Vajrayana

Vajrayana Buddhism is a form of Mahayana Buddhism that developed in India and later spread throughout Buddhist Asia. Centering on mantra recitation, visualization, and complex rituals, Vajrayana—or “diamond vehicle”—methods use all aspects of experience as part of the path to awakening. Vajrayana teachings emphasize the importance of receiving guidance from a qualified teacher and often require initiation before a student can begin certain practices. While some elements of Vajrayana practice may seem unusual to the uninitiated, its teachings have been preserved and adapted in many Buddhist cultures, especially in East and Central Asia, and remain a living part of Buddhist practice today.

Table of contents

The Emergence and Spread of Vajrayana

The Vajrayana did not emerge in isolation. Many of its core ideas, such as a gradual path and mantras, were already emphasized in Mahayana Buddhism. However, new threads of Vajrayana thought and practices emphasized the guru, esoteric initiations, and rituals as means of rapid transformation. Coalescing as a distinct path around 700 CE, Vajrayana was at the forefront of Buddhist philosophy and practice in India for nearly 500 years. Though Buddhist institutions declined in India by the end of the 12th century, Vajrayana teachings had already taken root in numerous other places in Asia.

In East Asia, Vajrayana blended with Daoist and Confucian traditions, giving rise to “esoteric Buddhism.” In Japan, the Shingon and Tendai esoteric schools still preserve Vajrayana elements. Vajrayana also spread from India throughout the Himalayan regions of modern-day Nepal, Bhutan, and Sikkim. Indian tantric scriptures played a significant role in the formation of Tibetan traditions, particularly from the late 10th to the 13th centuries. Vajrayana practices were assimilated with preexisting beliefs and rituals, resulting in the distinctive forms of Tibetan Buddhism that exist today. As Vajrayana flourished in Tibet, it became the dominant form of Buddhism in the region, with monastic institutions preserving and refining its practices. Tibetan lamas later played a crucial role in spreading and popularizing Vajrayana, bringing its teachings to Mongolia, China, and parts of Russia.

Beyond religious institutions, Vajrayana also influenced art, literature, and meditation across Asia, shaping ritual aesthetics, sacred texts, and visualization-based contemplative practices. Over time, Vajrayana practices and teachings were incorporated into Buddhist practice in the West. Some contemporary Buddhist leaders seek to modernize Vajrayana systems, adapting them to new cultural contexts, while others work to maintain and protect traditional approaches. Despite these evolving interpretations, Vajrayana’s distinct methods continue to inspire practitioners worldwide.

Vajrayana Scripture or Buddhist Tantra

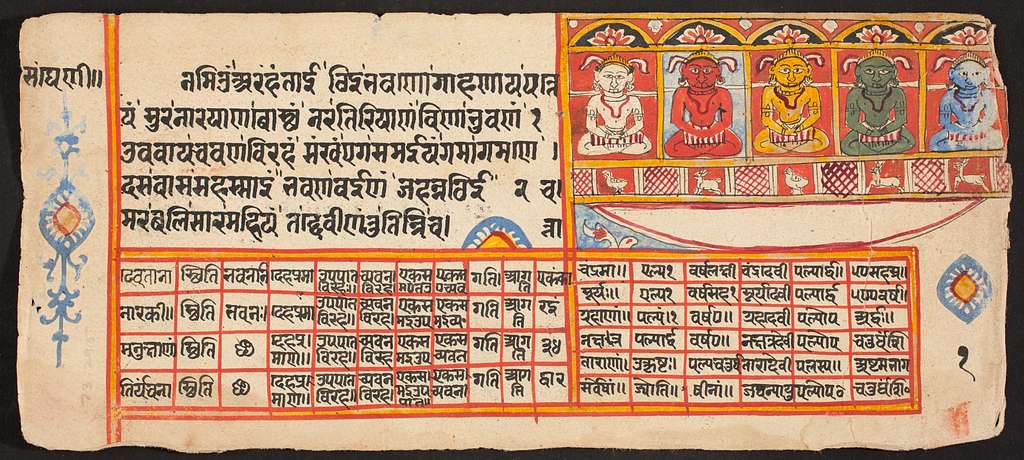

Vajrayana scriptures, known as tantras, drew upon themes found in earlier Mahayana texts, particularly the dharani sutras and the Perfection of Wisdom (Skt.: prajnaparamita) literature. The tantric scriptures emphasized the power of mantras—sacred words, syllables, or phrases used to invoke a deity or accomplish other aims. Unlike earlier Buddhist sutras, the tantras highlight the efficacy of esoteric rituals, visualization techniques, and symbolic language designed for initiates who are practicing under the guidance of a guru. Most Vajrayana scriptures, originally written in Sanskrit and lesser-known languages such as Apabhramsa, are from India. Many were later translated across the Buddhist world, especially in Tibet.

Tantric texts are traditionally classified according to the types of practices they promote. Action tantras (kriyatantra) describe rituals that focus on external objects, such as a statue or a painting of a buddha or deity. Yoga tantras (yogatantra) shift the emphasis inward, guiding practitioners to visualize themselves as an enlightened being. Between the 8th and 10th centuries, new genres of texts, including the Mahayoga and Yogini tantras, emerged. Texts such as the Guhyasamaja Tantra, Guhyagarbha Tantra, Cakrasamvara Tantra, and Hevajra Tantra introduced coded language to describe advanced practices, including sexual yogas, charnel ground meditation, venerating wrathful deities, consuming meat, and drinking alcohol, among other monastically transgressive themes. Tantras sometimes encourage behaviors such as lying, stealing, and actions that contradict mainstream Buddhist ethical guidelines, emphasizing the willingness of tantric practitioners to transgress all conventional concepts in the pursuit of enlightenment.

The tantras were the primary scriptural authority in Vajrayana traditions, but practitioners more commonly followed ritual handbooks known as sadhanas, which provided step-by-step instructions for daily practice. These texts evolved over time, reflecting changes in ritual traditions. Manuscripts found in the Dunhuang Caves, for example, contain handwritten notes where practitioners modified ritual sequences or added personalized instructions. Such materials offer scholars valuable insights into the development and adaptation of tantric Buddhism throughout the centuries.

The Guru

Buddhist teachers have always been highly respected, but in Vajrayana, the guru is regarded as the key to the tantric path—an enlightened being who confers esoteric teachings and initiations. Seeing the guru as a buddha is central to Vajrayana practice, and students are expected to receive teachings with complete devotion. Without the guru’s guidance, one cannot properly engage in tantric practices.

Early Vajrayana communities in India often revolved around lay gurus, who, although not bound by monastic ordination, were regarded as highly accomplished practitioners. These figures, sometimes regarded as siddhas for their supernatural abilities, were often criticized by monastics for ignoring ethical norms while making grandiose claims to enlightenment. As tantric practices were integrated into monastic institutions, the role of the guru was increasingly formalized, blending elements of both monastic and lay traditions.

The first tantric vow, or samaya, is never to disparage one’s guru. Instead, disciples are expected to serve the guru in thought and action, use honorific speech, and follow their instructions. Much of the preliminary training for tantric disciples focuses on cultivating proper conduct toward the guru, as outlined in a 10th-century handbook called Fifty Verses on the Guru.

Over the centuries, different types of gurus have emerged within the Vajrayana. In Tibetan Buddhism, monastic gurus often hold institutional leadership, while tulkus, or reincarnated teachers, serve as revered gurus or lamas and have held positions of political power. Lay gurus remain influential, particularly in Nepalese, Tibetan, and Japanese traditions. While female gurus have historically been less common, women have played a significant role in Vajrayana lineages, with some recognized as great teachers and practitioners.

Disciples engage in practices with the understanding that the guru embodies the enlightened mind and is an object of devotion and reverence. This relationship is considered foundational and makes the guru indispensable for practitioners on the path.

Stages of the Vajrayana Path

Vajrayana practitioners follow a structured path that begins with preliminary practices and continues toward advanced tantric techniques. Throughout this process, rituals play an important role in generating merit, cultivating the mind, and transforming one’s perception. Daily sadhana (practice) often includes making offerings, reciting mantras, visualizing deities, and supplicating the guru. More elaborate communal rituals, such as feast offerings (Skt.: ganachakra; Tib.: tsok), are performed on auspicious days.

The path begins with preliminary practices (purascarana; ngondro), which purify karma, establish the proper mindset, and help the practitioner gather momentum for the start of the long, disciplined journey. Preliminary practices vary by tradition but often involve reciting tens of thousands of mantras, prostrations, and other acts of devotion. In Indian Vajrayana, preliminaries commonly included veneration of buddhas and bodhisattvas, while guru yoga—a practice of visualizing and merging with the guru’s enlightened mind—became central in Tibetan traditions. Japanese Shingon Buddhism, by contrast, emphasizes fire offerings (Skt.: homa) as a preliminary ritual.

After completing the preliminaries, students receive tantric initiation from a qualified guru. The core practice for Indian Vajrayana is deity yoga, in which practitioners visualize themselves as enlightened beings while reciting a corresponding mantra. This practice trains the mind to perceive reality as inherently pure, using buddhahood as the basis of the path, a defining feature of Vajrayana, which is also called the “path of the fruit” or the “resultant vehicle” (Skt.: phalayana; Tib.: bras bu theg pa).

Unlike many earlier Buddhist models, which emphasize gradual progress over countless lifetimes and eons, Vajrayana promises the possibility of enlightenment in this very lifetime. Tantric techniques incorporate advanced visualization, breathing techniques, and yogic practices to accelerate realization. In the final stage of deity yoga, the visualization dissolves into emptiness, allowing the practitioner to rest in nondual awareness. Some traditions, such as Mahamudra (Great Seal) and Dzogchen (Great Perfection), emphasize direct realization of the mind’s luminous nature as the culmination of the path.

Tantric Initiation and Transmission

Vajrayana developed as an esoteric tradition, in which initiations (Skt.: abhiseka) were required to access tantric teachings. These initiations, performed by a guru, serve as ritual transmissions that empower a practitioner to engage in specific practices. The Vase initiation, one of the earliest forms, purifies the body and senses through sprinkling water from a ritual vessel. Later systems retained this rite at the beginning of the initiation ritual. Once receiving tantric initiations, disciples are expected to follow the principal fourteen tantric vows.

Vajrayana included sexual initiations, in which practitioners engaged in sexual yoga with a consort and consumed bodily fluids as sacred substances. These practices, which appeared in texts such as the Hevajra Tantra, were considered highly transgressive within medieval Indian society and Buddhist monastic codes. As Vajrayana spread into monastic institutions, these rituals were often adapted into symbolic or visualization-based practices, particularly in Tibetan traditions.

The tantras, which serve as the scriptural basis for initiation rituals, are traditionally attributed to the Buddha, even though most were composed between the 7th and 11th centuries. By presenting the tantras as direct teachings of the Sakyamuni Buddha, Vajrayana texts established lineage authority, ensuring the continuity of transmission. The guru, as the living representative of this lineage, plays a central role in interpreting the symbolic and coded language used in tantric scriptures.

Transmission in Vajrayana is more than studying the texts—it involves direct instruction and oral transmission (agama), ensuring that teachings are correctly understood and practiced. Receiving a tantra is not only an intellectual process but also an experiential initiation, deepened through repeated recitation, visualization, and ritual performance under the guidance of the guru.

As Vajrayana developed, Indian monastics compiled standardized initiation sequences that could be used for different situations. While sexual yogas remained central in certain traditions, many monastic settings framed them as purely visualization-based to align with Mahayana ethical principles (although some argued that these yogas did not break the monastic vows if they were performed without desire). The domestication of Vajrayana enabled it to take root in Buddhist monasteries, striking a balance between esoteric practices and traditional Buddhist morality.

Despite various adaptations over the centuries, tantric initiation remains an important method for transmitting Vajrayana practices and esoteric wisdom to new generations.

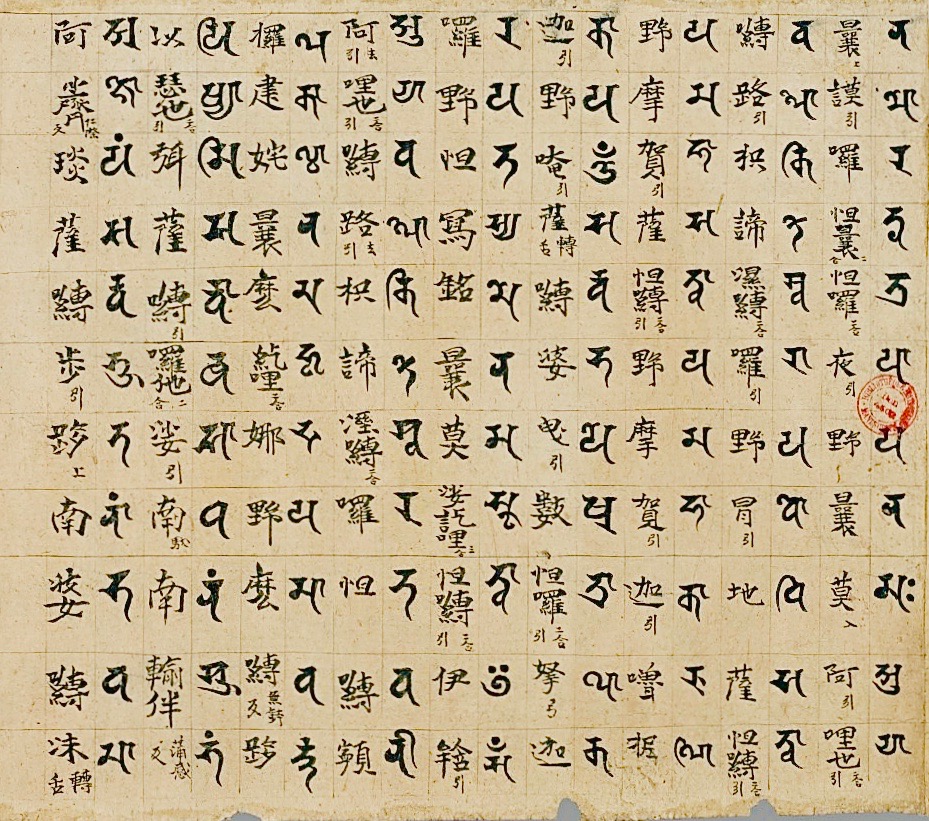

Mantras and Dharanis

In Vajrayana practice, mantras and dharanis are sacred sounds, syllables, or phrases used as powerful tools to transform the mind. Rooted in ancient Indian Vedic texts, they predate Buddhism and were later integrated into Mahayana and Vajrayana practice. While both of these Sanskrit terms have been translated as “spell,” “charm,” and “magic formula,” they are more than just magical invocations, serving as focal points for meditation and awakening in both ritual contexts and day-to-day life. Another name for Vajrayana is Mantrayana, also known as the mantra vehicle.

Although similar in function to dharanis, mantras are generally shorter and often lack direct semantic meaning. Their power is believed to come not from their literal translation but from the act of reciting them, which invokes the presence of a deity, purifies the mind, and generates merit. Dharanis, on the other hand, are usually longer, appearing in Mahayana sutras and early tantras. Mantra and dharani phrases can serve as a mnemonic device that captures the meaning of a much longer text, as, for example, the final mantra at the end of the Heart Sutra:

Gate gate paragate parasamgate bodhi svaha :

“gone, gone, gone beyond, fully gone beyond, awake, so be it!”

The role of mantra became increasingly central as Vajrayana developed into a distinct Buddhist path. In tantric rituals, mantras are used for purification, invocation of a deity, and consecration, aligning the practitioner’s mind with the enlightened qualities of a buddha or bodhisattva. For instance, the well-known mantra Om Mani Padme Hum is associated with Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion, while the Hundred-Syllable Mantra of Vajrasattva is recited for purification. Mantras are also used to bestow blessings, secure protection, and remove obstacles.

Beyond ritual contexts, reciting mantras is a central practice in Vajrayana daily life. Whether chanted aloud, whispered, or silently repeated, mantra recitation focuses the mind, calms emotions, cultivates awareness, and offers a way to accumulate merit. The repetitive nature of the practice helps transcend conceptual thought and can bring the practitioner to deeper states of meditation and clarity. Through both formal ritual and personal devotion, mantras and dharanis remain an essential element of Vajrayana practice, serving as links to the enlightened mind of the deity.

Deity Yoga

Deity yoga is the core practice of Vajrayana Buddhism, providing a method for practitioners to cultivate the enlightened qualities of a buddha. Unlike earlier Buddhist traditions, which primarily view deities as external figures to venerate, Vajrayana introduces visualization techniques that enable practitioners to identify with a deity, embodying their wisdom and compassion.

In action tantras (Skt.: kriyatantra), deities are invited into a ritual space and honored with offerings, similar to traditional devotional practices. The deity is treated as an honored guest who, in turn, bestows blessings on the practitioner. As Vajrayana traditions developed, ritual elements became more internalized, leading to the practice of self-generation, where the practitioner visualizes themselves as a deity, known as yoga tantra (yogatantra), rather than engaging with an external presence, whether a dancing female dakini or the ferocious form of a wrathful buddha.

Deity yoga consists of two states: generation (utpattikrama) and completion (nispannakrama). In the generation stage, the practitioner uses visualization and mantra recitation to invoke the deity. Vajrayana deities have distinct forms, expressions, and ritual implements, each carrying symbolic meaning. They arise from a seed syllable, an essential sound associated with their mantra. Through visualization, the practitioner dissolves the ordinary sense of self, identifying fully with the deity’s enlightened qualities.

In the completion stage, the visualization dissolves, allowing the practitioner to rest in the luminous nature of the mind. This phase represents the realization of emptiness, the understanding that both the deity and the practitioner’s identity are ultimately free from inherent existence. By transcending an ordinary sense of self, the practitioner cultivates “divine pride” (divyagarva)—a deep conviction in their own awakened nature—and perceives appearances as manifestations of enlightenment.

Deity yoga is a method for practitioners to gradually train, first by focusing on the recitation of mantra and visualizing the deity, and then by dissolving the visualization and relaxing the mind.

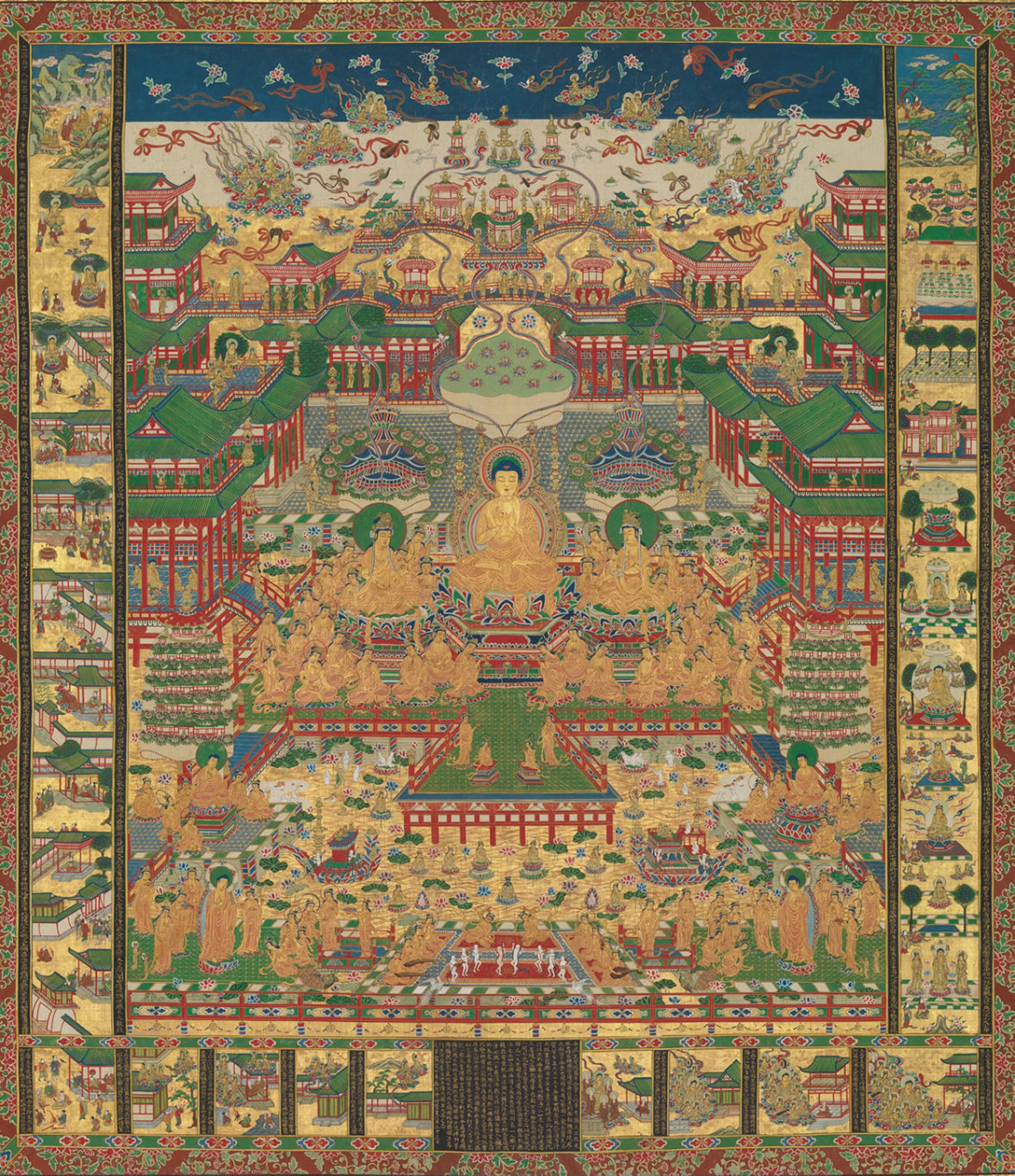

Visual Culture

Vajrayana Buddhism is rich in visual symbolism. Monasteries and temples are typically adorned with colorful paintings, intricate sculptures, and elaborate mandalas, or geometric diagrams, used in initiations and rituals. These artistic representations depict an array of mythological beings and enlightened buddhas, ranging from peaceful deities sitting on lotus flowers to wrathful protectors adorned with skull garlands and weapons. Much of this imagery can also be found on home shrines.

Each element of a deity’s appearance carries symbolic meaning. For example, the vajra and bell, hand-held instruments that are used in nearly every Vajrayana ritual, represent the unity of appearance and emptiness, while weapons with sharp blades symbolize cutting through delusion. Many deities stand upon defeated figures, representing the subjugation of ignorance and negative emotions. Hand gestures (Skt.: mudras) represent different aspects of enlightenment, such as fearlessness, or indicate deep meditative concentration. Practitioners use these images as guides for discipline and transformation, mirroring the postures and attributes of deities while performing rituals.

The Vajrayana pantheon is arranged hierarchically in mandalas, which visually represent enlightened realms and temple structures. In paintings, sculptures, and temple murals, deities are positioned according to their function. Protectors, gatekeepers, dakinis, and other beings often surround a central buddha or bodhisattva. These mandalas may be painted on cloth thangkas, on monastery walls, or constructed three-dimensionally in temple complexes and pilgrimage sites.

Tibetan sand mandalas are carefully created with colored sand and then ritually destroyed, symbolizing the impermanence of all phenomena. Beyond mandalas, visual imagery plays an important role in deity yoga, where practitioners meditate on depictions of enlightened beings during practice, rituals, and initiations. Statues and portraits of gurus and sacred relics also serve as devotional objects, reinforcing the link between the practitioner and their lineage of masters and offering a source of inspiration and blessings.

Vajrayana in East Asia

As Vajrayana Buddhism spread beyond India, it merged with local religious and philosophical traditions, as well as other forms of Buddhism. In China, Vajrayana teachings blended with Daoist and Confucian practices, giving rise to “esoteric Buddhism” or “esoteric teaching” (Ch.: mizong; mijiao). Indian Buddhist monks such as Amoghavajra, Subhakarasimha, and Vajrabodhi arrived in China via the Silk Road and along southeastern maritime trade routes, translating early tantras and establishing what came to be known as the mantra school (zhenyan) during the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE). These teachings introduced new ritual aspects originating from India, including mandalas, mantras, tantric initiations, and deity yoga, which were then incorporated into preexisting Chinese Buddhist traditions. The veneration of esoteric deities, such as Vajrapani and Avalokiteshvara, became widespread, with Avalokiteshvara later evolving into the female bodhisattva Guanyin.

The fortunes of esoteric Buddhism in China fluctuated with the political climate. While Emperor Daizong (r. 762–779) was a devoted patron of Vajrayana Buddhism, Emperor Wuzong (r. 840–846) initiated a large-scale persecution of Buddhism, which led to the decline of state-supported esoteric schools. Despite these vicissitudes, Vajrayana teachings continued to influence Buddhist traditions throughout East Asia.

During this time, the Indian monk Amoghavajra taught pilgrims from Korea and Japan, and his disciple Huiguo (746–805) instructed Kukai (774–835), whose disciples later founded the Shingon school in Japan. Shingon, which emphasizes the Mahavairocana and Vajrasekhara sutras, remains a vital esoteric Buddhist tradition in Japan today. Another esoteric Chinese tradition, Tiantai, became influential in Japan as Tendai, incorporating elements of Vajrayana into its teachings. Vajrayana practices also became popular in Korea, and, by the 10th century, had formed the influential Cheontae school. This school was eventually absorbed into the Seon meditation tradition of the dominant Chogye order. A modern revival of an independent Cheontae order was founded in 1966 and currently has a few million followers. Vajrayana teachings also influenced local Buddhist traditions in Vietnam.

Despite regional differences, Vajrayana Buddhism in East Asia formalized preliminary practices and esoteric methods, guiding practitioners toward union with the body, speech, and mind of the Buddha.

Tibetan Buddhism

The main transmission of Vajrayana Buddhism to Tibet coincided with a period of significant developments in India during the 10th and 11th centuries. Tibetan rulers and scholars sought the latest and most highly prized tantric teachings from India, inviting esteemed Buddhist teachers from India while also sending translators and monks to study at Indian monastic universities. As a result, new Mahayoga and Anuttarayoga tantras entered Tibet, shaping its unique form of Vajrayana Buddhism.

During this time, prominent teachers introduced distinct Vajrayana lineages to Tibet. Drogmi Lotsawa (c. 992–1064) established the Path and Fruit (Tib.: Lamdre) teachings, which became central in the Sakya school. Marpa the Translator (1012-1097) traveled to India multiple times, transmitting teachings that formed the foundation of the Kagyu school. Tibetan historians refer to this period as the new translation era (Tib.: sarma) in contrast to the earlier Buddhist transmission that occurred during the Tibetan Empire.

By the 13th century, Buddhism had largely disappeared from its Indian homeland due to invasions, competition from other religious traditions, and the decline of institutional support. Tibetan monastic centers preserved and further developed Vajrayana practices; however, Tibetan Buddhism is not identical to Indian Vajrayana, although this is sometimes mistakenly assumed to be the case. Over time, Tibetan Buddhism incorporated elements of indigenous ritual traditions, as well as meditation techniques from China, creating a unique Tibetan form of Buddhism.

Tibet became a major center of Vajrayana, influencing surrounding regions such as Mongolia, Bhutan, Nepal, and parts of Russia and India. Tibetan lamas played essential roles in transmitting Buddhist teachings to Mongolian and Chinese rulers, including Kublai Khan (1215–1294). Today, Tibetan Buddhism remains the predominant form of Buddhism in the Himalayan region and continues to shape Buddhist practice worldwide.

Learn more about Tibetan Buddhism

Important Figures in Vajrayana

Vajrayana Buddhism was shaped by generations of scholars, gurus, and lineage holders whose teachings continue to define the tradition. Some were monastic philosophers who systematized complex tantric doctrines; others were wandering adepts who tested the limits of Buddhist norms and social conventions. Together, these figures transmitted Vajrayana teachings to subsequent generations, laying the foundation for the traditions we see today.

Several early scholar-monks played a key role in formalizing Vajrayana ritual and doctrine. Buddhaguhya (c. 700) wrote a foundational commentary on the Mahavairocana Tantra and helped transmit tantric teachings to Tibet. Buddhajnanapada (c. 770–820) was a leading interpreter of the Guhyasamaja Tantra. Abhayakaragupta (11th century) systematized initiation rites in his Vajravali, and Ratnakarasanti (10th–11th century) synthesized Yogacara and Madhyamaka thought in tantric contexts. Their writings helped establish the intellectual and ritual structure of Indian Vajrayana Buddhism.

The mahasiddhas were wandering tantric adepts renowned for their unconventional lifestyles and radical methods. Saraha (c. 10th century) expressed Vajrayana insights in mystical songs and is remembered as a forerunner of Mahamudra traditions in Tibet. Tilopa (988–1069) passed on essential oral instructions, including the “six nails,” to his student Naropa (c. 10th–11th century), a former monk who undertook intense training. Maitripa (1007–1085), known for teaching nonconceptual meditation, renounced his vows to pursue a direct approach to realization. Naropa’s teachings were brought to Tibet by Marpa, the guru of Milarepa, whose life of solitary retreat and song became a model of tantric realization.

Other figures are remembered for transmitting tantric teachings across regions and founding influential lineages. Atisa Dipamkara Srijnana (982–1054) traveled from India to Indonesia, and later to Tibet, where he became central to the Kadampa and later Geluk traditions. Sri Simha, Jnanasutra, and Vimalamitra (8th–9th century) formed a lineage of meditation masters associated with the Dzogchen tradition. Niguma (10th–11th century), a female tantric adept, transmitted the teachings known as the Six Yogas of Niguma, foundational to the Tibetan Shangpa Kagyu tradition.

While the historical details of these teachers vary, their continued presence in Vajrayana practice is undeniable. Their words are chanted in rituals, their visions preserved in mandalas and lineages, and their teachings continue to guide practitioners. Rather than historic icons of a distant past, these teachers remain active participants in the tradition, transmitted through memory, texts, practices, and devotion in both monasteries and homes around the world.

Buddhism for Beginners is a free resource from the Tricycle Foundation, created for those new to Buddhism. Made possible by the generous support of the Tricycle community, this offering presents the vast world of Buddhist thought, practice, and history in an accessible manner—fulfilling our mission to make the Buddha’s teaching widely available. We value your feedback! Share your thoughts with us at feedback@tricycle.org.