A young man lies on his side, bathing in a sunbeam in a bare Japanese-style room. The window is open, perhaps to let in the fresh breeze on a pleasant day. One bird perches on the sill, then another. In moments, a menagerie of neighborhood fauna surrounds the dozing figure.

Startled, he suddenly awakes.

“N-No, no!” he says. “I’m not passing into nirvana!”

Shooing away the gathered animals, he shouts: “Butt out, buddy!”

Just then, his slender roommate enters the room, cracking a joke at the napper’s expense.

“Did you say ‘Buddha buddy’?”

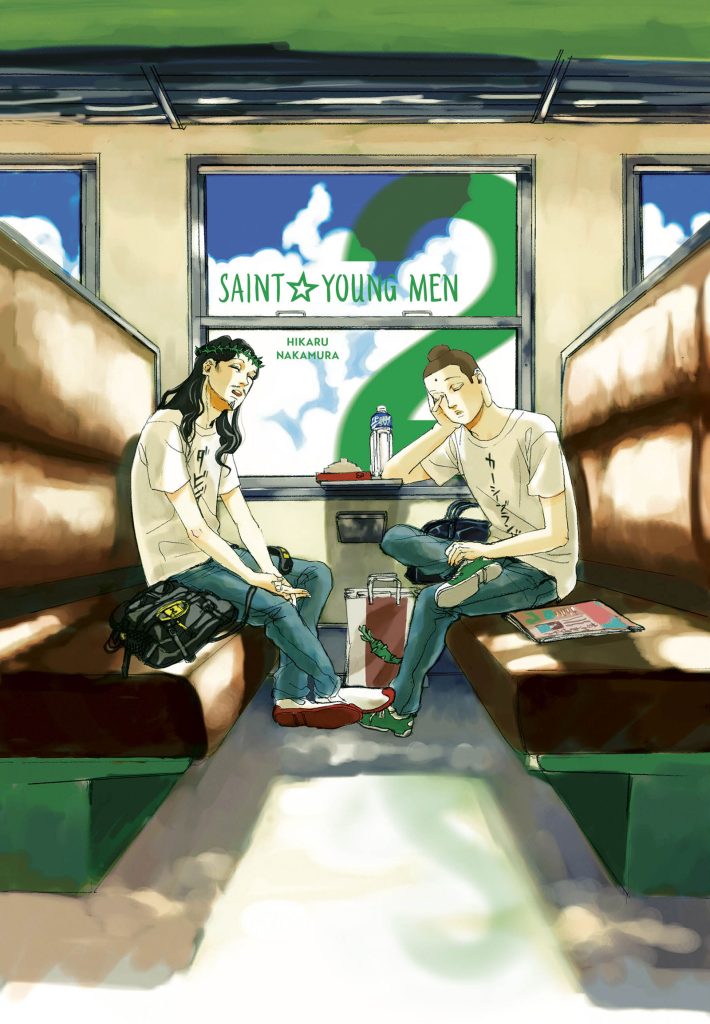

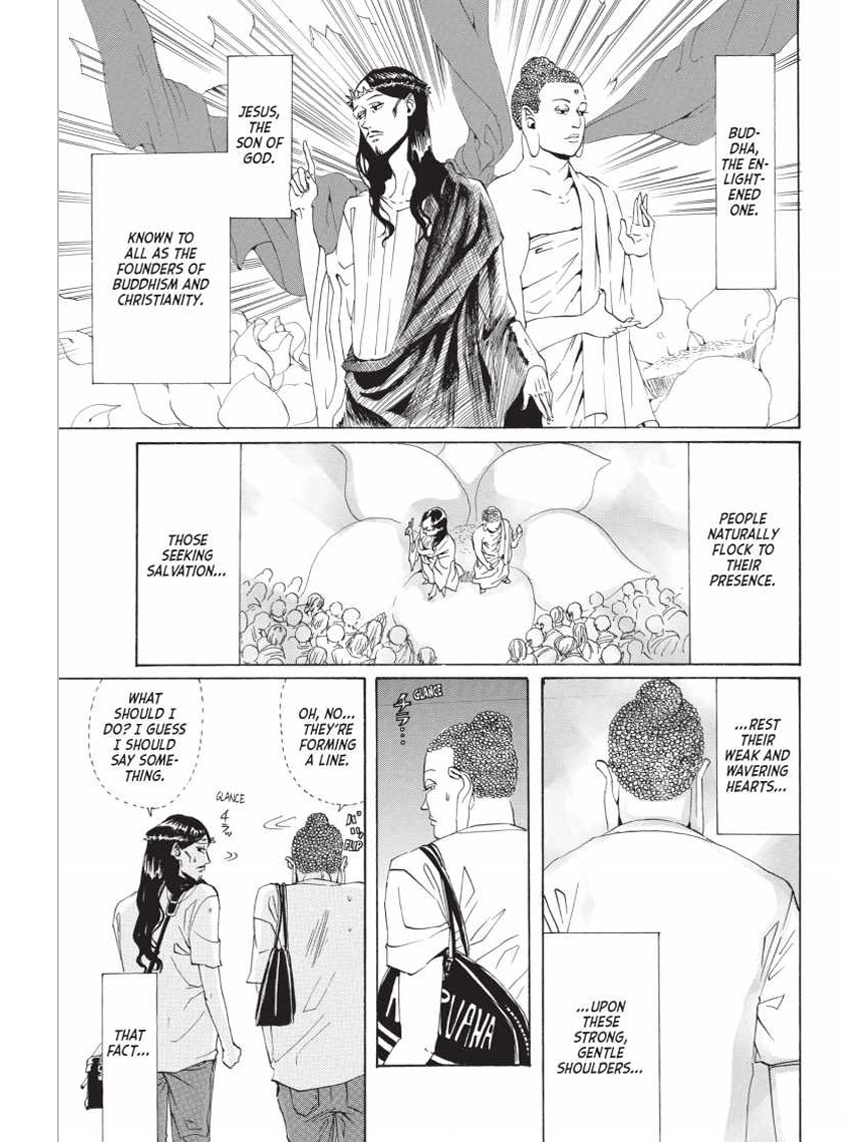

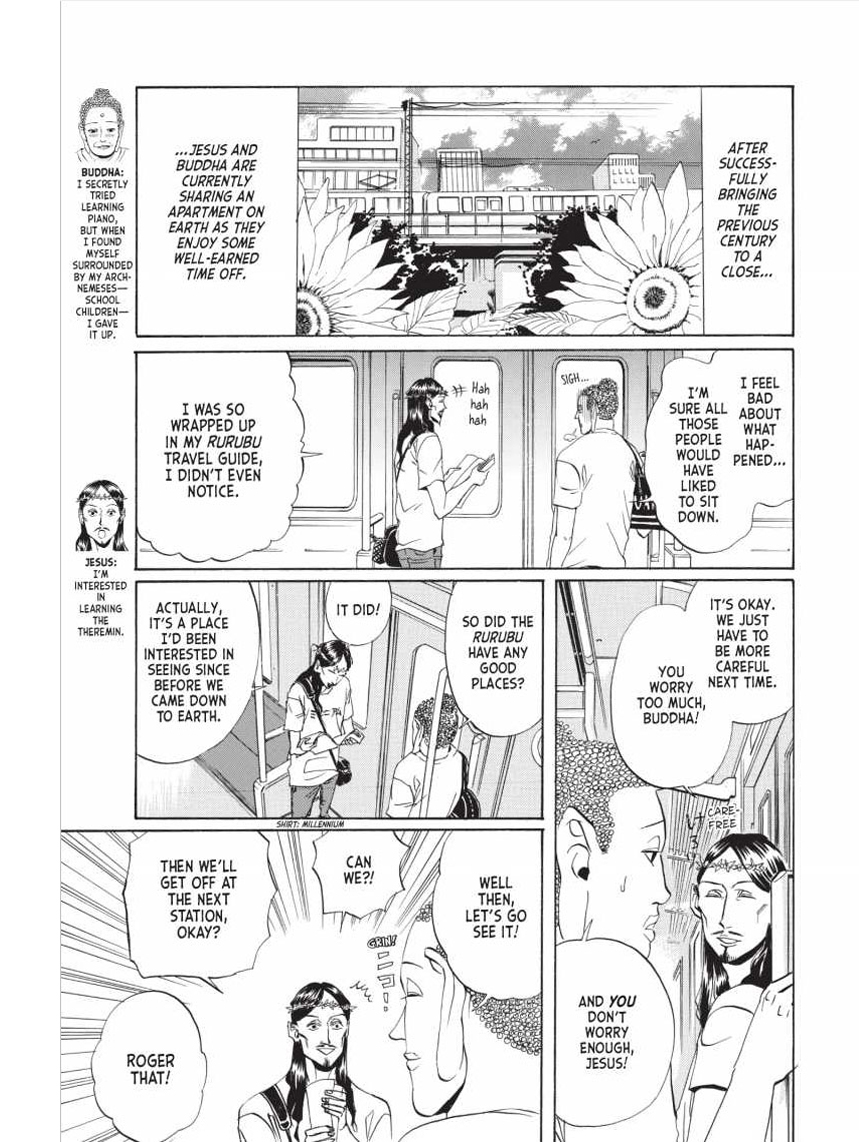

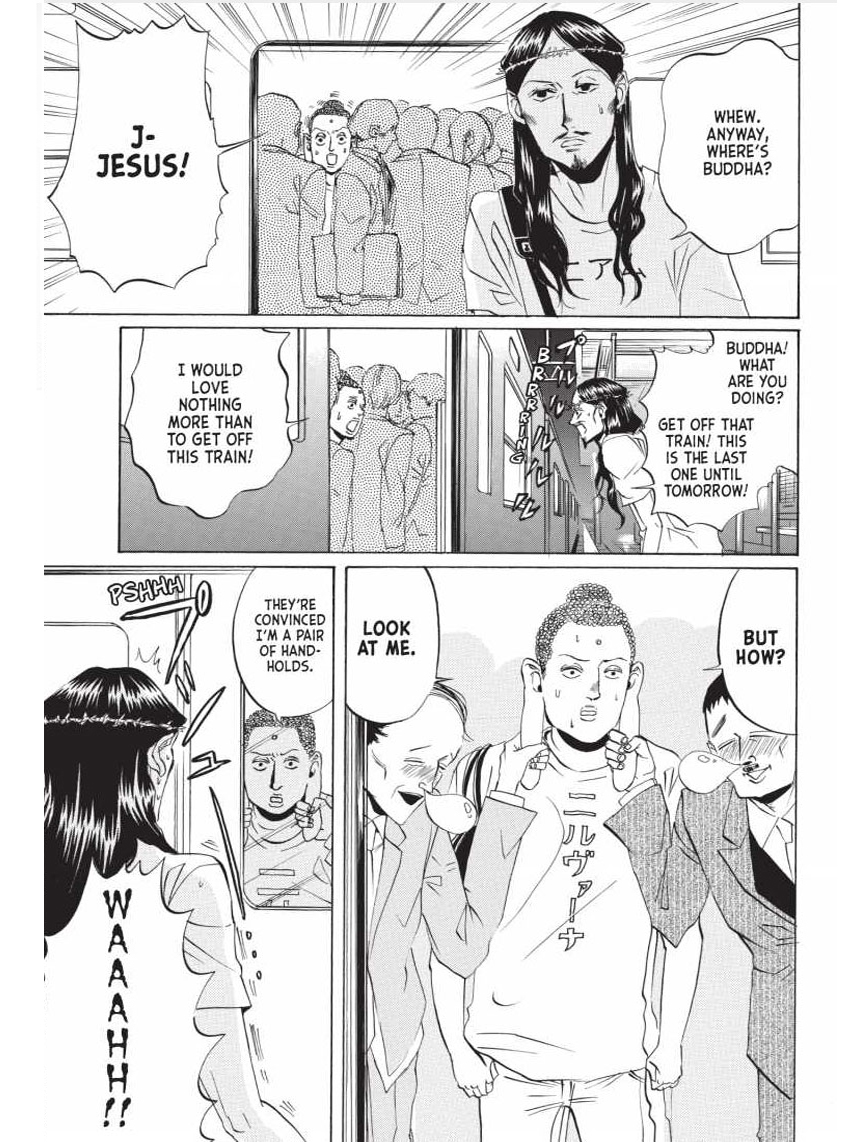

Pairing visual homage to classic artistic depictions of the Buddha’s parinirvana with a Japanese pun (hottoke means “scram!” while hotoke means “buddha”), these panels open Nakamura Hikaru’s rollicking comic Saint Young Men, a story about Jesus and the Buddha living as roommates in Tachikawa, a Tokyo suburb. After making it through the hectic turn of the millennium, the two decide to take a vacation from heaven. Their attempts to seamlessly blend into contemporary Japanese society come with decidedly mixed results. The two discover just how hard it is to assimilate—especially when Jesus inadvertently turns the water at the local public bath into wine, or when Buddha starts glowing auspiciously whenever somebody says something virtuous.

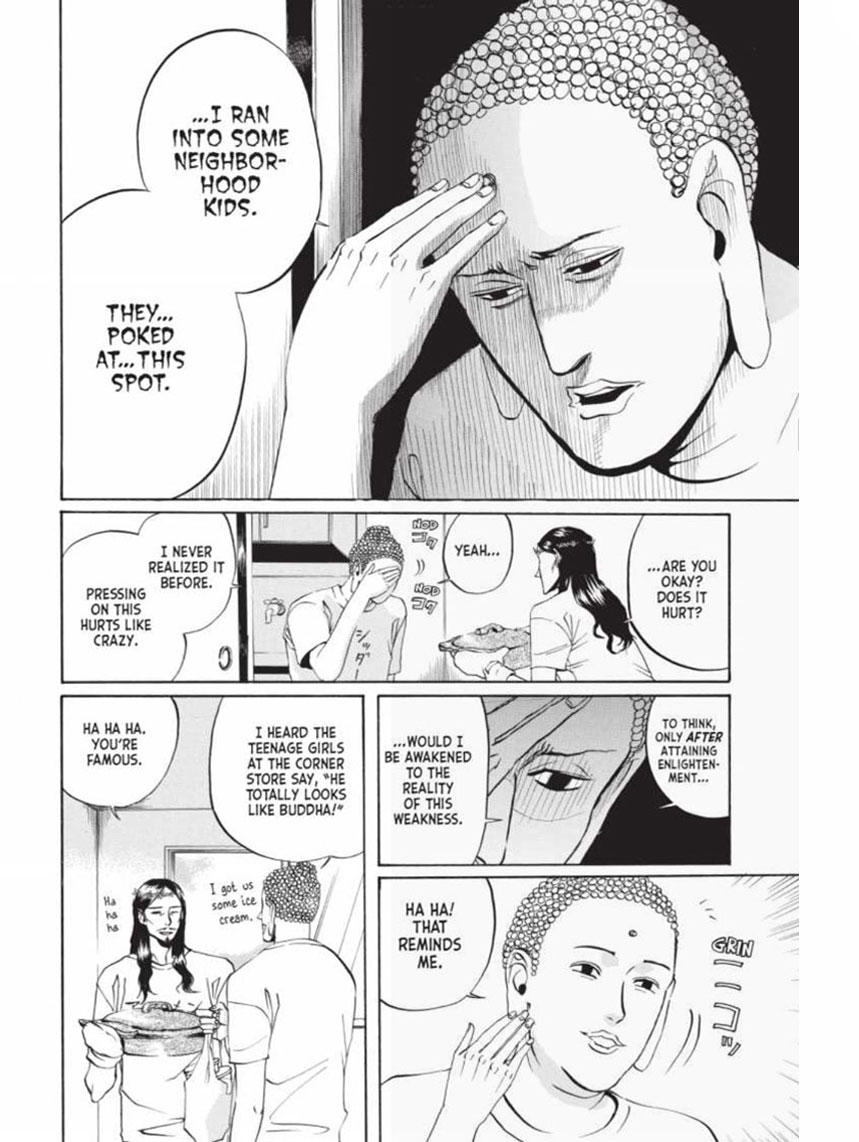

Now available in a new English translation from Kodansha Comics, this award-winning manga promises to capture the hearts of a broad international audience. Replete with puns, intertextual allusions, and cute asides in the extradiegetic spaces outside the panels and between chapters, Saint Young Men operates on multiple levels. Superficially, it is a slice-of-life story about two roommates with drastically different personalities. The two make a perfect odd couple: Jesus is a spendthrift while Buddha is parsimonious. Neighborhood girls swoon over Jesus’s resemblance to Johnny Depp, while schoolboys relentlessly flick the urna [auspicious mark] on Buddha’s forehead. Old folks piously present offerings to Buddha, while Jesus’s nasty scars convince local gangsters he is not to be messed with.

At another level, Nakamura’s juxtaposition of saintly figures with quotidian situations makes for outrageous scenarios that both reflect and disrupt common perceptions of religion in a country where it is widely perceived as stuffy and conservative. Even as the comic gently parodies religions, Saint Young Men also offers commentary on contemporary Japanese society, using the experiences of outsiders to reveal the tacit operations of peer pressure and shame, competition and cooperation, harmony and misunderstanding that structure Japanese daily life. Using Japan’s famed cycle of seasonal activities as a temporal backdrop for her tale, Nakamura humanizes two of the most famous religious founders in history while providing an underhanded intervention into commonsense cultural norms.

Nakamura and her publishers have repeatedly stressed that the manga is not intended to proselytize, but there’s no doubt that many clerics—and professors of religious studies—see Saint Young Men as a potential teaching tool. So what value might it have for teaching and learning about Buddhism?

To answer this question, I reached out to several colleagues who teach courses on Asian religions in Japan, the UK, Canada, and the United States to see how they planned to incorporate Saint Young Men in their classes. While many of these university instructors expressed excitement about the new translation, the general consensus was that Saint Young Men is better for teaching about the ambiguous position of religion in contemporary Japanese society than it is for teaching about Buddhism as such.

Bryan Lowe, an assistant professor of Religion at Princeton University, said that he planned to use the new translation in his course on religions in Japanese culture as part of a closing lesson on how religion is communicated in popular culture in Japan today. “[R]eligion. . .still plays a large role in Japanese social and cultural life, but it does so often outside of traditional religious institutions,” he wrote to me in an email. “While religiosity in Japan has always been diffuse, I’d say that it’s even more so today.…[T]exts like this allow us to see vibrancy outside of mainstream establishments and that there is still a market for religious discourse in contemporary Japan.”

At first glance Saint Young Men seems to share thematic similarities with the manga hagiographies of religious founders that populate Japanese bookstores and appear in temple souvenir shops. While these texts are not so well-known in the West, these popular introductions to Buddhism pair dramatic plots with adventurous pacing and stimulating imagery. Famous monks like Shinran, Saicho, and Kukai have all gotten the manga treatment, and prolific author Hiro Sachiya (a pseudonym) has produced a voluminous series of manga on buddhas and bodhisattvas such as Miroku (Sanskrit: Maitreya). Like all manga, they are not averse to using humor to transmit religious truths.

Nakamura’s series differs from these manga hagiographies and primers by eschewing didacticism in favor of telling an entertaining story. And although the series certainly rewards readers who are familiar with the life stories of Jesus and the Buddha, one does not need extensive background knowledge about either tradition to have a chuckle or even a hearty laugh.

Take one scene from the recently published first volume of the omnibus edition. Jesus and Buddha decide to attend the fall festival at the local Shinto shrine. After snacking on cotton candy and winning prizes at the the pop-up carnival stalls, the pair join the throng of people shouldering the portable shrine (mikoshi) just so that Jesus can wear a cool-looking overcoat called a happi, a cloth jacket traditionally worn during Japanese mikoshi rituals. (Jesus puns that wearing the happi makes him happy). Over Buddha’s protests that it might be unseemly, they end up wildly jostling the portable shrine and shouting along with the other festival-goers. Later they crack a beer under the shrine gate and watch fireworks. When Jesus and Buddha return home, they discover that the toys they won at the carnival stalls were cheap knock-offs: Buddha’s prize was not a portable game (a Nintendo DS Lite), but a flashlight (DS Light). Jesus got an eraser. Nakamura quips that the two had discovered the “true joy” (daigomi) of a Japanese festival, punning on a technical term for supreme Buddhist truth that can also colloquially mean the “true flavor” or “actual experience” of something.

As this example suggests, many of Nakamura’s jokes are quite challenging to translate. Her translators compensate by including explanatory notes between chapters and nestling glosses for technical terms in tiny font between panels. While Saint Young Men is hardly didactic, readers of the translation who are unfamiliar with Buddhism learn classic Buddhist terminology while being introduced to a cast of supporting characters such as Ananda, Rahula, and Sujata. Nakamura’s text therefore works as a sort of “expedient means” that naturally guides audiences to greater familiarity with Buddhist doctrine.

Erica Baffelli, Senior Lecturer of Japanese Studies at the University of Manchester, confirmed Dr. Lowe’s interpretation. When she teaches with the comic, she said, she highlights for students how religion is “othered” through the depiction of Jesus and Buddha as foreign guests in Japan, navigating the notoriously labyrinthine rules of social etiquette with more than a few faux pas. Although Dr. Baffelli was a bit skeptical about how useful the comic would be for introducing students to the doctrinal or historical specifics of Buddhism, she sees it as helpful for thinking about relationships between religion and media generally and religion and humor specifically, including discussions of what seems “safe” to parody. She noted, for example, that Saint Young Men offers a lighthearted take on Christianity and Buddhism, but never really addresses Islam, perhaps a pragmatic response to the 2005 Danish cartoon controversy.

Nakamura’s caution extends to the new translation, where some of the translators’ glosses actively reframe narrative content so as not to offend Nakamura’s expanded audience. For example, the concept of the Buddha drinking a beer is not particularly irreverent in Japan, since most Japanese Buddhist priests today eat meat, drink alcohol, and get married. (Priests even operate bars as a form of pastoral care.) Under such circumstances, having the Buddha crack a beer now and then seems perfectly reasonable. But in an interlinear gloss that does not appear in the original text, the translators stress for readers that Buddha’s beer is of course non-alcoholic.

I initially thought that sanitizing the manga in this way was excessively paranoid, but the translators’ caution is perhaps deserved. Daniel Friedrich, a lecturer at the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies and Hosei University, told me that when he introduced a group of visiting Thai students to Saint Young Men as part of a broader lesson on religion and media in Japan, many of the students were offended at what they saw as a sacrilegious portrayal of Buddhism.

If Nakamura studiously avoids slandering religion, she is also cautious when it comes to depicting religion as too serious. This delicate balancing act avoids another pitfall in Japan, where many laypeople perceive formal religious institutions as overzealous. Matthew McMullen, an associate professor at Nanzan University, suggested to me that it is precisely because Jesus and Buddha aimlessly kick around Tachikawa without having any particular goals in mind that Nakamura’s text avoids appearing pedantic or proselytizing. Nakamura herself draws an explicit distinction between “religion just for fun” and “religion taken too far.” In one scene, Buddha rushes to hide a life-sized Buddhist statue (lovingly nicknamed “Jr.”) from the landlord when she drops by unannounced because he fears it might give her the impression that he is a member of some “freaky religious organization” or “an extreme narcissist.”

For college students in both Japan and North America, generic conventions also affect their interpretations. Daigengna Duoer, a doctoral candidate at the University of California, Santa Barbara, told me that many of her students see homoerotic tensions in Nakamura’s plot. For them, Jesus fills the seme (aggressive, top) and Buddha the uke (passive, bottom) roles characteristic of the boys’ love (BL) manga genre, which typically features same-sex relationships between attractive male characters. While Nakamura may not have intended to give this impression, the students nonetheless found it enlightening to read the comic through this lens.

Ms. Duoer suggested that while Saint Young Men easily reinforces general stereotypes about religions through its depictions of famous founders, it can also disrupt prevailing notions of Buddhism as rigid, ascetic, and stoic. But there is a pitfall in the university classroom, she said, because instructors’ attempts to capture student interest through references to manga and sensational temple outreach programs such as animated music videos and android bodhisattvas can detract from students really engaging with the less scintillating aspects of Buddhist practice. Ultimately, instructors must think about why they want to mobilize such unconventional sources and what lessons these sources really teach.

Saint Young Men is an uproarious read. For those who are familiar with Buddhism, the new translation offers a lighthearted look at a tradition that often has a hard time laughing at itself. But whether the manga counts as a successful expedient means for introducing new audiences to Buddhism remains an open question.

♦

Jolyon Baraka Thomas authored the foreword to the second omnibus edition of Saint Young Men, released on March 17, 2020.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.