Forget about enlightenment for a moment. Let’s talk about how different the world would be without self-hatred.

I should start by acknowledging that when I went on my first Zen retreat and heard the teacher speaking about self-hate, I truly believed that I didn’t have any. How was this belief possible? Because I couldn’t admit to something I couldn’t see. Truth be told, I simply had no idea that not only did I have a full share of self-hate but, in many ways, the inner critic was running my life, influencing decisions around every bend.

When I first started to question my inner negative self-talk it freaked me out. It was creepy. “Who is this voice inside my head?!” I found myself asking. It was like I was in a bad sci-fi movie. There were the obvious psychological conclusions: “Oh yes, that’s the voice of my dad. Yep, there’s my internalized mom.” But with just a bit of exploration, I quickly saw that things were more complicated than that.

I saw that I had negative self-talk that had nothing to do with my childhood. I saw that some of the roots of what I told myself couldn’t be traced to anything logical. In fact, I saw that this negative self-talk actually wasn’t “mine.” It didn’t belong to me; I had simply always claimed it.

And here lies one of the greatest gifts of practice—the capacity not to take personally what you’ve always assumed to be yours—in fact, not only what you’ve assumed to be yours but what you’ve assumed to be YOU. Remember, you are not your thoughts or the voice of the inner critic.

This is intensely important personally, and it’s imperative collectively. We can’t disidentify from negative self-talk when we claim it as ourselves. One way I support practitioners in being able to question the voice of their negative self-talk is by externalizing this voice.

How would you respond if a person were following you around in your life, commenting on your every move, most commonly with criticism or, at minimum, veiled judgment that serves to “help, protect, support you in being ‘realistic’”? How long would you keep this “friend” around?

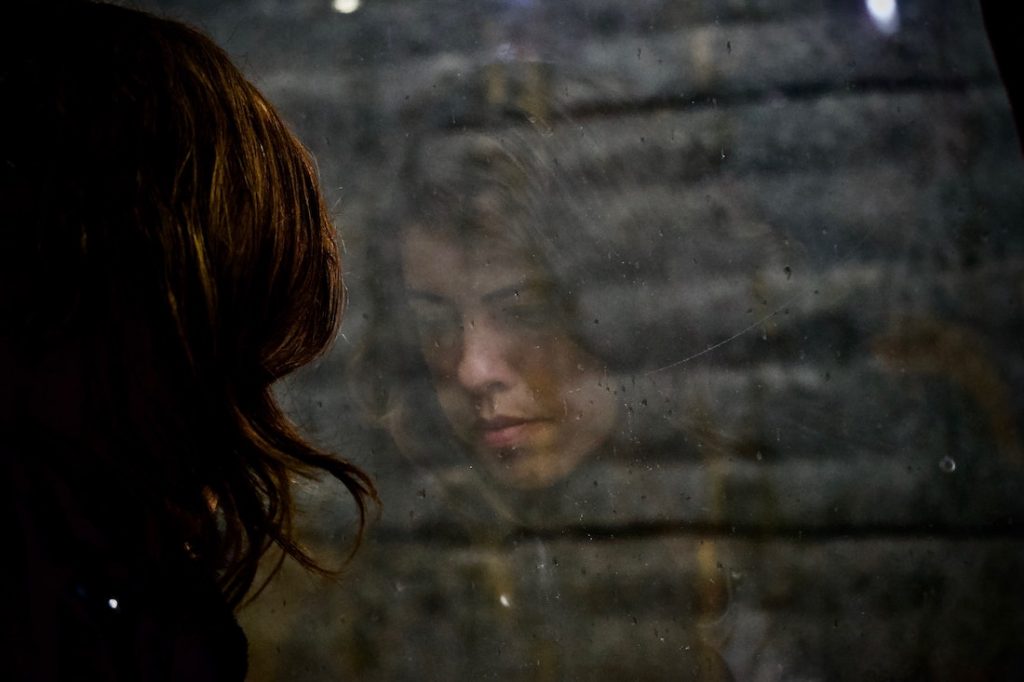

For many of us, the journey from negative self-talk to an experience of full-blown self-hate is short. And self-hate is a glue of sorts—holding the structures of the conditioned mind together. Imagine looking at the world through tinted glasses and continually assuming that it is reality. In meditation practice, the glasses come off. We see the tint as something that belongs to glasses rather than a reflection of truth—rather than an experience of reality. But we must begin by inquiring about what we’ve been looking through.

The reason that self-improvement ultimately doesn’t work is that, in reality, there is no separate self to improve.

If you’re constantly being bombarded by a voice that suggests that you are not enough, that there is something wrong with you, you become so busy defending against this voice, agreeing with this voice, fighting this voice, that often there’s little energy left to inquire into the nature of this voice, and little space to ask who this voice is even referring to.

The ego takes everything personally. It’s a masterfully designed self-referencing system. Everything comes back to “me.” And self-hate keeps it all in place. Remember, the ego isn’t real. It is the activity of the conditioned mind. Think of it like a hologram. There’s nothing solid about it. It can’t actually be found when you look for it.

My first Zen teacher used to say that true spiritual practice can’t begin until self-hate ends. My experience is not so linear. Yes, it can be helpful to name some basic steps of practice, which can be viewed in a linear fashion:

Step 1: See it. Recognize that the voice of the inner critic exists.

Step 2: Name it. Cultivate the capacity to say, “Ah, there’s the voice of the inner critic again.”

Step 3: Let go. Further inquire into the illusory nature of this voice to disidentify, to release the grip.

Step 4: Return. Align with awareness of the voice rather than the voice itself. Return to presence.

However, having taught this process to teens and adults for over twenty years, I have come to recognize that this ongoing practice is shaped like a spiral, not a line. If we cling to the idea that we have to get rid of self-hate before we can get to the “real practice,” then we’re feeding the distortion that there is a self who needs to get rid of something in order to get somewhere else. This keeps in place not only a limited belief in a separate self but also a linear view of time.

It’s difficult to ask ourselves foundational practice questions like “Who am I truly?” if we’re mired in conversations about worthiness. And we must be careful not to give too much validity, attribute too much reality, to a hologram, otherwise our practices can easily slide into “self-improvement.”

Remember: The reason that self-improvement ultimately doesn’t work is that, in reality, there is no separate self to improve.

It’s not my experience that, through practice, negative self-talk—the voice of the inner critic—disappears forever. To believe so gives this illusory voice in our heads a solidity it doesn’t actually have. It is my experience that through practice we become clearer and clearer about what this voice is and therefore we tend to fall for its shenanigans less and less frequently.

This is not to say it never arises again. We can think of the workings of the inner critic as storm clouds. We could say that over time, with practice, we believe less and less that every time the clouds roll through, the sun has disappeared. We can, absolutely, focus on the recognition that not only does the sun not disappear but we are the steady sun, while the clouds do whatever the clouds do. They are transitory. Impermanent. We are undisturbed.

There is plenty of room for any and all weather patterns in the truth of reality. The reality is that we are not the weather patterns. The reality is that the weather patterns arise in us, pass through us, and dissolve in us. There’s plenty of room for storms to do what they will as we inquire: Who am I? Who are we? What is “us”?

It’s liberating to realize that we don’t have to get rid of anything to know who we truly are.

When we are identified with negative self-talk, the ego is legitimized. It gets fed. Where we place our attention matters. What we feed, grows. This feeding process doesn’t make the ego more real but rather more believable. Practice challenges our conditioned beliefs. And in this challenge, what isn’t true dissolves.

Practice: Inquiring into Negative Self-Talk

Create a list. On one side of the page, list the negative self-talk; on the other, the result, the impact.

|

The Negative Self-Talk |

The Impact |

|

I’ll never get this project right |

Missing all my deadlines |

|

I’m such a lousy father |

Missed opportunities to genuinely listen to my daughter |

|

People are not interested in what I have to say |

My voice is not included in group decisions |

Now inquire into the illusory nature of all this. Allow yourself to be a scientist of the self, seeing how it all works. To be clear, just because I’m talking about it as illusory doesn’t mean that it is entirely unreal. There’s a particular reality to the felt sense of isolation, isn’t there? By using the word illusion in this case, I’m referring to how this voice isn’t what it appears to be. It’s not Reality with a capital R. That’s what inquiry opens the way for. Questions like:

- What is this voice?

- What is the impact of believing this voice? Is this voice mine?

- Is what this voice is saying reality? Does it assert the truth?

- Am I this voice?

- Where do I look for the answers to this question? Who am I without this internal conversation?

When we step back from the workings of the inner critic and its cycles of negative self-talk, we see these workings simply as processes of suffering. We have greater clarity about how these processes normalize the absurd.

⧫

Adapted from the book The Heart of Who We Are: Realizing Freedom Together by Caverly Morgan. Copyright © 2022 Caverly Morgan. Reprinted with permission from the author and the publisher, Sounds True.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.