Zig Zag Zen: Buddhism and Psychedelics (2nd edition)

Edited by Allan Badiner

Synergetic Press; May 2015

304 pp.; $38.95 (Cloth)

It was something I noticed back in the early 1980s, when I was working as a newspaper reporter and interviewing longtime members of San Francisco Zen Center. I’d ask them how they got interested in Buddhism, and I’d keep hearing about “the long, strange trip.”

“Well,” the answer would go, “I guess you could say it started with that first acid trip back in 1965.”

This fall marks the 50th anniversary of the first San Francisco “Acid Test,” when a promising young writer named Ken Kesey gathered the infamous band of Merry Pranksters and spiked the Kool-Aid. It was 1965, the same year that another early psychedelic explorer, ousted Harvard psychology professor Richard Alpert, headed out to San Francisco, the first stop on his pilgrimage to India, where he’d be reincarnated as Baba Ram Dass.

Today, psychedelics (and Kesey’s house band, the Grateful Dead) are very much back in the news, and so is the debate about how and whether getting high on psychoactive substances should be part of the Buddhist path.

First, the news: The final stage of government-approved clinical trials into the medical use of MDMA, also known as “ecstasy,” and psilocybin, the active ingredient in “magic mushrooms,” is expected to begin next year. Promising early results show that MDMA-fueled psychotherapy sessions can help people suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, including thousands of troubled American soldiers returning from wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Other research indicates that supervised sessions with psilocybin can greatly help cancer patients deal with the “psycho-spiritual distress” that often accompanies a life-threatening diagnosis. As early as 2020, researchers now predict, MDMA and psilocybin could be reclassified by the US Food and Drug Administration and routinely used under the watchful eye of trained therapists.

Meanwhile, legal restrictions are also loosening for some religious groups that use psychedelic plants in their rites and ceremonies. Following earlier court rulings allowing Native Americans to legally use peyote in their spiritual practices, a 2006 Supreme Court decision granted similar protections to North American congregations affiliated with two Brazilian churches that use ayahuasca, a psychedelic tea, in their ceremonial life.

Ayahuasca devotees outside those Brazilian sects are also starting to come out of the shamanic closet. All-night sessions are not hard to find among Brooklyn hipsters and Hollywood trendsetters. Mainstream media coverage of the new wave of psychedelic research and rituals has been overwhelmingly positive and restrained—unlike a wave of sensationalist coverage in the late 1960s that conspired to allow Congress to pass the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, which helped shut down 20 years of early research into the beneficial use of psychedelics.

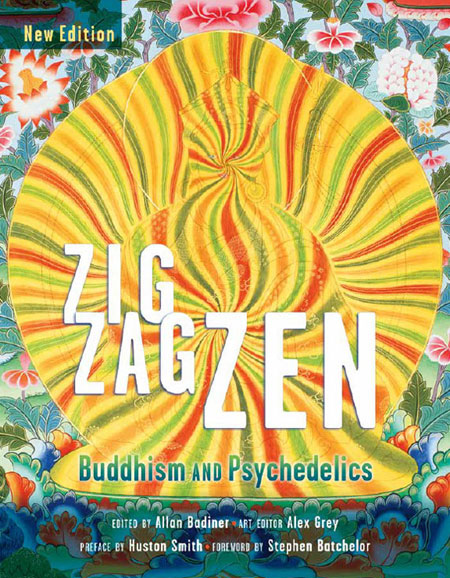

This shifting psychedelic landscape makes the new edition of Zig Zag Zen: Buddhism and Psychedelics, edited by Allan Badiner and published by Synergetic Press, all the more timely. Like the first edition, published in 2002 by Chronicle Books, this hardcover volume is vividly illustrated with visionary art, including a new foldout centerpiece featuring the work of Android Jones.

Most of the essays are reprints from the first edition, but two of the new offerings point to some of the changes over the past 20 years. The first is an interview with Rick Doblin, the founder of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, or MAPS. He has raised close to $20 million to support drug researchers and persuade federal regulators that MDMA can be safely and effectively used to ease the psychic pain of war veterans and sexual abuse victims. Doblin, who had his first LSD trip as a college freshman in 1972, talks in the interview about the Zendo Project, which offers psychedelic harm reduction services at the annual Burning Man festival in the Nevada dessert.

The psychotherapist Ralph Metzner pens another one of this edition’s original essays: “A New Look at the Psychedelic Tibetan Book of the Dead.” He is the author (along with Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert) of the influential 1964 book The Psychedelic Experience, a manual on how to take an LSD trip. Metzner, Leary, and Alpert based their tripping manual on the Tibetan Book of the Dead, a self-styled English translation of texts popularized by the American Theosophist W.Y. Evans-Wentz, first published in 1927. Whether or not The Tibetan Book of the Dead reflects ideas that are authentically Tibetan or Buddhist, Metzner and his coauthors helped establish the idea that a psychedelic drug trip was another route to the mystical insights one could achieve—with much more work—through the discipline of Buddhist meditation.

“Psychedelic travelers could be guided, or guide themselves, to release their ego-attachments and illusory self-images, the way a Tibetan Buddhist lama would guide a person who was actually dying to relinquish their attachments,” writes Metzner.

Fifty years later, the psychotherapist is more convinced than ever that “the two most beneficent potential areas of application of psychedelic technologies are in the treatment of addictions and in the psycho-spiritual preparation for the final transition.”

Buddhists teachers who were interviewed or wrote their own essays in Zig Zag Zen disagree as to what extent psychoactive drugs can help or hinder those on the Buddhist path. Some say they offer a glimpse of another way of being and can open a door. Others, such as meditation teacher Michele McDonald, just say “no” to psychedelics. “Drugs promote attachment to experience,” she writes. “What you actually get from drug experience is the desire to take the drugs again.”

Psychedelic drugs can produce feelings similar to those reported by religious mystics—a sense of oneness with the universe, transcendence of time and space, an intuitive knowing, a deeply felt positive mood, and a sense of ineffability and paradox.

Huston Smith, the noted religion scholar who writes the preface, once told me that it doesn’t matter much if a religious experience is “real” or drug induced. It doesn’t matter if your mind is altered by 250 micrograms of LSD or years of long meditation retreats. What matters is what you do with the experience. Do altered states lead to altered traits?

This all sounds a lot like the debate that the editors at Tricycle inspired nearly 20 years ago when the magazine devoted an issue to the subject of Buddhism and psychedelics.

Their conclusion then seems like good advice today: “Just Say Maybe.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.