design. Sai no Kawara, the Dry Bed of the River of Souls. When the children find themselves—abandoned, bewildered—in the Dry Bed of the River of Souls, they begin, instinctively, to gather stones which they build, instinctively, into towers. It is only after building towers of stones that the children are able to achieve their afterlife. That is the instinct: The afterlife is inborn. But the children are not alone. With them in the Dry Bed of the River of Souls are demons who knock over the towers, scatter the stones. The demons appear, in 16th-century scrolls, red-hot and naked, with horns, fangs, and hooves, wielding iron clubs, wild manes whipping back, eyes pulling at their nerves, but that is not, or not exactly, how the demons appeared in the 20th century, and that is not how they are appearing in the 21st. The children, however—and however terrorized they are—are undeterred, and keep gathering stones, keep building towers, keep striving, together and alone, to cross the threshold out of the underworld and into the afterlife.

“To live in Zen,” said Senzaki, in his final dharma lecture (June 16, 1957), “you must watch your steps minute after minute, closely. As I have always told you, you should be mindful of your feet.”

I was invited by Williams to write a response to Senzaki’s poetry for a book he was editing on the subject of religion in camp: Sutra and Bible: Faith and the Japanese American World War Il Incarceration, a companion to an exhibition of the same name at JANM. I did not know that Senzaki wrote poems, but of course he did. The act of “gathering pebbles” and writing “common words” on them, then returning them to their “source,” is one definition, maybe one of the clearest, of poetry. Here is the poem that I wrote:

The Empty Hands

for/after Nyogen Senzaki

I cannot help

but see

and yet struggle to see

in Nyogen Senzaki’s poems

faces

floating

along the body

of a snake

black, winding away

from the spring flower

blooming in

America,

that is

the ritual effacement

of those whose faces

I cannot help

but see

in ours, in yours

in my own

floating along the body

of a silent, surreptitious snake

like scales, like sequins, shining

suns

like suns

shining into

the future

with the shades drawn

That is where we, the descendants, are

and where we will always be

Beckoning them

with the empty hands

of those from whom everything was taken

Faces

separated

from their bodies

bodies arrested, separated

into phases

that constitute what passes

for history

There is no such thing

There is teaching. There is learning

There is heaven, earth

but history? There is no such thing

if the light of a face

if the light of many thousands of faces

takes generations to reach us

and to be seen

clearly

and to not even be seen, clearly

but as a figurative concentration

there is no such thing

There is teaching, there is learning

that is heaven, that is earth

that is the endless reconstitution of face

into the meaning and the order

of independence

in between

heaven and earth, the empty hands

open, and introduce

their emptiness as sanctuary

but, as the scripture of a harder-won fate

will have it,

cannot be filled, cannot be taken

or even touched

by the lives—by the faces

rising off the winding body

and to which they are held out

to which they are conditioning

their beneficent and beautiful atmosphere

to hold

The empty hands

must remain

empty

or they are not

♦

Brandon Shimoda, excerpt from “Dry Bed of the River of Souls” from The Afterlife Is Letting Go. Copyright © 2024 by Brandon Shimoda. Reprinted with the permission of The Permissions Company, LLC on behalf of City Lights Books, citylights.com.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.